Loading component...

At a glance

By Sarah Frier

On the last day in January 2017, about two dozen prolific users of Facebook were invited to the social network’s headquarters in Menlo Park, California.

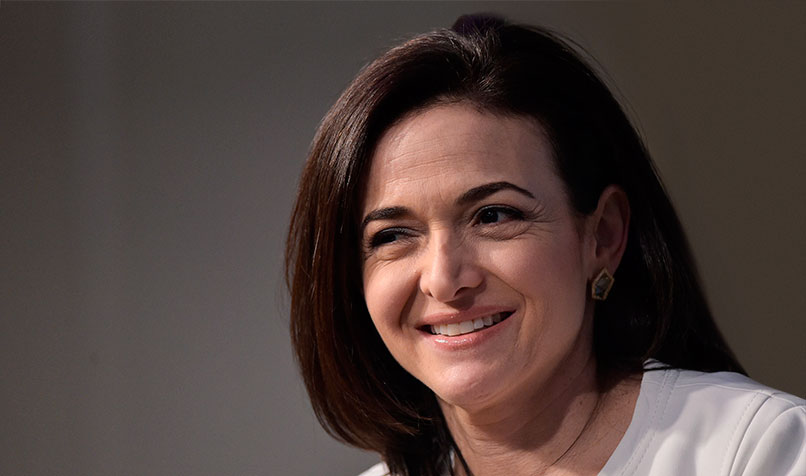

There, they were arranged on a circle of brightly coloured chairs to meet Sheryl Sandberg, the company’s second-highest-ranking executive and the Oprah Winfrey of corporate America.

The guests, who had made life-changing friendships using an organisational tool called Facebook Groups, were invited to ask Sandberg questions. She insisted that she had to hear their stories first.

That’s when the tears started flowing. A woman talked about how a Facebook post on her struggle to become a mother led her to adopt a foster child; two women from opposite coasts discussed how they’d become close by starting a private group to help women of colour navigate mental-health issues; and a Dallas waiter who’d lost his leg because of a rare bone disease talked about meeting a man who’d helped him raise money to try out for a soccer team for the disabled.

Sandberg, dressed in a loose white sweater, jeans and boots, California quiet-luxury style, leaned in, over and over, to listen, offering words of encouragement and hugs.

“I love this,” she told them.

After the sudden death of her husband, David Goldberg, two years ago, she was comforted to know that Facebook was helping others cope with their own hardships.

As they talked, cameras and boom mics followed; members of the press looked on from the edge of the room.

The publicised event was in celebration of Friends Day, a Facebook-conceived holiday with all the authenticity of greeting card company concoctions like Grandparents’ Day.

However, really it was just another normal morning at Facebook, where employees are generally encouraged to share their personal challenges with colleagues.

Nor would the event have been out of place in the emotionally well-adjusted atmosphere that now characterises many corporate cultures, thanks in large part to Sandberg herself.

On Friends Day, Mark Zuckerberg, Facebook’s CEO, also enthusiastically joined the festivities, but when guests were asked for the highlight of the trip – dinner out in Palo Alto or the session where they got to give product advice? – one woman quickly answered, “Getting a selfie with Sheryl.”

Bring your whole self to work

Sandberg’s message of openness and empathy may come across as a self-serving schtick. Facebook’s COO encouraging people to overshare is like Exxon Mobil promoting oil.

Yet since she’s one of the most powerful women in business, you can’t just dismiss her as the Chief Emoting Officer. There’s what Sandberg has accomplished at Zuckerberg’s side – Facebook is, with a market value of US$425 billion, the world’s fifth-largest company, and affects the daily lives of its almost two billion users.

There’s also her harder-to-quantify role as this decade’s leading culture shifter in the long slog toward a corporate reality in which winning doesn’t require posing as a man.

Decades ago, pioneering feminists such as Betty Friedan and Gloria Steinem pointed out that compartmentalising domestic and professional spheres was a way for men to stay in charge.

Because women can’t hide the fact that they’re pregnant or breastfeeding, simply being female looked unprofessional.

And as long as problems related to child care and other forms of domestic labour – traditionally the purview of women – weren’t seen as work, public policies would never change and women would never become part of political decision-making.

The foremothers of today’s female CEOs organised women to become a vocal force asserting that their issues were collective ones, but over the years the pace of change slowed.

Sandberg, in her blockbuster bestseller Lean In: Women, Work, and the Will to Lead (co-written by Nell Scovell) and through her non-profit LeanIn.Org, picked up the thread, encouraging women to get together online and in person to share the struggles and feelings involved in bridging those still-present divides.

