Loading component...

At a glance

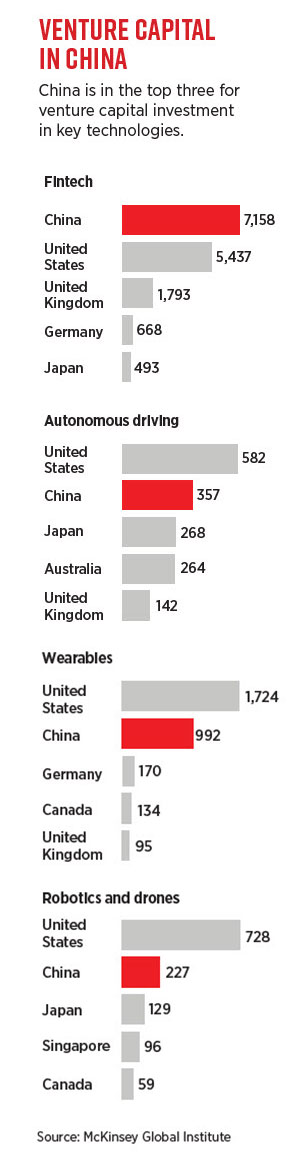

- China is among the top three countries for venture capital in key technologies.

- New research on more than 200 Chinese companies identifies three sets of innovators: hidden champions, tech underdogs, and change makers.

- Each category represents different types of challenges for competitors.

Chinese giants such as Haier, Tencent, Baidu and Alibaba are now counted as global players, welding technological innovation to marketing know-how and entrepreneurial drive.

However, the size and rapid growth of these pioneers can obscure the emergence of thousands of smaller companies developing in China’s commercial hothouse. They are supported by a dynamic venture capital sector and an expanding domestic market.

New research shows that all of them look, or will soon look, to overseas markets, and many of them are successfully competing against multinational firms operating in China.

“This new generation is looking beyond boundaries and cultivating a disruptive mindset,” says Mark Greeven, professor of innovation and strategy at IMD Business School in Lausanne, and one of the authors of a comprehensive study into Chinese business innovators.

“If one Alibaba can shock international stock markets and disrupt traditional industries, we can only imagine what tens of thousands of under the radar tech-based entrepreneurs will do.”

To see the ground-level picture, Greeven and his colleagues interviewed hundreds of executives, entrepreneurs and investors in China, and studied more than 200 companies.

Beyond the established giants, they identified three sets of Chinese innovators: hidden champions, tech underdogs and change makers. Each represents a different set of challenges for competitors.

Hidden Chinese innovation champions

Usually, hidden champions are mid-size innovators in niche markets. Greeven classifies these as recording annual revenue of less than US$5 billion.

Their strategy is based on long-term growth driven by investments in R&D to expand within their niche or into closely related areas.

The research identified more than 200 hidden champions in sectors ranging from machinery and chemicals to materials and electronics.

A company that typifies this group is Hikvision, which was launched in 2002 with an innovative video compressor card for computers based on MPEG4 technology. It has followed up with a stream of products in the field, often releasing several new products or upgrades in a year.

Nearly half of the company’s employees work in R&D, and about 8 per cent of revenues are invested in the area.

The company began a global expansion program several years ago, and is already a leading player in this field of technology.

It has developed partnerships with Western companies, to the point that half of its revenues now come from outside China.

“A surprising feature is how quickly hidden champions can grow,” Greeven says.

“Many became domestic and global market leaders in about a decade. It is dangerous for multinational companies to underestimate the speed and flexibility with which these new competitors can emerge, make decisions and expand.”

China's change makers

While hidden champions seek to dominate an industry niche, change makers aim for the mass market, seeking benefits from digital disruption and often taking advantage of China’s high level of mobile internet use.

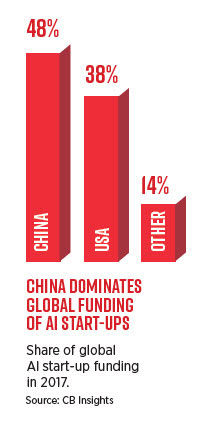

These companies are able to find start-up funding from China’s large venture capital market.

Toutiao, a media platform that uses artificial intelligence (AI) to provide customised news through mobile phones, was supported by more than US$3 billion in venture capital after it was founded in 2012.

In July 2018, it had more than 120 million daily active users and was valued at more than US$11 billion.

There is no shortage of young people wanting to start a digital business in China, whether in media and information, ride-hailing, finance or retail.

Greeven notes that the online foodordering service Ele.me was founded in 2008 by two students from Shanghai Jiao Tong University who, the story goes, got hungry while playing video games one night. By 2015, the company’s revenue had passed US$1 billion.

