Loading component...

At a glance

By Johanna Leggatt

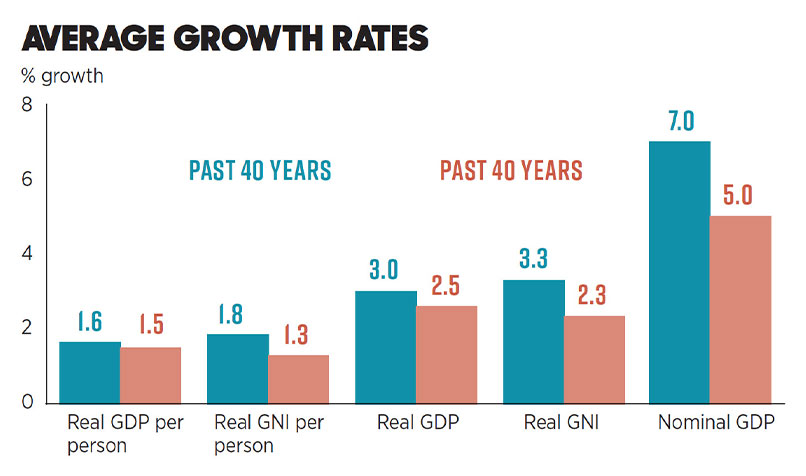

There were very few surprises in the Australian Government’s latest Intergenerational Report (IGR), but nevertheless, the overall tenor was sobering – a budget in the red until mid-2050, the increased costs of an ageing population, and the general uncertainty posed by the post-pandemic world.

As the report notes, referring to the pandemic, “While Australia’s economic recovery is well advanced, some effects from this shock will persist for years to come”.

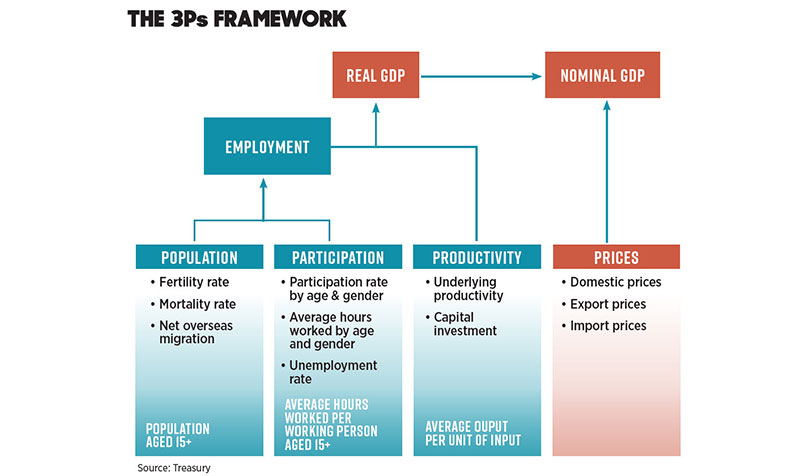

The most recent IGR, which was delayed by a year owing to COVID-19, outlines expectations of economic growth in the next 40 years across key economic drivers of growth – including the “three Ps” of population, participation and productivity.

The report finds that, while Australia’s population has been increasing, it is at a slower rate, and workplace participation, while currently high, is expected to decline. Productivity, meanwhile, is already slowing in line with global trends, with the report noting that “Australian firms appear to be slower to adopt world-leading technologies”.

How concerned should we be about this slower pace of growth? What, if anything, can be done about it?

Fewer people to tax

Australia’s population has grown at an annual average rate of 1.4 per cent over the past 40 years, but for the first time in an Intergenerational Report, Australia’s population projection has been revised down to 0.8 per cent growth per year by 2060-2061.

Sarah Hunter, chief Australia economist at BIS Oxford Economics, views this declining rate of population growth as “almost inevitable”.

“It’s partly a product of social changes, with women having fewer children, and an ageing population,” she says.

“It does mean slower growth for the economy, notwithstanding what might happen to productivity.”

Funding the healthcare needs of an ageing population has long been a concern for government, and Hunter sees this concern intensifying as the tax base continues to shrink.

“There are questions we have to answer as a society, and I use the term ‘society’ quite deliberately, because some of these health costs will be co-funded by people through their superannuation and private health insurance,” Hunter says.

“The question that will only get bigger is, how much burden should be placed on the individual?”

Fabrizio Carmignani, professor of economics at Griffith University in Queensland, says that, while population growth trends are important, we shouldn’t overestimate their relevance for the Australian economy.

“Population growth is known to be a possible driver of aggregate economic growth, but what we are interested in is the growth of GDP per capita, because it’s GDP that is correlated with wellbeing and human development,” he says.

“Population growth does not necessarily have a positive relationship statistically with the growth of GDP per capita, so I personally don’t want to overestimate its role.”

Boosting participation

There are similar trends at play with workplace participation, which has increased over the past 40 years to reach record high levels of 66.3 per cent in March 2021. However, the report reveals that the participation rate is expected to decline to 63.6 per cent by 2060-2061, “as the proportion of older Australians in the population increases”.

Hunter, however, argues there are many levers that the government and the private sector can pull to ensure greater workforce participation over the coming decades, including removing barriers for women to return to work, flexible workplace arrangements, and incorporating new technologies.

A key strategy is helping older people stay in employment longer, including shift work, remote work and job sharing.

“There are businesses with quite large labour forces who are a bit older, where they’re able to efficiently and effectively make it work,” Hunter says.

"Productivity is linked to new discoveries, and so I don't want to sound pessimistic, but in order to increase productivity, we need another industrial revolution."

“If you can place these employees in a role that means they can be productive, or that they can job share effectively, then the business wins, too.”

