Loading component...

At a glance

Finding a good job is usually a high priority for 20-year-olds, especially if a university degree is not taking up most of their time and delaying this milestone.

However, US macro-economist Erik Hurst is warning that men in their 20s with low education levels are increasingly satisfied to be out of the labour force.

The reason could relate to economist Edward Castranova’s observation that “we are witnessing what amounts to no less than a mass exodus to virtual worlds and online game environments”.

Dwindling numbers of men at work

“Look at these numbers,” says Hurst, pointing me to research that he’s sharing online from his office at Chicago Booth University, School of Business.

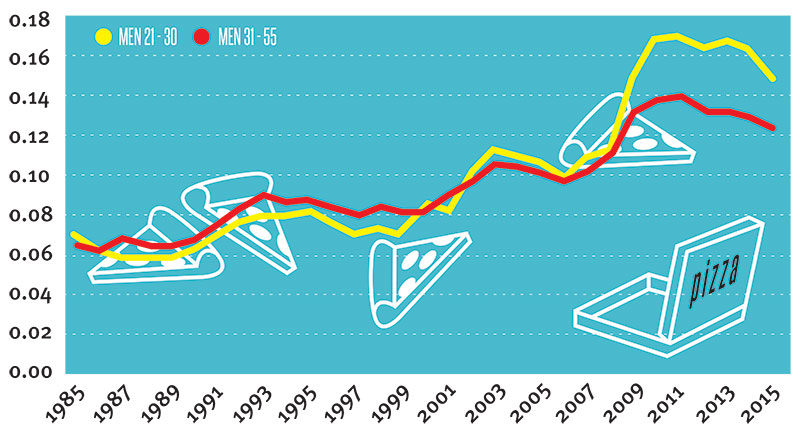

“This is the graph that really gets people.”

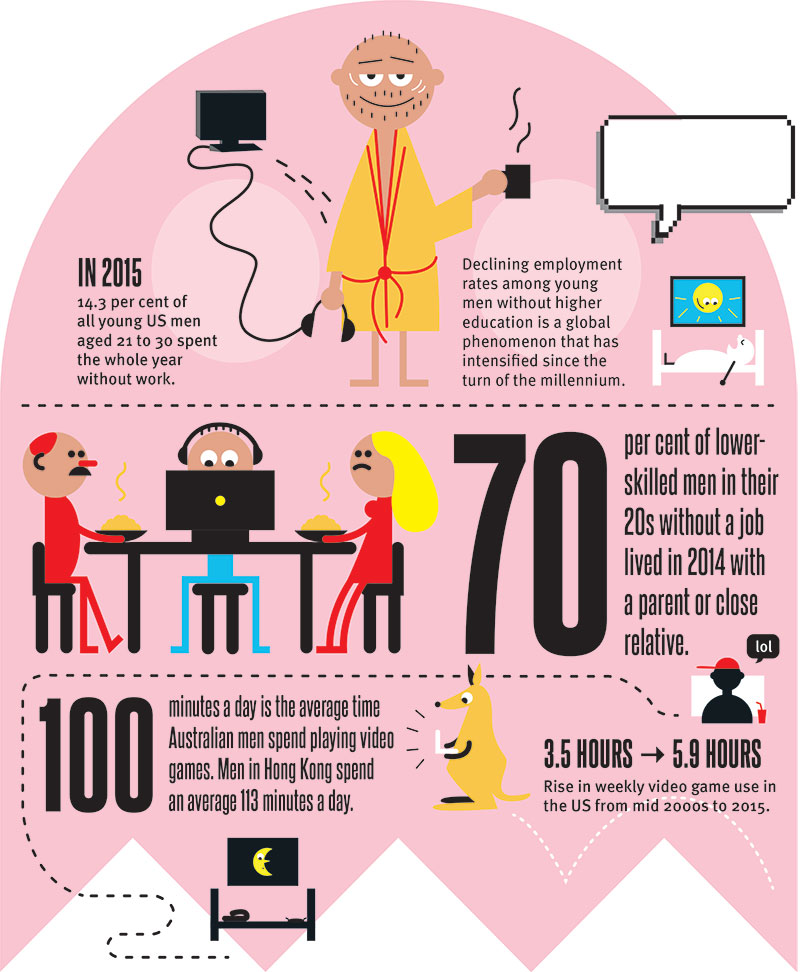

The graph ("fraction of men in the US who report working zero weeks in the year"), shows that in 2015, 14.3 per cent of all young US men aged 21 to 30 spent the whole year without work.

For young men without a bachelor’s degree, the situation is worse – 17 per cent sat idle all year. In 2000, only 8 per cent of young men without a bachelor’s degree fell into this category.

These figures exclude any men who were out of the workforce due to study.

“This kind of decline is staggering and, historically, unprecedented,” says Hurst, “and it’s larger than for all other sex, age and skill groups during this same period.”

Graphs such as this make politicians and parents feel twitchy. Very twitchy. It doesn’t bode well to have men in their prime with nothing to do.Declining employment rates among young men without higher education is a global phenomenon that’s intensified since the turn of the millennium, says Dr Patrick Carvalho, a senior economist in a finance advisory company in Washington, D.C.

Last year Carvalho was focused on youth unemployment in Australia as a senior research fellow at the Centre for Independent Studies in Sydney.

He says we don’t know all the factors at play, but the technologies that automate repetitive, low-skilled jobs have played a large role in displacing men from their jobs, especially in manufacturing.

Technology has also increased the complexity of tasks in every work sector, including those jobs a high-school leaver once did easily.

