Loading component...

At a glance

By David Walker

Australians hear it in political discussion, in business commentary, in casual conversation: Australia has an advantage in the 21st century, because the country is close to the booming economy of China and the Asian nations around it.

The Australian Government's 2012 Australia in the Asian Century white paper named Australia as "one of the developed countries closest to Asia" and argued that this gave its economy a "natural advantage".

Yet Australia is not quite as "close to China" or "close to Asia" as is often claimed. It's an impression created by the peculiar distortions of commonly used maps, and reinforced by a decade of commentary on Australian commodities shipments.

The former head of the Australian Treasury, Martin Parkinson, says the idea that Australia is close to China is simply wrong.

Parkinson put his view on the record in several speeches, the latest in November 2014.

He wanted to stamp out the view that closeness to China gave Australian service industries a special advantage. Australia might have a geographic advantage with China in commodities shipping, he admitted, but it had no such advantage in services industries.

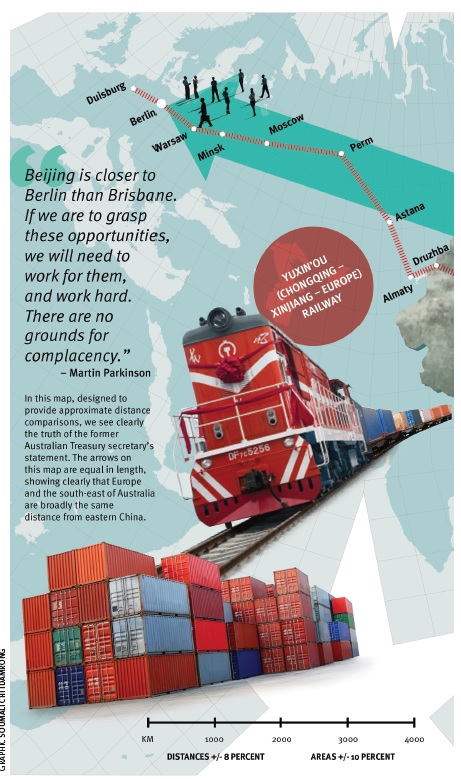

"Beijing is closer to Berlin than Brisbane," Parkinson declared in his November speech.

If Australia wanted to grasp the opportunities presented by China's growth, he argued, "we will need to work for them, and work hard."

Eight types of “close”

There are at least eight types of distance to which the phrase “close to China” could refer. Mostly, when people say “Australia is close to China”, it isn’t clear which “close” they mean. Let’s take them one by one.

Geographic distance between nations’ borders:

When two countries border each other, they’re usually close. On this measure Australia is fairly close to Indonesia, although the two countries are still separated by an expanse of sea.

But China? From Australia’s northern sea border to the Chinese sea border off Hainan is the better part of 4000km.

In border-to-border terms, that’s about the same distance as from Germany to Afghanistan, or Peru to the US, or Poland to China. Do we really think of Poland as being close to China?

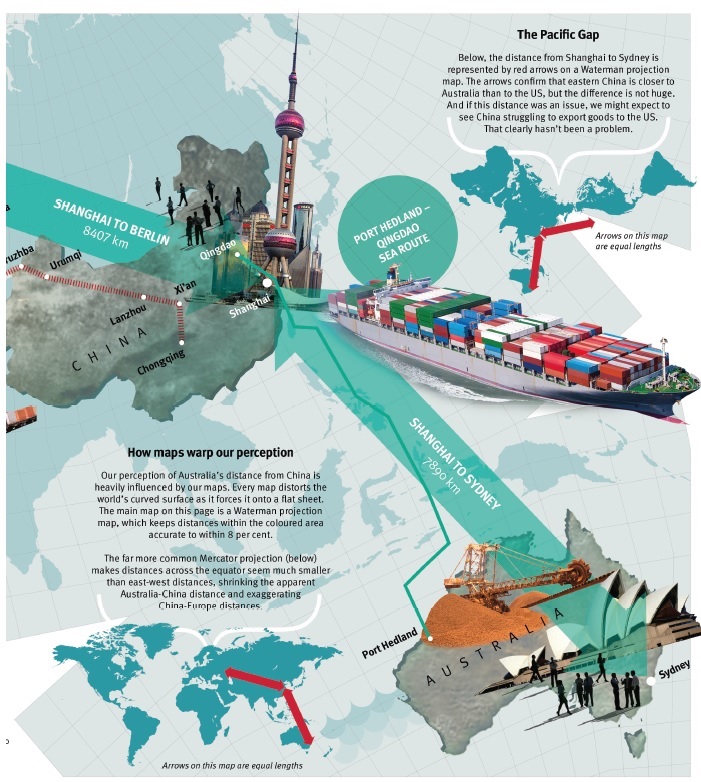

And if China looks a lot closer to Australia than Poland on a map, the short answer is that the map is messing with your head. Maps must attempt the impossible task of putting a curved surface on a flat plane, and most distort distances to do it.

The distances they usually shrink most are measurements across the equator. The most popular maps, called Mercator projections, are among the worst offenders. Our main map, below, uses a Waterman projection, which limits that distortion of distance.