Sandberg’s central management message was a compelling one: “Bring your whole self into work.”

She’d conveyed this inspirational thought in a commencement address to Harvard Business School, her alma mater, in 2012, the year before the book was published.

The slightly paradoxical idea was for women to drop their professional facades and convey vulnerability to better connect with colleagues and customers, while at the same time acting with the confidence needed to rise in the workplace.

Now, with the publication of a new instructional memoir, Option B: Facing Adversity, Building Resilience, and Finding Joy, Sandberg has taken that cause even further, moving workday anguish over setbacks such as divorce, disease and death from solo crying in the office car park to company hallways, conference rooms and boardrooms.

After Sandberg became a widow and the single mother of a primary-school-age son and daughter, she was vulnerable in a way she couldn’t control.

“If I believed before Dave died in bringing your whole self to work, what I learned after Option B is you have no choice,” she says during an interview at Facebook.

“When your whole self is going through adversity and tragedy, that whole self comes to work.”

In the book, co-written with Wharton School professor and TED Talk superstar Adam Grant, she weaves her family’s story of loss with academic data on recovery from tragedy and with anecdotes from others facing cancer, disability or mental illness.

The title refers to a conversation Sandberg had with her friend Phil Deutch, a managing partner at an energy fund.

As she recounts in the first chapter, called “Breathing Again”, he offered to fill in for Goldberg at a father-child school activity. “But I want Dave,” Sandberg writes.

Deutch put his arm around her and said, “Option A is not available. So let’s kick the shit out of Option B.” Back at work, motivational posters encouraging people to “kick the shit out of option B” went up all over the sprawling Facebook campus.

An accidental prophet of openness in the workplace

Sandberg doesn’t have an office in the den of transparency that is Facebook, but she does have a personal conference room: a glass-walled case with a table, right in the middle of all the standing desks and modernist furniture.

On a recent Tuesday between meetings, she uses a spare moment as many workers do: checking for comments on her most recent Facebook post, an announcement of the upcoming book. Unlike most people, she has thousands to wade through.

One comment jumps out at her, from a woman who says her husband died a week after Goldberg passed away.

“She went back to work after 10 days because I did,” Sandberg says, folding her hands over her chest while seated in her conference room.

“I would never want anyone to lose their husband at 47. Ever. But given that it happened, isn’t it incredible that I feel connected to her? After the post this morning, I feel less alone.”

Sandberg exudes such intense sincerity when she talks that it can come across as manufactured. Her eyes fix on listeners as she takes them through data, a vignette, and a handy concluding sentence – exactly the package they need to convey it to someone else.

Her tone is one you’d use talking to a close girlfriend, though her sentences end with her voice falling, which underscores the seriousness of what she’s saying. Her conversations incorporate calculated pauses that provide opportunities to absorb her message.

She’s disciplined, too. Even when she’s telling recycled stories and jokes, friends and colleagues who’ve heard them before marvel that she can deliver them with fresh emotion and impact.

"When your whole self is going through adversity and tragedy, the whole self comes to work."

Sandberg contends that she’s almost an accidental prophet of openness in the workplace.

A decade ago, as an executive at Google, she always worked from 7am to 7pm. Then her first child was born, and she found she couldn’t stand coming home to find him already asleep.

She started sneaking out of the office early, sometimes placing a decoy jacket on her chair, leaving the light on at her desk, or scheduling afternoon meetings in other buildings so her colleagues wouldn’t see her leave.

The subterfuge continued for years. Then in 2012, about a month before Facebook’s initial public offering, she admitted to a reporter that she regularly left work at 5.30pm.

The revelation blared across multiple news outlets. Sandberg was worried that she would be lectured or fired.

Instead, her brazenness was heralded by other female professionals. The women of the legal team at Yahoo! sent her flowers with a card saying that they, too, were leaving at 5.30.

“I didn’t realise how much noise there would be,” Sandberg says.

“A friend told me, ‘You couldn’t have gotten more publicity if you murdered someone with an axe.’?” (This was in the innocent days before Facebook Live, the streaming video service, was used by murderers for PR.)

When she submitted the Lean In manuscript to editors later that year, they told her that the first draft was boring. It was all data and research, with nothing about her own challenges navigating the workplace obstacle course of gender expectations and entrenched sexism.

Her husband told her nobody would read it if she didn’t put herself into it. She began rewriting. Sandberg says she didn’t want to overshare, but apparently the market was demanding it.

When Goldberg died, she regretted the fame the book had brought her.

“If I could have gone back and rewritten Lean In, I would have, because I didn’t want to live publicly,” she says. “But then it was so isolating.”

