Loading component...

At a glance

- The global gamification market was valued at US$7.98 billion (A$10.5 billion) in 2019.

- Gamification has expanded far beyond the field of entertainment, and restrictions caused by the pandemic have given the industry an additional boost.

- Increasing adoption of gamification by businesses is expected to drive productivity, employee engagement and motivation.

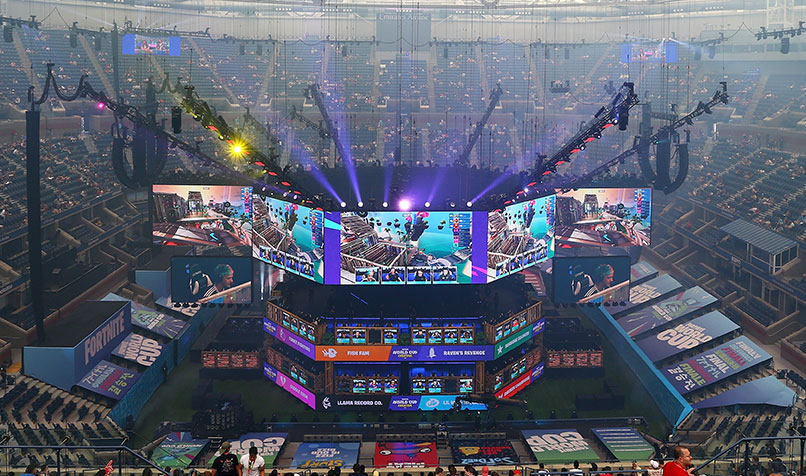

Professional gamer Richard Tyler “Ninja” Blevins, a cult hero with fans of online survival game Fortnite, pocketed a cool US$17 million (A$22.5 million) in prize money and endorsements in 2019 alone, putting him at the top of Forbes’ rankings of the top-earning gamers.

So much for the outdated stereotype of gaming being the preserve of tech geeks and school dropouts.

With games being used as remote learning tools and as part of business and marketing strategies for any number of sectors – including education, retail, healthcare, construction and defence – it would be trite to say that gamification has expanded beyond the realm of entertainment.

Take the phenomenally popular gaming platforms such as Roblox and Minecraft, for example, which are being used to help teach everything from the “Three Rs” – reading, writing and arithmetic – and languages to physics and politics.

The approach of introducing game-design elements into non-game applications to make them more fun and engaging is big business, too. In 2019, Mordor Intelligence put the value of the global gamification market at US$7.98 billion (A$10.5 billion).

COVID-19 boost

The COVID-19 pandemic has given the gaming industry an additional boost, as people turn to gaming to help pass the time in lockdown.

In the US alone, gaming sales rose by 37 per cent to August 2020 year-on-year, to US$3.3 billion (A$4.4 billion), according to market research firm NPD Group. In Australia, sales of gaming consoles soared by 285.6 per cent in a one-week period during March 2020 as the COVID-19 pandemic took hold.

Virtual reality (VR) is a branch of gaming that has been making firm inroads beyond entertainment.

Its use in fitness programs has been growing – for example, letting cyclists complete the Tour de France route virtually on a stationary bike, or giving runners a chance to sweat it out on the Boston Marathon course from the comfort of their own home.

The use of gaming technology is on the rise in the health sector as well, including as an aid for physical rehabilitation.

In Australia, a trial into the effects of digital devices in rehabilitation has found that the addition of VR video games, activity monitors and handheld computer devices to their usual rehab can significantly improve the chances of stroke patients, or those with brain injuries, being able to stand and walk.

Carried out at hospitals in Sydney and Adelaide and involving 300 participants ranging from 18 to 101 years of age, the study featured interactive exercises using gaming platforms such as Xbox and Wii, and let patients connect remotely with their physiotherapist via a Fitbit or iPad.

The study’s lead author Dr Leanne Hassett, from the Faculty of Medicine and Health at the University of Sydney, says trial participants had better mobility after three weeks – and again after six months – than those who completed traditional rehabilitation exercises.

Patients liked the cognitive and physical challenges of the games, and they had fun, so they typically exercised for longer and more often.

“A real challenge in rehab is getting people to do enough practice,” Hassett says.

“These games made a real difference.”

Effective teaching tool

Ron Curry, CEO of the Interactive Games and Entertainment Association, the peak body for the Australasian computer and video games industry, says educators in schools, universities and commercial settings are relishing the chance to use gamification on many fronts – for instance, surgeons play video games that simulate medical procedures, and heavy machinery drivers fine-tune their skills via video games.

“When you gamify something, it’s much easier for a person to look and see and feel how that’s happening, as opposed to trying to intellectually figure out what’s happening,” Curry says.

Early in his career, Stephen Allen, now a teaching fellow in the School of Business and Economics at the University of Tasmania, lamented that a traditional classroom-style approach to teaching finance skills did not seem to be working well.

Many students listened to lectures and promptly forgot what they had just heard. “I always asked myself, ‘In six months, are they going to remember these skills?’,” Allen says.

About 15 years ago, he started to gamify the lessons and today uses game simulation methods to teach everyone from Year 9 students to CEOs.

One of Allen’s greatest successes has been using a board game – in face-to-face and online forums – that builds skills and confidence in disadvantaged high school students.

The game requires students to work in teams as they run a hypothetical company in a fun, visual and competitive environment. Along the way, they learn how to produce and sell a product, while also acquiring leadership and team-building skills.

“Hopefully, by introducing them to these methodologies, like gamification, they’ll be encouraged to get a degree or a master’s degree,” Allen says.

“What I have discovered is that anyone who gamifies an approach and simulates an approach can engender deep learning.”

Addiction concerns

For all the positives of gamification, it can have a darker side. From around-the-clock gambling on smartphones to children getting hooked on their favourite games, there are certainly causes for concern.

