Loading component...

At a glance

- Blockchain was forecast to revolutionise financial services.

- Sceptics say it’s not delivering and question why there are so few blockchain projects in commercial use.

- Advocates say blockchain was at one point overhyped and now some of that is deflating, the technology is being used in areas such as supply chain management.

By David Walker

Blockchain was forecast to revolutionise industries ranging from financial services – currently its biggest claimed use – to shipping and asset logging.

Its biggest cheerleaders use language like technologist Don Tapscott’s declaration that “the internet is entering a second era that’s based on blockchain”; they declare that “there’s a whole new world coming”.

In recent months, however, a backlash has begun against blockchain technology. Critics point out that while uses can be imagined and demonstration solutions built, blockchain technology seems an unlikely answer to most problems.

Consulting group McKinsey brought some of this criticism into the open earlier this year when it published a report describing blockchain’s lack of real-world impact.

What's worth doing, and where blockchain's shortcomings are

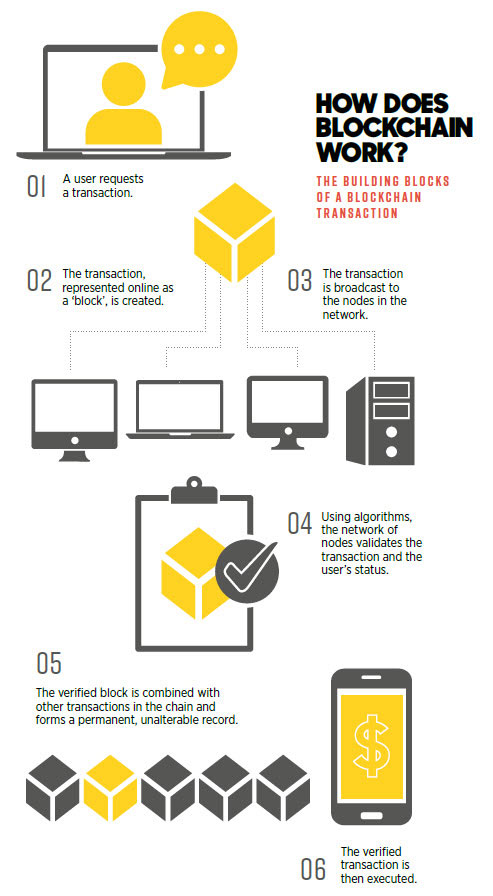

Blockchain technology allows records to be kept in what is often called a “ledger”, or a record of transactions. A blockchain ledger, however, has some unusual features: it is decentralised and distributed across various computers in a peer-to-peer network, with each record in the ledger time-stamped and cryptographically chained with the previous record.

This makes transactions in the blockchain ledger immutable or unchangeable. It’s not one new technology; it’s a combination of existing technologies – notably, cryptography and a mechanism for synchronising data across data stores.

Real money has been invested in blockchain technology, and by some of the world’s biggest companies – JP Morgan, Banco Santander and IBM among others. Blockchain is “an infant technology that is relatively unstable, expensive and complex,” to quote McKinsey, which has been true of other technologies that later became successful – including the relational database itself, today’s standard way to store data.

McKinsey and other sceptics argue that most of those features can be delivered by tweaking a traditional relational database so its records are encrypted, unalterable and distributed across multiple locations. Such a solution will typically be much faster than blockchain.

"I went looking for real actual production applications, and looked hard, and what I found was laughable.”

These critics query why so few applications have made it into action. By now, billions of dollars of investment and enormous enthusiasm should have produced some powerful, cost-effective applications besides illegal payments, they say.

Instead, the technology seems at the point where people produce example software that shows something can work. It’s producing relatively few examples of blockchain solutions that affordably perform worthwhile work.

Since blockchain has been identified as a potential solution for finance problems, its shortcomings have begun to emerge there first. The McKinsey authors, Matt Higginson, Marie-Claude Nadeau, and Kausik Rajgopal, say that many people working “at the blockchain coalface” have begun to have doubts, even as senior executives sing blockchain’s praises.

The authors argue there’s almost no situation where blockchain technology really works better than other technologies.

“There is a growing sense that blockchain is a poorly understood (and somewhat clunky) solution in search of a problem,” they write.

A consistent failing

McKinsey is not the only sceptic. When the Australian Government’s Digital Transformation Agency reported in February on how blockchain could help deliver government services, it described blockchain as an emerging technology with “gaps ... evident across both the technical and business facets of its implementation”.

Maria Bellmas, ANZ Bank’s associate director for trade and supply chain, has come to a similar conclusion. “The reality is a lot of the problems blockchain projects attempt to fix have already been solved by existing technologies,” she said in an article in March 2019.

“In many cases, a regular database can solve the problem with more reliability and for much less cost than blockchain,” she says.

