Loading component...

At a glance

- Many of the most significant dress code changes throughout history have been caused by major events such as World Wars.

- Corporate dress codes offer a shortcut in terms of decisions about attire, but also go a long way in communicating an organisation’s culture and brand values.

- Events of the pandemic have opened up conversations about what the next shift in dress codes could look like and how more comfortable work attire could boost productivity.

When Australia entered the Second World War, enlisted recruits had to be aged between 20 and 35. Later, the age range was expanded to between 18 and 40.

Across the army, navy and air forces, more than 990,000 Australians – or just over 10 per cent of the population – enlisted or engaged in combat, with more than 555,000 serving overseas.

Australia lost 27,073 soldiers in the war and just over half a million individuals, mostly young men, returned to its shores when the war was over.

What does this have to do with workplace dress codes? Plenty, says Dr Lorinda Cramer, postdoctoral research fellow at the Australian Catholic University’s National School of the Arts.

Cramer is working on a project investigating the social and cultural history of men’s clothing in Australia over the past 100 years. Major events, such as world wars, and the new economic, social and international pressures they bring, shape current and future trends, according to Cramer.

“Dress codes have changed dramatically, or sometimes in quite subtle ways, during the 20th century in response to or following major upheavals,” says Cramer, who spent 15 years working as a curator and collection manager in museums before taking up her academic post.

“One of the reasons we saw major changes in dress code following World War II was because clothing was in very short supply. Australia had been subject to austerity measures since 1942 that included the rationing of food and fuel, but also clothing.

“As servicemen began to return from the war, they were supposed to be issued with a ‘civvy suit’. Government authorities recognised that a lot of men were young when they enlisted, and that when they returned, they might no longer fit in the clothes they had previously worn.

“Authorities also acknowledged that they needed something appropriate to wear following demobilisation, so they could feel confident as they transitioned from ‘soldier’ to ‘civilian’.”

However, there were shortages. Cramer explains that, at the time, Australia’s wool mills were working at capacity and that tailors struggled to keep up with the demand for civvy suits.

This led to many people questioning whether it was time for this massive returning population to wear something more relaxed than a three-piece suit.

“Before World War II,” Cramer says, “Australia looked towards London for fashion. In the post-war period, there was a shift, as Australia started to take its cue from America, particularly California.

“California leisurewear was a relaxed style of clothing that had become increasingly popular across America.

“Australian commentators, influenced by well-dressed American GIs who came to Australia during the war and by Hollywood’s movie stars, suggested men should be able to adopt sportswear, such as separate sports jackets and trousers, and woollen cardigans and jumpers, for their return to the office.”

While everyday men’s fashion started to gravitate from three-piece suits on account of material scarcity, the changes in women’s fashion were the product of departure from the years of being compelled to wear the “austerity suit” – a short, straight skirt and a jacket with no more than two pockets and four buttons.

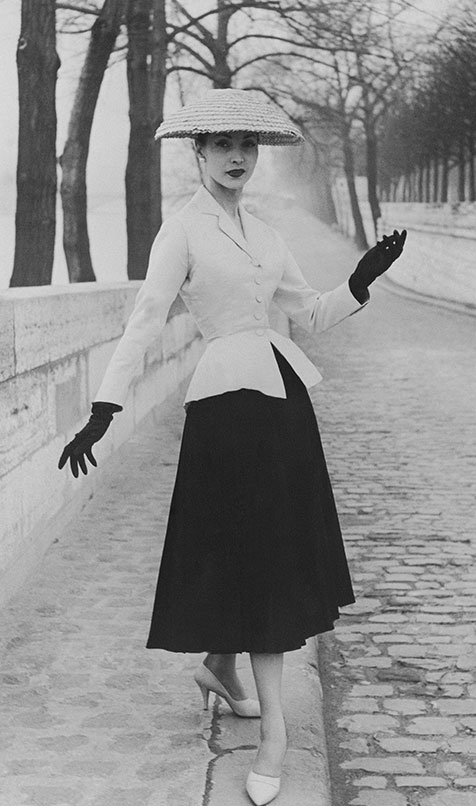

Paper, fabric and colour film gradually became available after the war, bringing back better-quality fashion magazines that featured Christian Dior’s revolutionary “New Look”, which debuted in February 1947 and became known for its clearly defined “feminine” silhouette complete with rounded shoulders, a cinched waist and a full, A-line skirt.