People avoided her gaze. Interactions became stilted. She confided to Zuckerberg that she felt as though her workplace friendships were melting away.

One night before bed, she wrote a 1700-word explanation of what she was going through and how she hoped people would interact with her. It started as a cathartic exercise.

She didn’t think she would publish it, but when she woke up, she changed her mind and put it on Facebook. In Lean In, Sandberg had admitted to crying at work (another confession the media jumped on), but this was the first time she’d shared anything so deeply personal. The post received 74,000 comments, many from co-workers acknowledging her struggle.

Of course, one could argue that Sandberg had begun down this path the moment she joined Facebook – a company that earns billions from getting people to open up about their lives. She and Zuckerberg have frequently been asked to lead by example.

When Facebook lifted a tactic from Twitter and gave public figures the option of opening their profiles to people who weren’t friends but followers, “I wasn’t going to do it, and neither was Mark,” Sandberg says.

Then a communications executive, Caryn Marooney, told them they would have to do it if they wanted others to fall in line. “I think the product has really changed us,” Sandberg says earnestly.

Zuckerberg gives her a lot of credit, too. “When Sheryl first came to Facebook, she started a tradition of checking-in to our leadership meetings,” he wrote in an email.

“Checking-in” means each person around the table is invited to discuss their current emotional and professional state before they get down to business. “Nine years later, we’re still doing it.”

Sharing stories

In 2014, Sandberg hosted an all-hands meeting to talk about the connection between sharing personal stories and working at a place like Facebook. She talked at length about the company’s culture and how employees were individually charged with serving its mission “to make the world more open and connected.”

Then she introduced some employees, whom she now describes as “a bunch of people who went onstage and shared a lot of really personal stuff, things they’d gone through and how Facebook connected to it.”

One employee who got the message was Stephanie Latham, a marketing director who coordinates Facebook’s relationship with the auto industry and had just relocated to Menlo Park when she found out she had cancer and was pregnant. Reluctant to post about her personal life, she told only her team, so they could prepare for her unpredictable schedule.

Soon after, a group of her co-workers, including some she didn’t know, produced a video for her, set to Pharrell Williams’s Happy. Latham was moved to tears.

News of the video reached Sandberg, who encouraged Latham to share her story at Facebook’s internal Women’s Leadership Day conference.

“That was way out of my comfort zone, but I felt like it was a necessary thing to do,” Latham says in an interview.

The episode sounds like a scene from The Circle, the best-selling thriller by Dave Eggers that’s just been released as a feature film starring Emma Watson.

In it, employees at a Facebook-like company are svengalied into making their lives and emotions transparent, as a precursor to totalitarian thought control.

In real life, Latham’s story didn’t end in treachery and murder; it just went viral on the company’s internal network. Responses from colleagues were accompanied by the hashtag #FBFamily, which was later printed on blue rubber wristbands and passed around. Latham, now cancer-free with a healthy daughter, credits Sandberg for helping her find a supportive community at work.

“She leads so strongly by example,” Latham says.

Ample sharing among colleagues is inculcated in employees from the second they walk in the door. New hires are invited by the HR department to a Facebook group of their peers and are expected to befriend one another and members of their future teams.

Collaboration among all employees occurs on Facebook Groups. Milestones and failures are publicised on the network, as well as “Faceversaries” – anniversaries of workers’ start dates.

These are hallowed events, acknowledged like birthdays, with hundreds of celebratory posts from colleagues and a note from the employee reflecting on what he or she has learned, while tagging the bosses and co-workers who made it all possible.

Many workers find the approach freeing. In February 2016, an engineering director named David Ferguson posted to the global Facebook employee network an explanation of why, the following Monday, she would arrive as a woman and go by the name Deb. I

n September, Oscar Perez, a diversity director who posts about life as a gay Latino, shared thoughts about the day his father became a US citizen.

“You think it would waste time, to sit around and talk about your life, but it doesn’t,” says Sandberg.

“It actually saves time, because it’s so present for people that having an opportunity to talk about it actually helps.”

Wielding soft power, even with Wall Street

Facebook celebrates the values of transparency and personal sharing with the exuberance of a company that knows it might be very good for business. But the Sandberg effect is now showing up at places that don’t capitalise on the human urge to communicate.

Mary Barra, the CEO of General Motors, posts on Facebook about issues such as female empowerment. Another close Sandberg friend, Walmart CEO Doug McMillon, responds to customer complaints on the social network with his personal email address.

This year he became the first chief executive to be featured in one of the retail giant’s commercials. (“The reason I share? I’m proud of the people I work with.”)

