Loading component...

At a glance

- The audit profession is facing pressure to change, following a series of business failures in the UK.

- While audit is faring better in Australia, it is under scrutiny from a new inquiry into its regulation.

- Regulators and stakeholders are likely to demand greater division between audit and non-audit functions.

Independent auditing has long been one of the foundation stones of business, but the profession globally is facing unprecedented challenges – as well as emerging opportunities. No one can say with certainty where the path is leading, but there is a sense that auditing as a profession, and a process, is under pressure.

Much of the current concern has been driven by events in the UK after a series of business failures, notably BHS and Carillion, along with a string of other large corporates, where financial statements were all signed off by one or other of the Big Four audit firms PwC, KPMG, EY and Deloitte. Regulators are now pushing the firms to clearly separate the audit and non-audit services they provide to clients, even to the extent of splitting off into a separate firm.

Speaking recently to a UK parliamentary committee, the heads of PwC, KPMG and EY said they would cease providing non-audit work for large audit clients within a year.

PwC UK has been the first to make serious moves in this area, announcing in June that it would have one business to focus on external audits and another to deal with internal audits and issues such as cybersecurity and technology risk. It also plans to recruit more than 500 auditors, introduce new training and technology, and increase the number of specialists in its audit quality control section.

This will cost about £30 million a year, which is a good indication of the seriousness of the issues.

“Globally, the UK is leading efforts to improve audit quality and avoid conflicts of interest,” says Professor Ian Gow, director of the Melbourne Centre for Corporate Governance and Regulation at the University of Melbourne, and co-author of the book The Big Four: The Curious Past and Perilous Future of the Global Accounting Monopoly, which won the Australian 2018 Ashurst Business Literature Prize. “Yet in South Africa, India and Ukraine, there have also been cases of Big Four firms being excluded from audit work due to sloppy practices,” Gow says.

This raises the question of how auditing is faring in Australia, especially since the Big Four handle audits for more than 90 per cent of the companies listed on the Australian Stock Exchange. It appears that, generally, the situation does not directly compare with the UK.

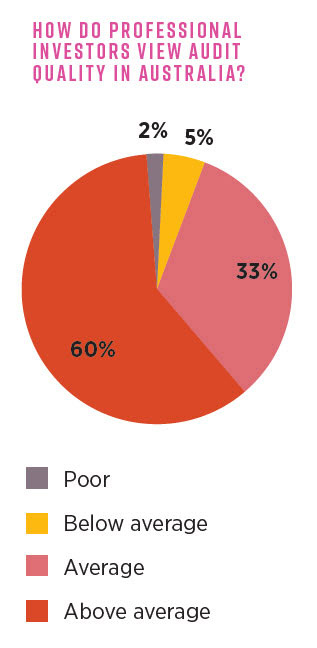

A survey recently released by the Financial Reporting Council (FRC) and the Auditing and Assurance Standards Board (AUASB), Audit Quality in Australia: The Perspectives of Professional Investors, found that 93 per cent of respondents considered audit quality “average” or “above average”.

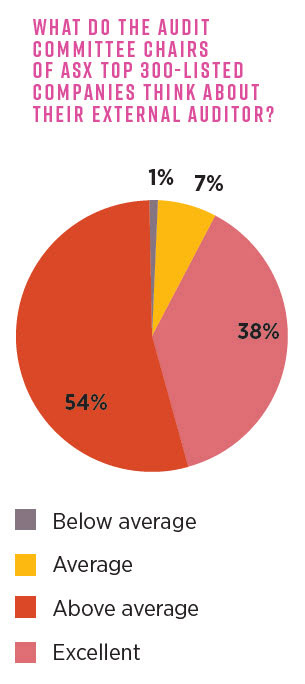

Related to this, another FRC and AUASB survey, Audit Quality in Australia: The Perspectives of Audit Committee Chairs, revealed a high degree of satisfaction with the quality of their external auditor, with 99 per cent of respondents rating the auditor as “average” or better, including 38 per cent rating auditors as “excellent”.

“We were very pleased to see these results, but we can never be complacent,” says Matt Graham, managing partner, PwC Assurance. “For some time, we have felt that the audit quality debate in Australia could be broader, more balanced and aided by increased transparency. This is why we released the country’s first-ever balanced scorecard on audit quality recently. That scorecard showed audit inspection results along with other key measures of audit quality such as internal inspection findings, restatement rates and adjustments to financial statements. We plan to release data like this on an annual basis.”

Corporate regulator the Australian Securities and Investments Commission (ASIC) supports greater transparency and is considering whether to publish individual firm inspection results in its next public report. ASIC is also continuing work on possible additional audit quality measures to complement the inspection findings.

Doug Niven, ASIC’s senior executive leader, financial reporting and audit, says ASIC’s audit inspection report for the 18 months to 30 June 2018 found that in 24 per cent of the key audit areas reviewed, auditors did not obtain reasonable assurance that the financial report was free of material misstatement. This is slightly better than the figure of 25 per cent for the 18-month period ended 31 December 2016.

