Loading component...

At a glance

- Australian gig economy workers are set to benefit as new protections roll out, spurred on by a Fair Work Commission finding.

- To date, gig workers have been typically classed as independent contractors, leaving them without the rights of regular employees and leaving them vulnerable to exploitation.

- The economy’s growing dependence on gig workers signals that the gig economy is here to stay.

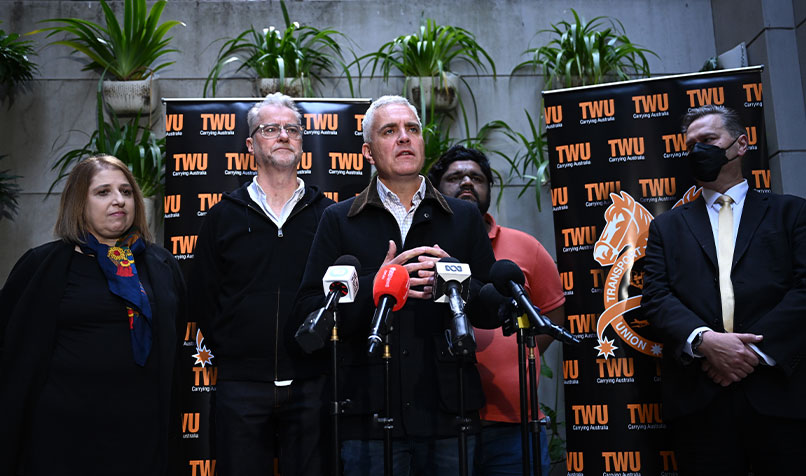

In May 2022, food delivery platform DoorDash and the Australian Transport Workers’ Union (TWU) signed a landmark agreement that may lead to minimum rights and conditions for its gig economy workers.

This agreement was the first of its kind in Australia, but it follows other recent wins for gig workers. These include a Fair Work Commission finding that riders directly engaged by Menulog should be covered by the Road Transport and Distribution Award 2020, thereby giving them basic employment rights.

The Labor government has also promised to give the Fair Work Commission powers to set minimum pay and conditions for gig workers and other “employee-like” workers, which it outlined in its Secure Australian Jobs Plan.

These are all positive steps towards improving workers’ rights in the gig economy, which has long been a contentious issue.

Gig workers are often classed as independent contractors, which means because they are not employed on a formal or full-time basis, they don’t have the rights and protections that regular employees have, such as the right to paid leave or protection from unfair dismissal.

Unions have been arguing the case for basic rights for gig workers for years, since the term first started appearing in the mid-2000s.

“Whether it is students, retirees, parents or small business people, work through apps like DoorDash appeals to many, because it can fit around their lives and other commitments.

That’s why we commenced conversations with the TWU, who have decades of experience advocating for Australian workers including independent contractors,” says Rebecca Burrows, general manager of DoorDash Australia and New Zealand.

“Years of neglect by the former government have opened the floodgates to terrible exploitation in the gig economy.

Work has been deliberately structured in such a way so as to deny gig workers the rights and entitlements many Australians take for granted, like protection from unfair dismissal, sick leave and superannuation,” says Michael Kaine, national secretary of the TWU.

“As a result, workers are loaded up with extraordinary pressure to work long hours, cut corners and rush to make ends meet. Horrific injuries and shocking deaths are all too common.”

This was the catalyst for Menulog, which, after a series of deaths in the broader transport industry and pressure from unions, announced it wanted to employ many of its riders, rather than classify them as independent contractors.

As employees, Menulog’s drivers are now covered under the Road Transport and Distribution Award 2020.

What do these developments mean for the gig economy, and the economy more broadly? With other platforms following in DoorDash’s footsteps, and Menulog challenging the inherent flexible employment model, will better protection for workers mean a stronger economy?

Riding the wave

As of December 2020, approximately 250,000 Australians were part of the gig economy – and this number includes many who perform these tasks in addition to another job.

It’s a figure that keeps rising, and the economy’s growing dependence on gig workers means the issue of labour exploitation won’t go away.

There is rising awareness of how environmental, social and governance (ESG) factors and trends influence the financial performance of a business.

Many businesses are becoming more transparent about their operations, highlighting their green credentials and promoting their diversity policies, for example.

The “S” in ESG looks at how an organisation maintains positive relationships with suppliers, customers, employees and the communities it operates in, as well as how it manages the risks of negative impacts on these groups.