An outstanding feature of this group is that it shapes digital technology to fit consumer demand, not the other way around.

Its success, especially among younger demographics, has meant that all business-to-consumer companies operating in China are now expected to have on-demand and mobile capacities.

“These companies can come out of nowhere, continually engaging with users through social media to adapt products and, as necessary, revamp their business models,” explains Greeven.

“Unlike corporations with legacy products and business models to maintain, change makers are entirely user-centred.

"Rather than pushing an existing product line, they are willing to venture beyond the industry’s boundaries if they see opportunities there.”

Tech underdogs

The third category, tech underdogs, are small and mid-size enterprises, usually science or technology-based, with revenue of less than US$60 million. Greeven and his colleagues identified tens of thousands of these across a wide range of emerging-tech fields. The research identified more than 150 companies with significant intellectual property in photovoltaic technology, for example, and 80 healthcare ventures utilising various forms of AI.

“Many of these companies were founded by people returning to China from overseas, having studied at elite universities in the US or Europe,” notes Greeven.

“Unlike innovators in Silicon Valley, Chinese entrepreneurs work collectively to innovate and push technology and market boundaries. Although many of the ventures do not survive, some become viable competitors and even market leaders. The large number of players in any given category in China increases the chances that at least one will be able to break through.”

There have been a number of cases of Chinese companies in this category partnering with Western firms as a growth strategy. One example is Weihua Solar collaborating with German chemical company Merck, with Merck agreeing to supply advanced materials and patented information to supplement Weihua Solar’s internal R&D efforts. This partnership eventually led to the development of a solar cell that is light, flexible and more efficient than any of its competitors.

However, tech underdogs have also proved to be entirely capable of developing advanced technology on their own. The companies are targeting increasingly sophisticated fields, including genetics, cloud technology, next-gen AI, and advanced materials. Royole, a Shenzhen-based start-up, is an innovator in super-thin screens and flexible displays, and has introduced the world’s first bendable smartphone, which can be folded like a wallet.

According to Greeven, for non-Chinese competitors the sheer number of ventures in this category is a problem, particularly as even successful ones have little media presence.

“It makes it difficult for multinationals to know which local companies represent a threat and which do not,” he says.

“Compared with their Chinese counterparts, multinationals based outside China tend to have fewer connections with local companies and investors.

As a result, they are not part of the conversation about emerging threats. For the tech underdogs, that lack of visibility can be an advantage that enables them to catch established competitors off-guard when entering new markets.”

Challenges ahead for China

While Chinese firms in each category have shown great capacity for innovation, the research suggests persistent structural weaknesses.

For the hidden champions, the danger is that they will themselves be subject to technological disruption. As they become more successful, their public profile will grow, prompting more competition. They are particularly aware of the possibility of new market entrants from India and South-East Asia leveraging their own large domestic markets as a springboard for regional and global markets.

The change makers face the problem of creating sustainable competitive advantage in a market of fast-moving trends. They are also aware that regulatory changes in China could undercut their business model, and that regulatory systems in other countries could impede expansion.

For the tech underdogs, there is the problem of commercialising niche technology. Because so much is invested in a single product, failure to launch means there are few, if any, alternatives.

CPA Australia Library resource:

Ways to compete in China

Mark Greeven and his colleagues have a series of recommendations for companies wanting to compete in China or that are concerned about Chinese competition at home.

1. Expect the unexpected.

A Western company might be aware of its main Chinese competitors, but there are likely to be others who are keeping a low profile or have not yet made the decision to go global.

A good move is to improve knowledge of industry developments within China to include threats that are not immediately obvious, and to assess their strengths and weaknesses.

2. Look for collaborative opportunities.

Many Western companies have built good partnerships with Chinese firms, usually through subsidiaries. Those companies that have been willing to give Chinese subsidiaries more local autonomy than they might offer those in other countries have generally been more successful.

Partnership with or investment in a Chinese firm can also help to identify emerging threats and opportunities.

3. Realise the threat.

Companies that have been in a market leadership position for a long time can easily grow complacent. They need to continually strengthen their home base, ensure investment in innovation, and focus on their core strengths.

“The best advice for Western companies is to understand the challenges China’s innovators pose and consciously develop counter-measures,” says Greeven.

“Compete on their strengths, study the way China’s competitors do business, and rethink assumptions about how to innovate successfully.”

6 key traits of Chinese entrepreneurs

- A mindset that accepts disruption as business as usual.

- Collective action and information trading with other companies.

- Investment in product red and market innovation.

- Careful study of market trends to identify digital opportunities.

- Planning to go global from an early stage.

- Willingness to partner with multinational firms to foster growth.