“It’s become so much harder for someone to get a steady, well-paid job without a degree, and when there is an economic downturn it’s the less educated who are the worst hit,” says Carvalho.

Technology offers an enjoyable lifestyle

Much has been written about digital technologies eliminating jobs. However, in the search for other culprits responsible for keeping young men off the payroll, no one has mentioned World of Warcraft or Perfect World as a causal factor. Until Hurst.

His analysis of data from the US Bureau of Statistics’ American Time Use Survey found that, on average, men in their 20s without a bachelor’s degree increased their leisure time by about four hours per week between the early 2000s and 2015.

They gained this extra time through loss of work. Of that additional four hours of leisure each week, 2.5 hours were spent playing video games.

On average, video game use rose from 3.5 hours per week in the mid 2000s to 5.9 hours per week by 2015. A quarter of young unemployed men reported playing at least three hours per day; 10 per cent played for six hours daily.

These levels aren’t surprising. Video games have captured the hearts and minds of young men in general, and for the unemployed who have extra time on their hands, it gives them something interesting to do.

What really captured Hurst’s attention was these men’s life satisfaction scores – they were getting happier at a time when their job prospects were plummeting.

Eighty-one per cent of men aged 21 to 30, without a bachelor’s degree, rated themselves as “very happy” or “pretty happy” between 2001 and 2005. This rose to 88 per cent over the 2011 to 2015 period.

At the same time the happiness level for older, less educated men aged 31 to 55 was dropping, data from the US’s General Social Survey shows.

This made Hurst wonder if young men were enjoying their video games so much that, along with the cheap food and the free accommodation they were getting in their parents’ houses (in the US in 2014, 70 per cent of lower-skilled men in their 20s without a job lived with a parent or close relative), they were choosing not to work because this lifestyle package was too good to forfeit for a low-paid job.

Hurst ran a series of analyses, drawing on national employment and leisure time data.

This generated a provocative estimate: video gaming among young men without a bachelor’s degree explains 20 per cent of the decline in employment rates in the US over the last 15 years.

In other words, technology could be reducing labour supply as well as labour demand, although as Hurst explains: “The bulk of the reason for declining employment is not video games, but it explains a non-trivial chunk.”

Could the enjoyment of video games be so great that it buffers against the disadvantage of unemployment and bolsters life satisfaction?

In 2013, Videogames and Wellbeing: A Comprehensive Review, by the Young and Well Cooperative Research Centre’s Gaming Research Group, came out in defence of the role of video games in young people’s lives.

It concluded that video games, if not played to excess, can have a positive effect on young people’s vitality, engagement, competence and self-acceptance, depending on how and with whom you play.

Gamers with useful high-level skills

If video games can improve wellbeing, could they also serve to improve users’ employability? Assuming Hurst’s estimate proves correct – that video games are responsible for 20 per cent of the decline in employment for young men without a bachelor’s degree – that represents a huge opportunity to make video games part of the solution.

In her 2012 TED talk, “Gaming can make a better world”, game designer Dr Jane McGonigal described how she designed games that translate the “epic wins” you can experience online into behaviours that can make a positive difference in our real lives. We can, and should, harness game power to solve serious world problems, she says.

Why disengagement is a problem

Lack of education and lack of employment among men are strongly associated with crime, drug abuse, domestic violence and social disruption. It’s a serious problem.

Economically, the concern is that the more time a man spends out of the workforce, the less likely he is to get back in, and the fewer workers there are, the more the tax base shrinks and the more government services are used.

This can make for a poorer country and falling living standards.

“These young men represent an important section of our society that we are failing to integrate and offer a decent life,” says Carvalho.

He cites psychology pioneer Sigmund Freud, who once said that the two main things that define a person are love and work.

“If you are a single young male out of a job, then that’s very challenging to your identity.”

We’ve worked out how to use the internet to help people find love. It probably won’t be too long before we figure out how to use the online world of gaming to help young men upskill and find work.

Mark's perfect world

Mark [not his real name], a 28-year-old from the central coast of New South Wales, has been unemployed for much of his 20s. He works a couple of days a week but considers himself underemployed, so is applying for other jobs.

He currently plays Perfect World, a MMORPG (massively multiplayer online role playing game), for 16 hours per day when not working, and puts in about five hours on a work day, before starting and after finishing his day job.

Mark says gaming gives him a chance to demonstrate his skills, while keeping him connected and informed.

“If something happens in the world I hear it first from other players on Perfect World. It also offers relief from the reality that there is so much job competition out there. You can have another life and you can have it whenever you want it,” he explains.

Would his love of online games affect his willingness to work more? “I wouldn’t turn down the perfect job for it, but when looking for work I do consider the hours, preferring part-time as it gives me more time to do … other things.”

For Mark, gaming is his work.

“You’d be surprised how similar it [video gaming] is to a real job. As a guild leader, I have daily duties to attend to, disagreements to resolve and activities to organise for my team. If I don’t do a good job my guild could fall apart, so I feel a sense of duty to put in the hours to build and grow my team.

"This means you can’t be away from a keyboard for too long – so it does eat into your life.”

How much video gaming is too much?

There is no definitive cut-off point for what is an excessive amount of gaming, according to Dr Daniel Johnson, director of the Games Research and Interaction Design Lab at Queensland University of Technology, and author of 2013’s Videogames and Wellbeing: A Comprehensive Review.

“It depends on how you play, who you play with and whether gaming interferes with other aspects of your life. However, at around four to five hours per day you tend to see a spike in negative effects.”

These commonly include increased insomnia and anxiety.