Loading component...

At a glance

Within months of starting her job as a management associate at Citibank in Singapore, Violet Lim discovered something puzzling about her colleagues. Most of them were attractive, all of them seemed intelligent, so why were so many of them single? With Cupid tendencies and a mind for business, Lim quit her job in 2004 to start a dating company called Lunch Actually.

Fast-forward almost two decades, and Lunch Actually now employs a team of 75 full-time associates (known as “Cupids” and “Transformers”). The company has facilitated 120,000 dates across Singapore, Malaysia, Hong Kong and Jakarta, and 4500 of these have resulted in marriages and romantic partnerships. It has launched a dating app called LunchClick and recently unveiled Viola.AI, the world’s first dating marketplace driven by artificial intelligence (AI) on blockchain.

“Our big, hairy, audacious goal is to create one million happy marriages,” says Lim, acknowledging that this also presents a challenge to the business. “The more effective we are, the faster our customers are leaving us!” she says.

Modern romance

What may sound like a flawed business model has done little to limit the proliferation of dating brands, promising everything from lasting love to casual meet-ups.

The industry was given a boost with the launch of Tinder in 2012 – suddenly anyone with a smartphone could find a date – and the value of the global online dating market is expected to reach US$3.592 billion (A$4.7 billion) by the end of 2025.

The modern romance economy has seen huge changes since 1995, when Match.com became the first major dating site to register a domain. Today, it is part of the dating behemoth Match Group, which owns brands like Tinder, Hinge, OkCupid and Plenty of Fish. About 60 per cent of relationships that start on a dating site or app begin on a Match Group brand.

Dating companies monetise their offering in various ways. Membership subscription is the longest-standing model. The payments are typically recurring, and the model has a higher barrier to entry for use. Lunch Actually’s model, for instance, is based on customised membership packages.

Depending on a member’s needs and goals, their package may include a certain number of dates or relationship coaching sessions.

Bri Williams CPA, behavioural economist and managing director of consultancy People Patterns, says the subscription model aims to filter the calibre of members.

“The promise is that only those who are serious about love are going to put their money down, so the sites use money as a tangible indication of the quality of members,” she says. “Also, if you’re paying for the service, you’re likely to put more of yourself into it, and your expectations are going to be higher.”

The “freemium” model allows users to sign up to dating sites or apps and use the generated via advertising or by unlocking enhanced features for a fee. Sites like Hinge, for instance, charge users for unlimited daily matches. The site has an estimated six million monthly active users and about 400,000 subscribers.

“Sites that have a free offer have lowered the barriers to entry, because it’s a volume game,” says Williams. “They want to be able to say that your odds of success are higher, because the ‘pool of fish’ is much greater, but there are points at which they seek to monetise your involvement.”

Hinge is marketed as a site for serious relationships – its slogan is “The dating app designed to be deleted”. However, Mark Brooks, CEO of UK-based internet dating business consultancy Courtland Brooks, says dating apps get deleted both when they are successful and when they are not.

“Given the choice of the two, it’s better to be deleted because you’re successful, and then benefit from word of mouth,” he says.

Williams adds that even if users delete an app after finding their match, they may be likely to use it again if the relationship doesn’t go the distance.

“The beauty of these sites is that people don’t necessarily blame the service for any failings in a relationship,” she says. “By the time you’ve met someone and you think you’re falling in love, if it ends it’s either your fault or it’s their fault. By that stage, you’d rarely think it’s the fault of the dating site.”

Enter the love machines

The first attempt at computer dating took place back in 1959, when two Stanford University students used the institution’s IBM 650 to build a program that matched 49 men with 49 women.

While some sites, such as Lunch Actually, continue to conduct personal consultations with potential clients, most modern-day matchmakers are robots.

Dr David Tuffley, senior lecturer in applied ethics and cyber security at Griffith University, says the use of artificial intelligence adds a greater degree of precision to the matchmaking process.

"What dating sites are doing now is using AI for a much more granular getting-to-know-you process, so the person signing up becomes very well known in all sorts of personality dimensions."

“In the early days of online dating, people would fill out a questionnaire, and the company would try to match them up with someone, but people aren’t always entirely honest in questionnaires,” he says. “There’s a tendency to portray yourself in the most positive light.

“What dating sites are doing now is using AI for a much more granular getting-to-know-you process, so the person signing up becomes very well known in all sorts of personality dimensions.”

Match.com’s chatbot Lara, for instance, will have a conversation with you to help find singles with interests similar to your own. Apps like Badoo use facial recognition to suggest a partner that may look like your celebrity crush. Tuffley says some sites can even examine your public posts on social media platforms to gauge your attitudes and interests.