Gamers can experience symptoms such as preoccupation with gaming, sadness and anxiety if gaming is taken away, and relying on games to relieve negative moods.

In the Journal of Behavioural Addictions in 2017, researchers reported “gaming disorder” prevalence rates of 10 per cent to 15 per cent among young people in several Asian countries, and of 1 per cent to 10 per cent among their counterparts in some Western countries.

"What I have discovered is that anyone who gamifies an approach and simulates an approach can engender deep learning."

“We’re not talking about a small number of people,” says Brad Marshall, a psychologist and author of The Tech Diet for Your Child & Teen, who helps families with children who have technology obsession issues.

While he dislikes the word “addiction”, Marshall agrees that gaming and excessive screen time can have negative effects on children aged 8 to 14 in particular, who are often not mature enough to manage their game and screen loads.

“It’s akin to stacking your house full of ice-cream and chocolate and sugar, and hoping that your 12-year-old child is just going to eat healthy stuff. They’re not going to do that.”

Young adults, and males especially, are also at greater risk of addiction. Marshall says the prefrontal cortex areas of the male brain that are responsible for emotion and impulse control do not fully develop until the mid-to-late 20s, so men can be susceptible to the lure of gaming.

Regulatory questions

One possible way to limit the impact of gaming is via strict regulation, but Marshall does not welcome an over-the-top response.

He notes that China represents the extreme end of the scale, where it has a country-wide rule requiring children to have an ID that allows them to access games. “I don’t think that something like that would ever be welcomed in Australia,” he says.

In Australia, a review of the computer game classification scheme is being conducted, with The Australia Institute think tank – among others – calling for R18+ ratings for some gambling-related games and stricter rules around the sale of online video games, including via mobile phone app stores.

For “overwhelmed” parents who do not know how to control the use of devices and the selection on online games and other digital platforms, Marshall favours parental tools that control wi-fi access and mobile data.

He has also called on tech companies such as mobile phone data providers, internet service providers and gaming and social media platforms to provide better options in this area.

“There are laughable security levels on some of these platforms, so you’ve got to ask how some of the smartest tech people in the world have made something so porous.”

According to Matt Harrison, a lecturer in learning intervention at the University of Melbourne, parents have to play their part in limiting access to potentially harmful games.

“I’m not giving kids Grand Theft Auto because those sorts of games are designed for adults,” he says in reference to the controversial game that has been accused of promoting misogyny and racism.

The key, he says, is to enjoy games in moderation. “There are people who are addicted, and they need help. That’s a health issue. But if a kid is playing games eight hours a day, that’s a welfare issue.”

Curry agrees and says health, welfare and addiction concerns need to be considered alongside the enormous benefits of gamification. “The technology is ethically neutral,” Curry says. “It’s how you apply it that is the key.”

Business outlook

As businesses increasingly adopt gamification in the years to come, the belief is that it will lead to better productivity, employee engagement and motivation.

Creating friendly competition and collaboration in a game-based setting can not only boost employees’ knowledge and skills, but also in turn lift the quality of service they provide to customers.

Hassett has no doubt that gaming technology will improve the remote delivery of care to some of the most vulnerable members of our society.

“That ability to be able to prescribe exercise and check on adherence remotely is going to be a real game changer for rehab,” she says.

For Curry, advances in virtual reality and augmented reality represent the next phase of gamification’s exciting evolution as a societal tool. If householders want to change a washer in a tap, for instance, a virtual plumber can stand beside them and provide step-by-step guidance.

“The technology is very exciting, and it’s only limited by our imagination,” Curry says.

Learning curve

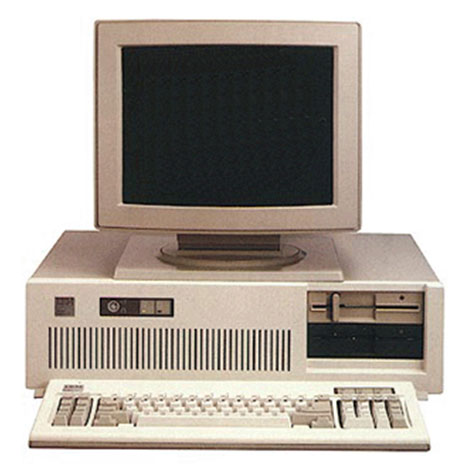

As a child in the 1990s, Matt Harrison had an IBM 286 desktop computer – a marvel for the time. Children from around the neighbourhood would descend on the Harrisons’ home to play games such as Castle Adventure and Commander Keen

“When I think back to how I developed skills like negotiation and turn-taking, a lot of that came from those early days of playing the computer with my brother and other kids,” says Matt Harrison, now a lecturer in learning intervention at the University of Melbourne.

Still a gamer and an app developer, he runs Next Level Social Skills, a community for neurodiverse children that uses cooperative video games to build confidence and social capabilities. The approach supersedes old methods such as role play, which Harrison says are “well meaning” but “stilted and artificial”.

The program targets children aged from 8 to 15, and is designed specifically to help children with autism, intellectual disabilities and ADHD.

Harrison says the embrace of gaming within the education sector is a far cry from the 1990s. Following congressional hearings in the US into violence in video games and their perceived impact on children, many teachers opted to steer clear of games as a learning tool.

The Columbine High School shooting in 1999 added to the caution after it was found that the two teenage perpetrators had spent a lot of time playing violent video games. “That had a really profound psychological effect on a lot of teachers,” Harrison says.

Today, he is confident that the synergies between the gaming industry and teaching can create genuine work opportunities for autistic children and others as they use games to build their negotiation skills and principles such as fairness.

“Gaming is a real area of strength for them, so it’s really exciting as a career option.”