Loading component...

At a glance

- The Parliamentary Joint Committee has proposed recommendations aimed at boosting confidence in audit quality.

- The greatest impact on entities and auditors is likely to be the proposal for mandatory audit tendering, internal controls reporting and assurance.

The Australian Parliamentary Joint Committee’s (PJC) final report on its inquiry into the regulation of auditing has been postponed until December to allow time for further hearings and consideration of the evidence, and due to the restrictions imposed by the COVID-19 pandemic.

The PJC’s interim recommendations, issued in February 2020, are far-ranging.

They encompass the Australian Securities and Investments Commission’s (ASIC) audit inspection program, fees for non-audit services (NAS), audit tenure, digital financial reporting and the scope of both the audit and the entities’ reporting.

These recommendations have been widely welcomed as measured and balanced, but do they go far enough in providing confidence in audit quality and in turn confidence in the quality of financial reports to support well-informed capital markets?

The greatest impact on entities and auditors is likely to come from the proposals to introduce mandatory audit tendering and internal controls reporting coupled with assurance, similar to the internal controls for financial reporting introduced in the US under the Sarbanes-Oxley Act (SOX) of 2002.

This regime was in direct response to the Enron and WorldCom collapses, and applies only to publicly traded companies and their subsidiaries.

CPA Australia notes in its submission to the inquiry that “there is a lack of evidence to support the notion that audit firm rotation improves audit quality”.

Nevertheless, it suggests encouraging periodic, possibly 10-yearly, audit tendering through a best-practice approach.

The PJC has gone further by recommending mandatory 10-year audit tendering. This may have a significant impact on the audit market, since the majority of ASX 300 audits have already been conducted by the same audit firm in excess of 10 years.

However, the PJC’s recommendation for tendering on an “if not, why not” basis will help to reduce any adverse impacts.

If the PJC’s recommendations were to be adopted, the entities they would apply to need to be considered carefully. Implementation must also be staged appropriately to avoid overburdening smaller entities or creating outcomes that compromise competition.

The UK Government has been grappling with audit quality concerns following a series of high-profile corporate collapses.

Sir Donald Brydon’s independent review into the quality and effectiveness of audit in the UK put forth 62 far-reaching proposals that will be critical to restoring confidence in audit and, more importantly, paving the way for more effective corporate governance and oversight.

Brydon’s recommendations for holistic reforms, which consider the entire corporate reporting supply chain rather than focusing on audit in isolation, hold many potential lessons for Australian policymakers.

Opportunity to be proactive

Over the past several years, corporate failures in the UK, including Carillion, Patisserie Valerie and Thomas Cook, have resulted in four separate government inquiries, including Brydon.

Australia faced a similar situation in 2001, when a rash of collapses – including HIH Insurance, One.Tel and Ansett – triggered the Royal Commission into HIH Insurance and Professor Ian Ramsay’s report, Independence of Australian Company Auditors.

This resulted in the establishment of the ASX Corporate Governance Council in 2002, as well as the CLERP 9 regulatory reforms in 2004, which introduced conflict-of-interest prohibitions, auditor rotation requirements, independence declarations and NAS disclosures for auditors.

While Australia’s recent track record with respect to corporate failures has been much better than the UK’s, the hearings of the PJC inquiry have been, at times, very critical of the conduct of auditors.

Concerns raised are largely based on questions about the adequacy of auditors’ independence, competition and persistently poor audit inspection findings reported by the Australian Securities and Investments Commission’s (ASIC).

The PJC inquiry is an opportunity for Australia to take a proactive approach by introducing preventative measures to avert future corporate failures and fraud, balanced against the cost of such measures.

Brydon vs PJC

One of the most significant reforms proposed by Brydon is expanding directors’ responsibilities to encompass risk and internal controls, including new obligations for fraud detection.

However, Brydon recommends that internal controls reports be audited on an exceptions basis only.

Brydon recommends an expansion of the scope of the auditor’s report in some areas, including prior reporting deficiencies, transparency over estimates, key performance indicators (KPIs) and risk signals, which the auditor should not restrict to information that has already been reported by the company.

Since the auditor has always been restricted to not introducing new information, this would be a significant shift in the auditor’s role. The PJC has not recommended such a shift thus far, and doing so may create new risks for the auditor.

Brydon suggests that the need for information to be audited should be left to the market in a number of areas.

While the PJC inquiry has not made a recommendation in this area yet, CPA Australia’s submission to the inquiry suggests that, rather than leaving it to the market, the entire annual report should be audited or assured, and any unaudited information be reported by other means.