Tim Bray is an Amazon technology leader, and co-creator of an important technology called XML, which once attracted a fair bit of hype of its own. He calls blockchain “an overpromoted niche sideshow”. He likes it as a concept, but sees none of the signs he’d expect from a technology taking off.

“If it’s actually generally useful, someone somewhere should be getting dramatically good returns on these investments, seeing hockey-stick revenue ramps,” he wrote in 2018. “I went looking for real actual production applications, and looked hard, and what I found was laughable.”

Bray tells INTHEBLACK that he stands by every word of his criticism. Other leading technology figures, including internet co-inventor Vint Cerf and security expert Bruce Schneier, have also argued that blockchain is overhyped.

Amazon reportedly spent time looking for cases where blockchain was the right solution, and eventually concluded blockchain did a superior job for clients in just one situation.

For clients who needed a verifiable log of transactions, Amazon has offered a database solution called QLDB with an unchangeable transaction log – achieving, for some purposes, the same end as blockchain through a better understood, higher-performance, more mature and reliable technology.

Where blockchain works

In some instances blockchain, for all its computational inefficiency, is the right tool for the job. Amazon’s research shows one slice of the market where it provides real value: a field it calls “secure decentralised transaction processing”. Some of the argument over blockchain’s future is about how important that slice will turn out to be.

Perhaps the single most watched blockchain project worldwide is the Australian Stock Exchange’s (ASX) project to replace the CHESS system that runs the Australian stock market. Built with the help of one of the world’s leading blockchain technology firms, Digital Asset, it was scheduled to start testing in April 2019 before a mid-2021 launch.

The leader of the ASX’s project, Cliff Richards, says he has no time for “the Silicon Valley cryptoanarchists and cypherpunks or the bitcoin lunatics”. He’s hoping that “the fascination, the attention and the hype” will now drain away from blockchain technology. Richards has to deliver a project, and he says the real issues with the technology are about the role of trust in business situations.

“There are many, many cases where blockchain should not be used,” he says. In such cases, conventional databases will do a better job.

“If trust is not a problem, you probably don’t need a blockchain. But where trust is an issue or a problem, distributed ledgers or blockchains in their various flavours ... can provide solutions for that.”

Richards argues that’s still a pretty big field. He says blockchain will provide meaningful benefits in industry verticals (where companies offer niche products or fit into niche industries) with supply chain problems, including trade services, capital markets and health care, where data is in multiple data stores and multiple formats and can benefit from being unified.

It’s particularly suitable in those cases where the various parties aren’t willing – or are not legally allowed – to let one party be the master of the data, and conventional database replication won’t work.

If the ASX was just replacing its traditional clearing and settlement functions, Richards says, a blockchain solution would have limited benefit.

Beyond those basic functions, there’s a big market in asset servicing, corporate action management, identity verification and other intermediary activities such as custodian activities and broking. If a major company makes a rights issue, it will be useful for different parties in that transaction to have rights to change data without reconciling that data to another database.

Richards says the ASX has found that the type of public, open blockchain used by bitcoin won’t work in regulated capital markets that need privacy and confidentiality. The ASX system will be initially accessible only by a small group. That will also eliminate one of blockchain’s greatest failings – speed.

Bitcoin can process about seven transactions a second; Richards says the ASX system can process 30,000 per second. To some, that makes it no longer a real blockchain. The ASX’s documentation refers mostly to “distributed ledger technology” rather than “blockchain”. The ASX system retains classic blockchain’s provable immutability, append-only log and cryptographic chain. In other words, it uses the technologies it needs.

Economising on trust

Chris Berg, economist and senior research fellow at RMIT’s blockchain hub, argues that blockchain’s critics miss its greatest strength: the way it economises on trust. In supply chain management, it can link multiple companies and regulatory agencies without the need for a trusted third party – “which is really hard to find in a global supply chain”.

Berg points to a couple of examples. Walmart has put all its leafy green suppliers on a blockchain-enabled system called the Walmart Food Traceability Initiative. Shipping line Maersk has developed a system called TradeLens, which also incorporates blockchain technology.

Both solutions were developed by IBM, which has invested heavily in becoming a blockchain technology leader. It’s not yet clear how important either of these solutions will be, but they are leading examples of working blockchain systems.

Richards agrees with at least some of the McKinsey trio’s criticisms. “Many people charged into the hype of blockchain,” he says. He is all too familiar with enthusiasts’ claims of it being “the solution to everything, including world hunger”.

Too few of the early blockchain builders understood their own business problems, he says. “Now that they’ve gone and built a blockchain solution or proof-of-concept, someone’s told them, ‘actually you could have done that cheaper, faster, better with a traditional solution’. Or they’ve tried to use a public blockchain in a situation where it can’t comply with regulations.

“Don’t let go of your scepticism,” Richards advises.