“Sustainable improvement requires a focus on culture and talent in firms,” says Niven. “Our inspection findings suggest that further work and, in some cases, new or revised strategies are needed.”

CPA Library resource:

However, he is wary of splitting large accounting firms into audit-only firms, believing it could adversely affect audit quality.

Graham says PwC Australia has no plans to hive off its audit business (and none of the other big audit firms have signalled intentions to do so). He sees the business and regulatory environments in the UK and Australia as very different, and says the discussion in Australia should be more broadly aimed at audit quality, independence, conflicts of interest, and the needs of businesses and their shareholders.

Gow is pleased to see moves such as PwC’s scorecard, although he wonders where it will lead. He says all the Big Four have recently started to reveal new information. “Clearly the incentives to reveal more are stronger if your numbers look better,” he says. “I suspect that this wave of disclosure will prompt some tweaks to the inspection process to make the numbers more meaningful. An issue with the reported numbers is that audits are selected for inspection because they are perceived to be ‘risky’ audits, which makes it difficult to draw general conclusions. But overall it seems to be a healthy conversation to have.”

Focus shift

Discussions on ways to improve audit quality are important, but there is an even more crucial question: in the current environment, what is auditing actually for? In an era when emerging technologies allow for real-time tracking of all of a company’s transactions, does the idea of checking and re-checking historical financial data still make sense?

Professional investors and audit committee chairs may be reasonably satisfied with the work of auditors, but there are other stakeholders. There is certainly a bloc of investors that is concerned with a company’s non-financial performance along with the traditional metrics.

While technology has the potential to take over many mechanical, repetitive tasks associated with auditing and operate in real time, big data provides new non-financial information sources that can support or challenge financial information and enable the profession to move towards better predictive and more powerful business analytics.

Graham says: “The industry has to evolve the audit in line with market demands, as well as engaging more effectively with stakeholders along the way. For example, should an audit include new levels of coverage such as fraud, going concern and cybersecurity? Could it provide assurance over non-financial measures such as culture, sustainability and the control environment? Should it look forward as well as back and provide comfort over forecast information?”

In this context it might be noted that the Australian Accounting Standards Board and the AUASB recently released a practice statement, Climate-related and Other Emerging Risks Disclosures: Assessing Financial Statement Materiality.

The practice statement is not mandatory for auditors, but it points auditing towards an integration of financial and non-financial data.

However, auditing financial statements is largely about providing assurance that the statements were prepared in accordance with accounting standards. When auditing looks at issues such as the environment, controls, fraud and cybersecurity, there are no widely accepted reporting frameworks or, where they exist, the detailed criteria against which to check performance are still evolving. More than an understanding of accounting standards is needed as a basis of relevant expertise.

“The Big Four firms are trying to claim a future stake on auditing things such as sustainability, environmental risks and even privacy,” says Gow, “but skills-wise it is a real stretch. Auditors still graduate with accounting degrees that focus on standards and the like. The auditor of the future is likely to be someone who is comfortable with advanced data analytics.”

Niven counsels caution about moving too quickly into the non-financial field. “Investors and other users of annual reports may benefit from independent assurance over non-financial information in an operating and financial review, integrated reporting, sustainability reporting and climate-change reporting,” he says. “However, at present there are no detailed reporting frameworks to audit against and many of those promoting innovation by companies in non-financial reporting suggest that independent assurance is premature.”

Competition pressure

Another issue relates to competitive pressures. Gow says his current research shows that audit fees generally increase slightly over time, and often decline markedly when a new auditor is appointed. This suggests that some audit appointments are based on price.

“This could be a concern,” he says. “I suspect the Big Four would rather compete on quality. The problem is that audit quality is very difficult to measure, so it is hard to prove that you are adding sufficient value to justify the costs.”

There is also the possibility that competition may come from smaller, more nimble firms that can offer assurance services in non-financial areas for which they have specialist expertise.

What might the future of auditing look like in Australia?

In short, while financial review is likely to remain the essential core of auditing practice, it might cease to be the reliable source of revenue that it has long been for the large firms. Regulators and stakeholders are likely to demand greater division between audit and non-audit functions, although pressure for complete separation is unlikely.

Auditing firms will have to go further into non-financial issues, requiring a significant change in the firm’s collective expertise. At the same time, they will face increasing competition from new entrants, bringing specialist expertise in either emerging subject matters, such as culture or climate risk, or technological solutions for conducting the audit.

“One is always hesitant when trying to predict the future, as so many past predictions turned out to be wrong,” Gow says, “but one thing is clear: it’s going to be a very different profession from what it is now.”

Australian audit quality inquiry

Audit is also under scrutiny in Australia.

In August, the Parliamentary Joint Committee on Corporations and Financial Services announced an inquiry into the regulation of auditing in Australia. The terms cover the relationship between auditing and consulting services, and potential conflicts of interest, audit quality and the level and effectiveness of competition in audit and related consulting services. The report is scheduled for release on 1 March 2020, and the deadline for submissions is 28 October 2019. More details are available on the Parliament of Australia website.