Arguably, this would offer greater confidence in the annual report and clarity about what has been audited or assured.

As a result, business strategies, future prospects and material business risks in the directors’ report, including for listed entities the operating and financial review, would require assurance, which would focus attention on the reasonableness of the underlying assumptions and the data relied upon.

CPA Australia's contribution

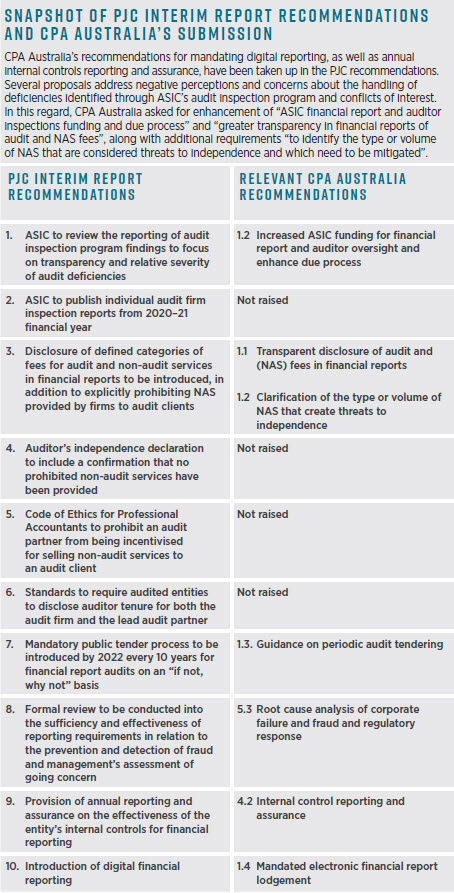

CPA Australia’s submission to the PJC inquiry recommends a series of reforms, many of which were reiterated in the public hearings and the most critical of which were included in the PJC’s interim report recommendations.

Of the 10 recommendations put forward by PJC, four were proposed by CPA Australia directly, and two were raised with some differences in suggested responses.

In its submission to the inquiry, CPA Australia has called for “the conduct of a root-cause analysis of corporate failure and fraud as a basis for designing a regulatory response”, as this is an area that could offer tangible benefits in prevention of fraud and unexpected corporate collapse.

This is reflected in the PJC recommendations to review going concern assessments and reporting requirements’ effectiveness for fraud prevention and detection.

Mandating digital lodgement of financial reports, which CPA Australia considers to be long overdue, has also been recommended by the PJC. Implementation may need to be staged or restricted to public interest entities, at least initially.

ASIC has had the capacity to receive digital reports for many years, but entities have simply not lodged them.

Easily – and preferably freely – accessible, digital financial reports would support well-informed capital markets.

What is the way forward?

While the reforms proposed in the PJC’s interim report may seem relatively measured and achievable, they are nevertheless likely to have a significant impact on entities and their auditors if they are taken up by the government.

The Brydon Review contains a multitude of reforms, many of which are innovative and could have significant positive impacts, but equally may be disruptive and costly.

Monitoring the UK’s progress in responding to the Brydon Review will enable Australia to identify possible regulatory solutions for local issues.

The time is ripe for the consideration of change in audit, but priority outcomes, addressing clearly identified problems and issues, need to drive the focus of any reforms in Australia.

Claire Grayston FCPA was CPA Australia’s policy adviser - audit and assurance

CPA Australia resource:

The benefits of Sox Controls Reporting have outweighed the costs

Len Jui FCPA, who was previously associate chief accountant at the US Securities and Exchange Commission (US SEC), is a KPMG partner, member of the International Auditing and Assurance Standards Board (IAASB), and a member of CPA Australia’s External Reporting Centre of Excellence.

Jui has seen, first-hand, the impact of SOX in the US, and reflects that “the upfront first-year cost of implementing Section 404 of the Sarbanes-Oxley Act has been reported as significantly more than originally projected by the US SEC, but after more than 15 years since the implementation of 404, stakeholders have expressed the benefits have outweighed the initial investment.”

Jui explains that in the US, the most commonly identified benefits include:

- Improved quality of the internal control structure.

- Greater confidence from audit committees about companies’ internal control over financial reporting.

- Higher-quality financial reporting.

- Stronger capability within companies to prevent and detect fraud.

More importantly, Jui says, “investors have shown more confidence in the audited financial statements of 404-compliant companies.”

There is much to be learnt from the US experience, including avoiding the same teething problems and minimising disruption and costs of implementation.