Although there were protests against what were seen as regressive ideas behind all the embellishments and exaggerations, and the look all but vanished in the 60s, it saw a revival in the 1990s, which has extended to updated takes on the style in the early 21st century.

Not just appearance

As the COVID-19 pandemic sent countless white-collar workers into home isolation, and wearing casual pants during Zoom meetings became our “new normal”, the effect on acceptable business attire is arguably greater than any post-war change.

Before we can speculate on what post-pandemic workplace wear would look like, its vital to understand why we dress a certain way when we head off to the office.

Having a dress code, or a dress convention, removes or limits the element of choice, which could actually confer a psychological benefit by offering a shortcut.

“Think of Steve Jobs,” says Sofie Carfi CPA, lecturer at Australian College of the Arts and founder of Fashion Revival Runway, which promotes sustainable fashion and independent Australian designers.

"You never get a second chance at a first impression. We judge each other when we first meet, largely on appearance, because that's all the information we have. So, dress code communicates information within and outside an organisation."

“He wanted the ease of not having to think about certain things, such as what to eat or what to wear. So, he wore the same outfit every day – his uniform of sorts – and often ate the same food for months at a time.

“What about the corporate suit and tie? That’s a uniform, too. Everyone wears dark colours. Everybody blends in. Nobody wants to stand out.”

Colour has a psychological effect, Carfi says. Many men and women working in the law and finance sectors, for example, wear dark grey, dark blue and black clothing.

“People might wear a white shirt, but their main colours are very neutral,” she says. “Once again, they don’t want to stand out. They want to blend in and create an aura of reliability and conservatism.

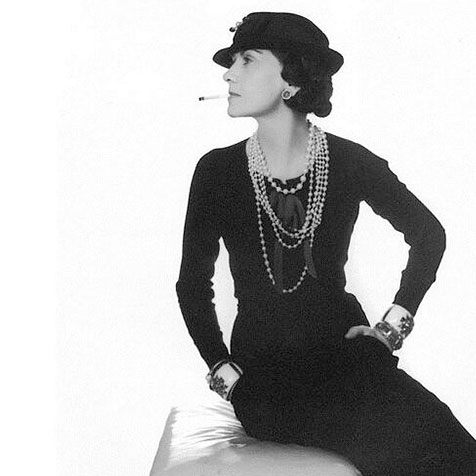

“That’s the psychology around the ‘little black dress’, invented by Coco Chanel. Got nothing to wear? Put on the little black dress, and you’ll fit in. If you want to stand out, what are you going to do? You’re going to wear the red dress, the yellow dress or the backless dress.”

When an industry, a company or an individual wants to broadcast solemn professionalism, security, consistency and trustworthiness – or, on the contrary, creativity, daring and artistic flare – dressing a certain way helps communicate brand values.

Clothing speaks volumes

Communicating brand values, in fact, is one of the main purposes of any workplace dress code, says Sarah Lawrance FCPA, founder and “chief dreamer” of Sydney accounting firm Hot Toast.

“Everything we do at Hot Toast, from the adoption of technology to how we talk to our clients, to how we present ourselves, creates a particular perception. It is how we want to come across to you,” Lawrance says.

This means that, before developing a dress code, a business’s leaders must first develop an intimate understanding of the culture the organisation wishes to embody and communicate to its market.

At Hot Toast, you won’t catch staff wearing suits. Instead, Lawrance says, the dress code is relaxed but stylish.

