Loading component...

At a glance

After years of teaching in the US, accounting instructor Debby Bloom spotted a business opportunity – to bring board games, also called tabletop games, to accounting education.

Bloom, who now works at Reading Area Community College in Pennsylvania, created Ledger Mania, a board game designed to make learning accounting fun.

First demonstrated at an American Accounting Association conference in 2009, Ledger Mania now features an online mode and eight different versions that cover the basics of accounting. Bloom says that, although games like Monopoly have a range of versions that could assist with accounting skills in theory, the underlying concept is at odds with what accountants actually do.

“The biggest issue is that the goal of Monopoly is to acquire wealth, which does not help students learn accounting. I created a game where you win by balancing the cash ledger and being a good accountant as opposed to winning by acquiring wealth.”

Money spinner

Bloom is not alone in embracing gaming culture. The popularity of card, tabletop, roleplaying and online games all surged during the pandemic.

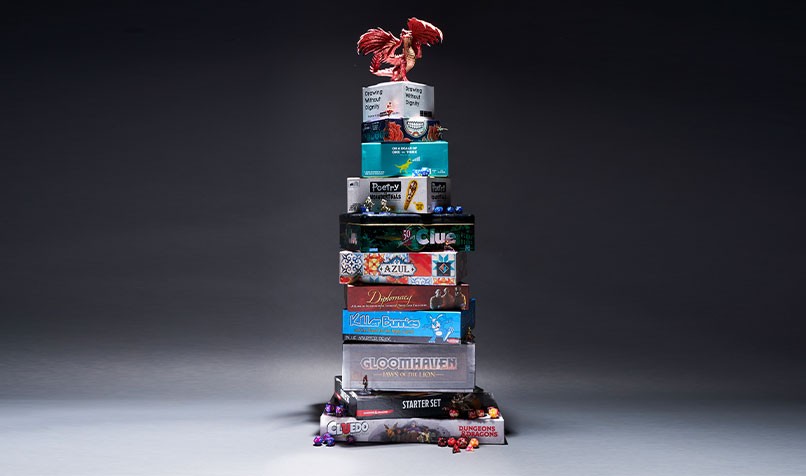

In addition to familiar favourites such as Cluedo, Scrabble and Trivial Pursuit, more complex, scenario-based games have also emerged. While the bestseller Wingspan relates to birdwatching, other games feature werewolves, zombies or Vikings, or are set in space or medieval worlds. The popularity of roleplaying game Dungeons & Dragons soared when it featured prominently in the Netflix hit series Stranger Things.

The global board game market is valued at between US$11 billion (A$16.4 billion) and US$13.4 billion (A$20 billion), according to market research companies Technavio and IMARC. It is projected to grow by up to 11 per cent during the next five years on the back of interest from millennials, as well as parents looking for screen-free entertainment alternatives for the family.

"Engaging in play allows you to interact with your peers in a different way, but also with the learning material in a different way, so you can tinker and explore and get excited about a project as opposed to just looking at it mechanically and analytically."

Boardgames Australia chair Matthew Utting says the social appeal of games reignited during the pandemic.

While the pandemic initially inhibited the ability to play games in-person, the rapid growth of online games and single-play gaming added another exciting element to the industry, Utting says. Meanwhile, online board game platforms such as Board Game Arena, Tabletopia and Tabletop Simulator provide gamers with access to thousands of games.

“A lot of people moved to solo or single-play gaming during COVID-19. There’s almost an expectation that games will have a solo mode now, and we’re also seeing a pick-up of people coming back to in-person gaming after the pandemic. I think the audience will continue to grow,” Utting says.

Beyond entertainment

Board games are increasingly being used as training tools for businesses and as therapeutic release for people struggling with social and mental health issues.

Seattle-based therapeutic game master Adam Davis is the co-founder of not‑for‑profit Game to Grow. The company adapts games such as Dungeons & Dragons and Minecraft to help struggling young people become more confident, creative and socially capable. Game to Grow is operating in a fast-growing space that includes Geek Therapeutics and The Bodhana Group in the US and Game Therapy in the UK.

Davis says that games have been crucial to providing social interaction, without pressure, for those experiencing a heightened sense of isolation and loneliness during the pandemic.

“It’s something in our DNA – the need to gather around and sit in circles and make meaning,” he says.

Soft skills boost

Davis has no doubt that the therapeutic benefits of gaming translate to the corporate world, where qualities such as emotion regulation, collaboration and the ability to have perspective are highly valued.

Just as improvisation activities have been used successfully to engage workers, Davis says true play can help to reduce stress and peer tensions in the workplace and take the emphasis off key performance indicators, deliverables and “the focus on being perfect”.

"Negotiation is a big thing. Some games have negotiations where you’re trying to get deals across the line, so it’s often those soft skills that emerge in games."

“The games are not the point – the play is the point,” Davis says. “Engaging in play allows you to interact with your peers in a different way, but also with the learning material in a different way, so you can tinker and explore and get excited about a project, as opposed to just looking at it mechanically and analytically.”

Utting believes that, in addition to building social confidence, game-playing can boost the soft skills that businesses crave – the ability to think, problem-solve, negotiate, cooperate and use deductive reasoning.