Carmignani says participation should be encouraged through active labour market policies that help both the unemployed and the underemployed. “We need to ensure, for instance, that there is workplace flexibility for female workers to participate more in the labour force,” he says. He also advocates for greater investment in job-matching programs that connect people to opportunities in other sectors, as well as re-skilling courses.

“Re-skilling is not just the role of government, but it’s vital for the private sector as well,” he says. “Companies gain a lot from re-skilling a new employee, as it becomes an investment rather than a cost.”

Carmignani also views participation through the same lens as population data – illuminating, but not the lynchpin that will make or break economic growth over the next four decades.

The productivity mantra

What does have the potential to make or break economic growth, however, is productivity – the level of technological innovation, progress, wage growth and healthy levels of competition that accelerate growth.

Unfortunately, as Hunter points out, the past decade has witnessed disappointing productivity rates both in Australia and overseas, with labour productivity gains slowing since about 2005 and averaging 1.2 per cent annually in Australia, as compared to the historical average of 1.5 per cent.

“It’s not that we haven’t had technological advances, but the rate that they’ve come through at and the impact they’ve had in terms of output have not been as fast as before,” Hunter says.

“It’s been said that technology improvements are increasingly improving our leisure life, such as the Netflix model, but perhaps having less of a tangible impact on our business life.”

Post-pandemic, Hunter cautions against Australia maintaining a “fortress mentality” in its business dealings, as this could have a detrimental impact on productivity.

“From a GDP perspective, we need to interact with the rest of the world, as learning from how others do business and innovate has a huge impact on productivity,” she says.

The Australian Government must also work to enable private companies to make good use of technology in certain sectors, such as energy and digital communications.

“For example, in Australia, we have a problem with energy policy, because there is very little certainty for firms,” she says.

“When you talk to operators on the ground, it’s causing problems because they might have a renewable technology that is very efficient, but because the policy framework isn’t clear, Australia is not in an optimal place to encourage the private sector to invest and investigate these new technologies.”

A new industrial revolution?

Productivity is so crucial to a nation’s future fortunes that Carmignani argues that what is required is a new industrial revolution.

The most recent was the IT revolution that began in the 1960s, he says, but its impact is slowly ebbing.

“Now, that might sound controversial when it appears that every day you have a new kind of iPhone appearing, but these new things are evolutionary in nature, not revolutionary,” he says.

“Productivity is linked to new discoveries, and so I don’t want to sound pessimistic, but in order to increase productivity, we need another industrial revolution.”

Where is the next industrial revolution likely to emerge? “The answer, I believe, is a green technology revolution that boosts productivity growth and economic growth,” Carmignani says. “The first step in this process is a scientific breakthrough, and then entrepreneurs see the commercial potential from the discovery you’re bringing into the economy, and the process takes off.”

It’s important, however, to not try to “pick a winner” and fund one sector only, Carmignani warns.

“There is a temptation for governments to decide that the next big wave of innovation will happen in a particular area,” he says.

“Green technology, for example, could be developed across a multitude of sectors – it doesn’t need to be solar panelling or electric cars, it could be in bio-medics.”

Either way, he argues Australia needs to use government money, via tax exemptions or other forms of support, to fund ideas tied to specific milestones.

“That way, we can track the extent to which these ideas grow into real innovation,” he says.

If a new industrial revolution stalls, then there could be real consequences for the Australian economy.

“You project the current trend over the next two or three decades, and you go back to zero growth,” Carmignani says.

However, there is a positive note to Carmignani’s “Armageddon-like” scenario of the decline in the IT revolution, and it is this – this is not the first time that a wave of industrial revolution has come to an end.

“It happened with the first Industrial Revolution, and then a second one came along,” he says.

“So, in the past 300 years, we have always been able to, at some point, generate the next wave of growth.”

Productivity assumptions and oversights

All intergenerational reports contain assumptions, and if you ask Rafal Chomik, senior research fellow at the ARC Centre of Excellence in population ageing research, the latest IGR is no different.

Chief among the most glaring assumptions, Chomik says, is the report’s assertion that annual productivity growth for the next 40 years is based on the average of the last 30 years of 1.5 per cent. “In the 1990s, growth was 2.2 per cent annual over the decade, in 2001 it was 1.4, and in 2010 it was 1 per cent, and yet the IGR expects it to go up to 1.5 per cent,” he says.

“So, it is potentially overly optimistic, given the trend we’ve seen over the last few decades, and it’s probably the assumption that has the biggest effect on things like income and GDP growth and therefore the tax take.”

Traditionally, Chomik says, governments have looked to big economic reforms to stimulate productivity, such as floating the dollar, introducing the GST and establishing the independence of the Australian Reserve Bank.

“The Treasurer [Josh Frydenberg] himself said that we cannot float the dollar twice,” Chomik says. “So, there is a kind of acknowledgment within the government that those low-hanging fruit of the 1990s are largely gone.”

Chomik notes, however, that a landmark review by the Productivity Commission in 2017 spelled out a range of micro-economic reforms across a five-year period.

“There has been no indication by Frydenberg that the government intends to ask the Productivity Commission to complete another five-year plan to look at the structural reforms and government service delivery improvements that the Productivity Commission could advise on,” he says. “But that is something they could ask them to do now.”

Furthermore, Chomik says that, despite the threat of climate change, the report does not offer any number modelling on its potential economic impact.

“Climate change could affect the economy in different ways – it could mean that some of our products are not being sold at the prices that we might expect, or the adaptation itself could be costly in making sure that there is resilience against climate-related events,” he says.

“If you are talking about sustainability over the next 40 years, then the admission [of the specific climate modelling] is the elephant in the room.”