“My background is in the creative industries, and we now tend to specialise in those industries,” she says.

“You never get a second chance at a first impression. We all judge each other when we first meet, largely on appearance, because that’s all the information we have. So, dress code communicates information within and outside an organisation. In this business, we need to look professional but not ‘suited and booted’, because our market – creatives and startups – don’t relate to the ‘suit culture’.”

Having worked in the advertising field for many years, Lawrance says every small detail is important in communicating a brand.

"Track suit pants and slippers will never be appropriate, but why wouldn't we take steps to ensure staff are as comfortable as possible? It makes sense to talk about this right now, since the pandemic has paved the way."

“I want us to feel like an extension of our clients’ industry, an extension of their business,” she says.

“You can’t do that if your client works, and communicates, and looks a certain way, and your culture is clearly different to theirs.”

Paul Luczak CPA, director of The Gild Group, agrees. Having started in the music and entertainment sectors, where many people have “never worn a suit, never worn a tie, struggled to even wear a shirt”, he jokes, The Gild Group’s dress code is now more like that of an advertising agency than a traditional accounting firm.

Staff dress to suit their client base, Luczak says, and that’s simply common sense. His business works across numerous industries, and never has he had to reprimand a staff member for underdressing or overdressing.

“In our handbook, there is a comment on dress code, but, once inducted, people learn pretty quickly about dress code and culture,” he says.

How then does a business identify and define its own culture, and therefore decide on a suitable dress code to help communicate that culture?

Luczak says it’s as simple as looking to your clients and deciding what they’d be most comfortable with.

It is also about considering what types of talent you would like to attract into your business. Luczak says he is interested in “high-performance, entrepreneurial, SME-loving people who want to work with very dynamic brands”. The business’s dress code helps, in its own small way, to bring them in.

Carfi recommends approaching your clients and asking them what they expect in terms of dress code. More than a few partners in large accounting firms have bemoaned Casual Fridays, because they say clients are sometimes mildly shocked by the fashions they witness.

Those organisations and others would benefit from allowing client feedback to help guide their dress code guidelines.

“You wouldn’t wear a bikini to a funeral,” Carfi says. “It’s important that all staff always wear what clients feel is appropriate.”

The challenge comes, says Lawrance, when you are doing business across cultures. She says colleagues from across the Asia-Pacific tend to dress formally even though they are working from home.

“Some regions are a little bit more conservative, so it’s important to always remain aware and respectful, even if it’s just a Zoom meeting,” she says.

New decade, new rules?

The remote working environment has introduced a different dimension to appropriate workplace attire.

“I think for your traditional accounting practices, where suits and ties are worn, that has introduced significant changes,” Luczak says.

“I’ve noticed quite a bit of a change in how people present themselves in video meetings. People who are usually in a suit jacket are now in a T-shirt.”

Growing awareness of climate change, as well as supply interruptions caused by the pandemic, means trends and fashions are also likely to change as individuals seek out “slow fashion”, Carfi says.

“People are going to smaller designers, and discovering local brands, and getting to know those designers and discussing the outfits with them,” Carfi says.

“Technology means people are able to personalise their clothing and order shoes in a unique colour.

"Fashion is becoming more fluid and based less on annual collections. Much of this is a result of changed behaviours around the pandemic.”

Most significantly, Cramer believes the working-from-home and video-call experience has shown us that people work very well, in some cases even more effectively, in casual clothing.

“In 2020, I saw colleagues wearing things that surprised me, but at the same time I knew they were doing the same amazing work they always did,” Cramer says.

“It’s possible that slightly more casual clothing, looser-fit tailoring and lighter fabrics that are better for the heat will become more acceptable in offices.

“Now is the perfect time for these conversations to be had, about what people wear to the office and whether it should change. Track suit pants and slippers will never be appropriate, but why wouldn’t we take steps to ensure staff are as comfortable as possible?

"It makes sense to talk about this right now, since the pandemic has paved the way.”