Geographic distance between cities:

When big population centres are not far away on a map, we usually think of them as close. Think Helsinki and St Petersburg, or London and Paris, or Tel Aviv and Damascus.

From Sydney to Shanghai is 7890km, a bare 100km less than Tel Aviv to Shanghai and Warsaw to Shanghai.

Remember, if you think they look different on a map, that’s probably an artefact of the map’s projection. Even Darwin is almost 5000km from Shanghai – and with a population of 140,000, it doesn’t really loom large yet.

Australia’s main population centres are clustered in the south and east of the continent, the region that is farthest from China, so the distance from Australia’s big cities to anywhere in China is substantial.

Even the more southerly Chinese cities, such as Guangzhou, tend to be located more to the west. The distance from Sydney to Guangzhou is 7510 kilometres.

Personal travel time:

Closeness can also be a function of travel time. Flights from Sydney to Shanghai last 10 hours. Berlin to Shanghai takes about 11 hours.

Flight times from populated Australia to other parts of Asia are high, too. Sydney to Jakarta is more than seven hours, Sydney to Singapore more than eight.

Travelling to Delhi from Sydney takes more than 13 hours; you’d get there quicker on the nine-hour flight from London.

Time zone distances:

Travel times from China to Australia may be long, but perhaps people in the same time zone are effectively closer than people the same distance away across many time zones. That’s the claim of economists such as Shiro Armstrong, co-director of the Australian National University’s (ANU’s) Australia-Japan Research Centre.

Australia’s east coast is just two to three hours ahead of Shanghai.

“I would say it gets underplayed,” says Armstrong. “At the margin, it makes quite a big difference.”

Former Treasury head Parkinson disagrees.

“In a world that’s increasingly globalised and digitised, and where production can occur around the world, even the time zone advantage is overstated,” he told INTHEBLACK.

Shipping times:

Here Australia does have an advantage. Shipping LCD screens from Shanghai to Los Angeles by ship takes 19 days. Guangzhou to London via the Straits of Malacca and the Suez Canal takes 28 days. Guangzhou to Brisbane takes just 14.

More relevant for Australian exports, shipping from Port Hedland (the world’s tenth-largest port by tonnage) to China’s Qingdao (seventh-largest), with its huge iron ore terminal, also takes 12 days.

This gives BHP and Rio Tinto (which ships from nearby Dampier) a huge advantage over rival Vale, which takes 33-40 days to ship ore from Brazilian ports such as Tubarão.

Vale worries about this cost penalty a lot; the giant Capesize vessels which carry the ore cost almost A$100,000 a week to run, so every three-week disadvantage eats into their profits.

For the purpose of shipping screens to Australia or ore to China by sea, Australia really is closer to Asia than most other countries. But this advantage does not apply evenly.

In 2012 the Yuxinou Railway line opened between Chongqing and Germany. It can move goods from China’s laptop-producing capital of Chongqing, via Kazakhstan and Russia, to Germany in about the same time (12 days) that it takes to ship by sea from China to Australia.

Cultural distance:

Sharing language and culture can be the most important type of closeness. London and New York may be 5576 kilometres apart, but their people speak the same language – pretty much, anyway – and largely think along similar lines.

Melbourne and Toronto, on opposite sides of the globe, may be even closer, culturally speaking.

Outside its Chinese immigrant population, Australia’s general cultural engagement with China remains low. Most Australians don’t understand Chinese languages, literature, philosophies, religions or art.

CPA Australia’s 2013 report, Australia’s Competitiveness: From Lucky Country to Competitive Country, makes this point strongly.

Markets like China, the report notes, are “geographically closer, but culturally far more different, to Australia than the traditional markets”.

Economic distance:

When high volumes of trade or investment pass between two countries, they can be called close.

And Australia and China, with two-way trade worth A$150.9 billion (roughly two to one in Australia’s favour) and two-way investment stocks of A$61.5 billion in 2013, certainly qualify as close.

ANU economist Shiro Armstrong argues that Australia’s supply of raw materials to China – A$52.6 billion of iron ore and concentrates alone in 2013 – “basically underpins their development and economic security”.

Is Australia close to China? In this sense, yes: the two countries sell each other a lot of stuff.

Martin Parkinson argues, though, that this gives Australia no inherent advantage in China in other fields, such as services.

Lessening the distance handicap:

There’s one final sense in which Australia can be said to be close to China, although it’s not so much “close” as “closer”. It’s emphasised in the Australia in the Asian Century paper.

Australia is a long way from East Asia, but it’s even further from almost everywhere else, so China and East Asia matter more to Australians. Shanghai may be 10 hours away, but Los Angeles is 15 and London more than 20.

As CPA Australia’s Australia’s Competitiveness: From Lucky Country to Competitive Country report says, many of Australia’s large markets will be closer in the future than they were in the past.

Research by Australia’s Treasury has shown that distance does leave Australia at an economic disadvantage. If south-east Australia were in the middle of the Atlantic Ocean, we might well expect the economy to be 10 per cent bigger.

Even in a digitised and globalised world, distance still matters. To the extent that Australia is not handicapped against other advanced economies in its dealings with China, it’s possible that the country is better off.

But “Australia is no further away from China than many other places” just doesn’t have the same ring, does it?