“Negotiation is a big thing,” Utting says. “Some games have negotiations where you’re trying to get deals across the line, so it’s often those soft skills that emerge in games.”

A new way to teach

Incorporating game play into the learning environment can increase engagement and encourage equal participation from students.

Dr Melissa Rogerson, computing and information systems lecturer at the University of Melbourne, says there is a large and growing market for games that can be used for training and education in business settings. The key will be to improve the quality of this kind of game.

“As someone who loves playing games, I’ve tended to be quite sceptical, because a lot of those games are just not very good. What I’ve also realised, though, is that maybe it doesn’t matter if the game’s not great. It’s still a more approachable, interesting and engaging way to learn and to build memorable moments.”

Rogerson says it is important for a game to foster “meaningful play”, creating a sense that people are playing for a reason, such as to learn. Games that keep play interesting also tend to balance luck and skill, she adds.

While chess is about skill, a game like Ludo tends to come down to the roll of the dice.

“A game that keeps people involved and engaged is really important, and that can be an issue with games that are pure skill – people already feel that they’ve lost, so there’s no need to stay engaged,” Rogerson explains.

Bloom says a sense of creativity and investigation is important for accountants, both at student and professional level. She has observed that traditional instruction methods can encourage “social loafing” – a phenomenon where a person exerts less effort to achieve a goal when working in a group rather than alone.

“What would happen is all the students would get basically the same problem sets, so if you just claim, ‘I don’t know’ long enough, your neighbour or teacher will give you the answer,” says Bloom.

As to the future for Ledger Mania, Bloom expects expansion will hinge on being able to deliver different versions of the game and address a broader range of accounting tasks.

“For example, it could be used to teach industry-specific accounting, and that’s why I see some growth potential in the training market,” she says.

Davis’s goal with Game to Grow is not particularly financially driven, but he is keen to maximise the reach of its games programs and extend their impact into facilities such as libraries and prisons, where people “can go play and be safe”.

While Davis expects online gaming to continue to thrive, he does not think in‑person gaming will suffer as a result.

On the contrary, there are real benefits to be “looking someone in their real eyes and sharing physical space with people”, he says. “I’m still a big defender of the human experience outside any virtual world.”

Whatever the idea or the format, Utting believes there will be no shortage of businesses and entrepreneurs seeking to come up with new and different board game concepts.

“There’s always someone trying to get the next big thing,” Utting says.

Crowdfunding success

Crowdfunding is making it easier for budding designers to release games and tap into a niche market. For those who get the game right, there is significant money to be made.

An early example of this is the remarkable success of Exploding Kittens, in which the point of the game is to avoid drawing an exploding kitten card. After initially seeking to raise US$10,000 (A$15,000) through popular crowdfunding platform Kickstarter in 2015, the game raised almost US$9 million (A$13.5 million) in a month, and The Exploding Kittens Company has gone on to sell millions of games.

The Kickstarter campaign for critically acclaimed “dungeon crawler” game Gloomhaven raised US$386,104 (A$577,322) from its initial US$70,000 (A$105,000) goal, and US$4 million (A$6 million) more for its second printing.

Cepholair Games, the makers of Gloomhaven, launched a Kickstarter campaign for its sequel, Frosthaven. That campaign ultimately raised US$13 million (A$19.4 million) from its US$500,000 (A$748,000) goal, making it the highest funded board gaming project on Kickstarter.

A rewards-based campaign provides an incentive for would-be backers. This means a reward is offered in return for the money pledged. Many board game campaigns offer potential players with an early copy of the finished game.

The crowdfunding campaign for Gloomhaven was so successful that it led to expansions and sequels, including Gloomhaven: Jaws of the Lion (above) and Frosthaven

Board games for accountants

- Accounting for Empires can be played solo or in teams. Players score points and expand their empire as they answer exam‑style questions.

- Ledger Mania is a board game and an online game. It “gamifies” the principles of accounting posting, journalising and closing. Different scenarios teach different skills, from high school-level to intermediate accounting principles.

- Bank On It is an online game designed to challenge players on accounting fundamentals as they navigate business scenarios and answer questions inspired by content from accounting textbooks.

- Diplomacy is ideal for risk managers. Players use negotiation skills instead of dice as they control armies and resources to forge alliances and overcome enemies.

- Acquire is similar to Monopoly, but is more tactical and less reliant on luck. Players invest in real estate, acquire wealth and reinvest in shares and a range of other business ventures.

- Globalization focuses on business expansion as players seek to build a financial empire worth US$1 billion (A$1.5 billion). Along the way they deal with IPOs, paying expenses and accumulating interest on debts.

What makes a good game?

Few can match University of Melbourne lecturer Dr Melissa Rogerson when it comes to a love of board games – she and her husband collectively own more than 1500 games. In her game studies and human-computer interaction research, Rogerson has identified four recurrent aspects of gaming that players value:

- The social experience brings people together around a table, with a shared focus, often as an excuse to catch up.

- Variety gives players the option of picking a different game each time they play.

- The intellectual challenge requires players to develop plans, problem solve, make decisions and strategise.

- Materiality means players can touch and rearrange game pieces.