“There are certainly privacy issues around this, and the key thing is informed consent,” he says. “If a person gives their explicit permission to allow the company’s AI to look at their Facebook or LinkedIn pages, for instance, and they understand the implications of that, then that is considered ethical.”

“The problem is that this information is often buried in the terms and conditions, and people may not read them – they just click to show consent,” adds Tuffley. “This may be considered a rather disingenuous way of getting informed consent.”

Critical mass

There are thousands of dating apps on the market, but Brooks says there would be many more if it were easier for them to get onto app stores.

“App stores are a bit more restrictive these days, because they’ve recognised that there’s so many dating apps,” he says. “They’re not actually serving their users by loading up the chaff, and this is a good thing, because when users see a dating app on the first couple of pages of an app store, it’s generally going to be at critical mass.”

Gaining critical mass is the greatest challenge for any dating start-up, says Brooks.

“Essentially, they are ‘selling’ people to people, but when there is nothing to sell and nobody to interact with, it’s a black hole,” he says. “That’s why it’s very important for dating start-ups to come out of the gate running and to get to critical mass quickly.”

This is where “white labellers” come in – these are, essentially, dating companies that help anybody to start a dating website or app by sharing a common user database.

White Label Dating, for instance, is a leading off-the-shelf software-as-a-service business that gives other companies the tools to run their own online dating sites, including dating software, payment processing, customer support and a database of potential dating customers.

Imagine you have signed up to a dating site and have indicated that you enjoy golf. If the site is white labelled, your profile might then also appear on, say, Golfing Singles, if there were such as site.

This presents a number of privacy issues, says Brooks.

“When you sign up to a white label dating site, you might not know that it’s a white label site, but in fact it was all in the terms and conditions that you agreed to. It may look like your profile has been ported, but it hasn’t, because it is on a common database. It’s sitting in exactly the same spot – it’s just been displayed in multiple front ends.”

Safe space?

A March 2021 survey of 1000 members of the online dating industry by Global Dating Insights shows the biggest challenges facing dating apps are associated with safety.

This includes video and live-streaming safety, female user safety, scaling safety and more AI moderation. However, half of the respondents admit they could be doing more to protect their users from scammers and catfishing, and more than 63 per cent believe the risk of scams and fraud in online dating is on the rise.

Lim says that, while online dating is convenient, it presents its “own challenges, like no verification, fake profiles, scammers and people with dubious intentions”.

“Knowing this, we’ll be focusing on our strength and using technology to make that process more efficient,” she says.

“Technology has definitely grown exponentially and, in our industry, the mobile market is also a huge thing right now. At the end of the day, whether I like it or not, there will be new trends. I don’t see it as competition, but as opportunities for us to evolve and keep innovating.

“We’re also not just looking at the short term, because we aim to be a long-term business,” adds Lim. “There will always be new singles in the market.”

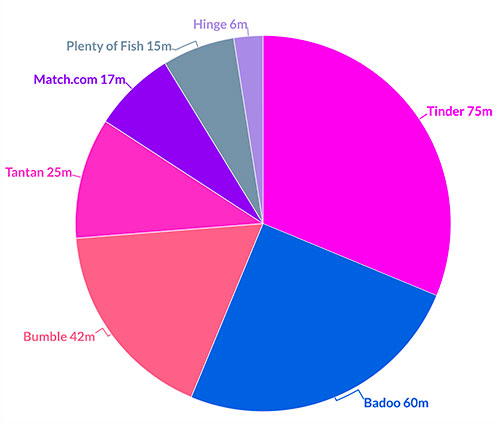

Global dating app market share

Dating on the blockchain

Trust is a vital ingredient of any long-term relationship. Enter Viola.AI, the world's first blockchain-powered dating and relationship AI tool.

Part of the Lunch Actually group of dating products, Viola.AI aims to engender trust and transparency in the dating industry. Its key feature is a verification process, known as REL-Registry, which is built on the blockchain and verifies user identity through visual recognition and social media checks. It also ascertains a user’s relationship status.

REL-Registry is complemented by the AI Love Adviser, which recommends relevant content, advice and services to meet user needs. Users can use the system’s own cryptocurrency to pay for membership services.

“Ultimately, our commitment is to create the most effective dating platforms for singles, and we realise that there is no one-size-fits-all approach,” says Lim. “That’s why, over the years, we have created different products like online dating platforms, dating apps and Viola.AI to help more singles.”

Global dating app users

2015 1.69 billion

2016 1.88 billion

2017 2.05 billion

2018 2.23 billion

2019 2.52 billion

2020 3.08 billion

Source: BusinessofApps

Global dating app revenue

2015 US$185 million

2016 US$200 million

2017 US$220 million

2018 US$235 million

2019 US$250 million

2020 US$270 million

Source: BusinessofApps