It’s Sandberg-inspired postmodern marketing – a corporate attempt to strengthen bonds with customers via an abundance of sharing that in a prior era might have seemed unbecoming.

“It makes us trust them more, or at a minimum, know them more, and that’s good for loyalty over time,” says Mike Hoefflinger, a former Facebook employee who wrote a book about the social network.

“This younger generation really craves this authenticity, this vulnerability,” explains Kellie McElhaney, a professor at the University of California at Berkeley’s Haas School of Business. She sees Sandberg as far ahead of the game.

“When I hang out with these most powerful women, particularly in tech, they’re just like machines,” McElhaney says, recounting a time she overheard two female executives compare the results of blood tests to measure their testosterone levels.

Among the churn of leadership books, a more recent set has emerged promising to teach authenticity and touting research showing that those in upper management who master it will have more sway.

Sandberg employs this soft power even in her conversations with Wall Street. Before Facebook’s earnings reports are published, her team helps her gather compelling anecdotes from advertisers that take advantage of the company’s user-targeting tools. She keeps the stories in a list beside her, to use as examples on the investor call that accompanies the quarterly release.

“I’m doing that on purpose, on earnings calls and in all my communication, because stories are what help us understand things,” she says.

If the company’s new product, Workplace, succeeds, Sandbergian management will have proven to be scalable. Various Silicon Valley start-ups have tried to create versions of Facebook for work; Slack Technology, the creator of a popular office messaging service, is now valued at US$3.8 billion.

Facebook’s answer provides an office-friendly version of its standard newsfeed – and a justification for employees to spend even more time on the network. Early adopters include Starbucks, Viacom and the Singapore Government.

"Even with plenty of money and help, being a single mother makes leaning in hard."

The attention Sandberg’s book is getting comes at a good time for Facebook.

The company has arrived at a moment when it desperately needs to be humanised – when, now unimaginably large and influential, it’s under assault on a number of fronts, for how criminals use Facebook Live, for enabling the proliferation of extremism, and for elevating fake news, which some critics blame for the election of Donald Trump.

During Barack Obama’s presidency, Silicon Valleyites were comfortably ensconced with the liberal elite; suddenly, they’re being cast as work-visa-abusing, terrorist-enabling globalists.

Sandberg, who supported Hillary Clinton’s presidential candidacy, demurred in 2016 when asked if she would accept a political appointment from the first female commander-in-chief, but there was speculation she might be nudged.

This year looked like an Option B for Sandberg politically, too, and she’s not kicking the shit out of it. After she failed to write about January’s Women’s March protests, a local tech blog, Pando Daily, penned a scathing post, charging that her silence was evidence that Facebook was “bending over backwards to embrace a Donald Trump world”.

Sandberg later conceded that she should have posted about the event; then she sent a donation to Planned Parenthood.

Asked how she decides what to post publicly, she says, “I care about the issues I care about. I care about women. I care about resilience. It’s like anyone else.” She spends more time on the posts about “big stuff,” like one she did for Mother’s Day the year after her husband died, in which she talked about criticisms Lean In had received for its assumption that all women could lean in, neglecting to sufficiently address the reality of, for instance, solo mothers with low-wage jobs.

Now, she explained, she’s painfully aware that, even with plenty of money and help, being a single mother makes leaning in hard. With the publication of the new book, Sandberg is prepared for fresh criticism, this time for her personal choices. Tabloids are already commenting on her dating life. Everyone has a different idea about how someone should grieve, she says.

Sandberg has been at Facebook for nine years – “a long time for anyone to be anywhere,” she says. But even though her name is frequently associated with high-level roles, such as CEO of Disney or California senator, she says she’s not going anywhere. Her argument is, as always, deployed with data and a handy vignette.

Research shows that after experiencing a death, it’s common for people to want to do something meaningful with their lives, she says. She thinks her work at Facebook is more meaningful than ever.

In a sense, the company is a kind of wealthy nation-state unto itself – one that might grant her more influence than she would have as a politician.

Alongside encouraging warm, open conversation among employees, she and Zuckerberg have implemented longer bereavement plans and more flexitime for coping with life tragedies, policies which, if they spread to other companies, would offer a tangible pay-off for all this job-mandated vulnerability.

“I work on something I really believe in with my best friend. I think I’m doing this,” she says of her intention to stay put. “I don’t know how many times to say it.”

Used with permission of Bloomberg L.P. Copyright © 2017. All rights reserved. Photos © Robert Maxwell/Cpi Syndication/Headpress and Getty Images.