In practice, this can include providing safe and healthy working conditions for employees, as well as ensuring labour standards across the supply chain that guarantee fair wages and human rights protection.

"Workers are loaded up with extraordinary pressure to work long hours, cut corners and rush to make ends meet. Horrific injuries and shocking deaths are all too common."

Yet, recognising a dependency on using gig workers or platforms that don’t offer rights to gig workers has yet to hit the ESG radar of many businesses.

“The gig economy is currently on the margins of the ESG agenda, but is rising in prominence,” says Adam Carrel, partner, climate change and sustainability services at EY.

“Investors, in particular, are highly focused on modern slavery. But this is maturing into a broader interest and concern regarding labour exploitation in general, both as a moral concern, but also as an indicator of a business model or assets that might be stranded by a substantial change to the recognition of gig workers and their entitlement to expanded labour.”

While consumers also hold some power in influencing business success, they are yet to add an authoritative voice to the conversation around better protection of workers.

“As yet... the consumer does not appear to be a vocal agitator for change. There is mounting cynicism towards the notion that the gig economy is a technology-enabled source of flexible opportunistic work.

The gig economy is functioning like all new ‘boom’ economies in that it starts by writing its own rules, but is ultimately encircled by social norms and regulations that hold it to a higher account,” says Carrel.

Change is coming

The DoorDash agreement is a step forward for workers’ rights and, through an independent body, aims to “provide standards, protections and access to benefits, without sacrificing the autonomy and flexibility independent workers value”, says Burrows.

“The agreement calls for the creation of a national framework that would allow app-based workers to maintain their independence, while accessing new protections and benefits tailored to this new form of work.

“For platform businesses, this would enable business certainty and a level playing field,” she says.

“After several months of dialogue, DoorDash agreed on an industry-leading joint set of principles with the TWU. We are pleased to see that since then, other industry participants have made similar commitments, which shows that consensus is building,” says Burrows.

In fact, the DoorDash deal was reached just weeks before rideshare and food delivery competitor Uber agreed to a similar arrangement with the TWU.

Dara Khosrowshahi, Uber global CEO, told the media at the time, “This deal is about raising up the voice of independent workers and focusing on what they say is most important to them – flexibility and control over when and where they work, earning a fair wage and access to benefits and protections.”

Economic impact

Gig work has given many people a vital source of income through the economic hardship caused by the closure of businesses due to continued lockdowns, and it contributes A$6.3 billion to the Australian economy.

However, it’s not just rideshare and food delivery platforms that make up the gig economy.

The gig economy started growing in popularity in 2008-2009 when the global financial crisis forced many individuals to resort to task-based labour.

Many people assume that gig jobs are for lower-income or lower-skilled workers; however, gig work covers a huge range of activities.

This includes anyone looking to supplement their household income or shift entirely away from the day-to-day grind of office work.

"This deal is about raising up the voice of independent workers and focusing on what they say is most important to them - flexibility and control over when and where they work, earning a fair wage and access to benefits and protections."

For all its negative effects, COVID-19 gave many people an opportunity to shake things up and change the way they live and work.

Now, as offices invite people back in again, the temptation to be their own boss and determine how much and what kind of work they want to do is driving many people’s new career path.

In addition to DoorDash drivers and Airtaskers, people are turning to short-term gigs, done from their own home, on their own terms.

Gartner reports that 32 per cent of organisations have been replacing full-time employees with contingent workers for increased flexibility and as a cost-saving measure since the onset of COVID-19.

It has also raised the question for HR managers to consider how performance management systems apply to contingent workers, as well as whether they are eligible for the same benefits as full-time workers.

Into the future

For Michael Kaine, national secretary of the TWU, the agreements reached with DoorDash and Uber draw a line in the sand and are a step towards creating a sustainable gig economy for transport workers.

“At their core, both agreements recognise that an independent body to establish universal standards for earnings, flexibility, safety and security for all workers is essential to improve the gig economy into the future,” he says.

“Such a body must be empowered to recognise the arbitrary labels of employee or contractor are simply outdated, and instead examine issues like levels of dependency in the process of setting appropriate standards,” he says.

It also makes good economic sense, argues Adam Carrel, partner, climate change and sustainability services at EY.

“Any business model that relies on distinct imbalances of power is ultimately on an unsustainable footing, so the introduction of better worker protections will potentially weed out flawed business models, but this will ultimately be to the benefit of the economy as a whole,” says Carrel.

Kaine agrees: “Creating a gig economy that’s safer, more sustainable and less volatile is in all our interests.”