Loading component...

At a glance

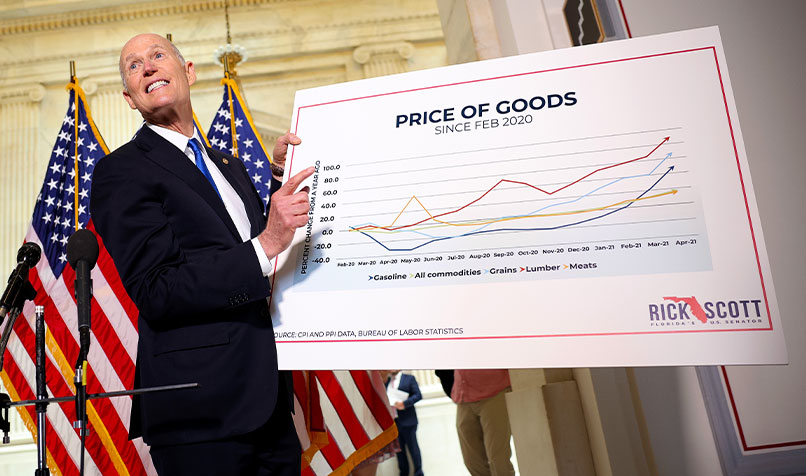

The transition to net‑zero emissions is no longer negotiable, but that does not mean it will be easy – or cheap. Decarbonising the global economy requires trillions of dollars in annual spending on physical assets alone, and the inflationary effect of the switch to sustainable energy sources is hotly contested.

Is so‑called “greenflation” a legitimate cause for concern, or is “fossilflation” the greater source of upward pressure?

Net‑zero pledges are now ubiquitous among corporate strategies, investor portfolios and the broader economic development plans of governments. A report from the Energy & Climate Intelligence Unit and Oxford Net Zero shows that net‑zero targets are in place across two‑thirds of the global economy. This represents a significant advance in climate ambition since the Paris climate summit of 2015.

The faster the transition is, the more expensive it may be in the short term. Demand is expected to outstrip the supply of metals and minerals required for green technologies.

When the price of lithium – used in batteries for electric cars – reached a record US$78,000 (A$117,250) a tonne in April 2022, Tesla CEO Elon Musk announced that the company might begin mining and refining the mineral directly at scale, unless costs improved.

Tony Wood, energy program director at the Grattan Institute, says limited resources required for green technologies could add to the cost of the transition “fairly materially”.

“When the price of a critical input to electrification goes up by several thousand per cent, you can see why there’s a risk that costs of renewable energy start to go up pretty steeply.

“I’ve seen some numbers that are eye‑wateringly challenging in terms of how much the price of things like copper and aluminium are going up. We’ve also recently seen BHP expand its nickel business due to demand,” Wood says.

The green future of sustainable finance

Greenflation or fossilflation?

According to Dr William Paul Bell, research fellow at the Centre for Applied Energy Economics and Policy Research at Griffith University, any inflationary impact from the net‑zero transition is overwhelmed by cost spikes from fossil fuels – referred to as fossilflation.

“If we hadn’t had a war in Ukraine, I’m sure we wouldn’t have had this massive increase in energy prices. The gas and coal going into energy generation make up about 35 per cent of the electricity bill for consumers, and the cost of the inputs of gas have increased almost fivefold since the beginning of 2022,” Bell says.

Bell also describes fossilflation as a “downer on demand”.

“It’s just a cost for people, while if you’re investing in new stock and new renewable energy, it’s going be a boost to the economy.

“In the long term, the marginal cost of renewable energy is very low, because wind and sunshine are basically free once you put the capital costs in. It’s going to be a lot cheaper than our existing system,” Bell explains.

Fossil fuel generation fleets in countries such as Australia are also nearing retirement.

Dr Steve Hatfield‑Dodds, associate principal at strategy consulting firm EY Port Jackson Partners, says it does not make sense to replace these fleets with more coal‑powered stations.

“Australia’s investment in electricity generation was quite ‘lumpy’. It all happened basically in the same decade across all the east coast states,” Hatfield‑Dodds says.

As result of this, most of Australia’s coal‑fired stations will be due for retirement at around the same time.

“As we use fossil fuel in assets we already have, it’s hard to substitute away. Most businesses can’t say, ‘Today I’m going to run on coal, tomorrow I’m going run on oil, and the day after that I’m going to use solar’.

“This means your near‑term decisions are pretty much locked in. Even if you wanted to hurry, with supply chain constraints, it would take 18 months to flip your vehicle fleet from diesel to batteries,” Hatfield‑Dodds explains.

Hatfield‑Dodds also says that demand for fossil fuels is “inelastic”, especially in the short term, so tiny changes in volume can lead to very high prices.

“That’s all we’re seeing at the moment. Fossil fuels are driving up prices. The idea of greenflation is rubbish,” Hatfield‑Dodds argues.

CPA Australia’s Net Zero Emissions Pathway

Green lending

Upward pressure on prices may be an inevitable part of the net‑zero transition, but downward pressures are also possible, due to cheaper costs of capital.

Since the Glasgow COP26 Conference in 2021, the finance sector has become more central to climate change discussions.

The Global Finance Alliance for Net Zero has grown by more than 20 per cent to about 550 members, who collectively represent more than US$80 trillion (A$120 trillion) in financial assets under management, US$70 trillion (A$105 trillion) in banking financial assets, and US$700 billion (A$1.05 trillion) in gross written premiums.

More than 120 banks from 41 countries have also joined the Net‑Zero Banking Alliance, which covers 40 per cent of global banking assets.

The World Economic Forum’s report Financing the Transition to a Net‑Zero Future, prepared in collaboration with Oliver Wyman, notes that US$50 trillion (A$75 trillion) in incremental investments will be required by 2050 to shift the global economy to net‑zero emissions and avert a climate catastrophe.

Ross Eaton, partner in financial services and climate and sustainability practices at Oliver Wyman, says there is greater expectation for central banks, commercial banks and institutional investors to accelerate investment into low‑carbon solutions and opportunities.

"I’ve seen some numbers that are eye‑wateringly challenging in terms of how much the price of things like copper and aluminium are going up."

“The immense magnitude of change required to reach net zero is going to require a huge amount of capital.

“We’re working with financial institutions around the world on how to manage their portfolios to meet the new net‑zero targets, and part of this is going to involve a more expensive cost of capital for brown assets and a lower cost of capital for green assets. Simply put, we’re already seeing this play out,” Eaton says.

“When you look at the disclosures from the banks, they’re proudly announcing the volumes they’ve done in green financing, and many of them have targets to wind down fossil fuel lending.

They are certainly getting a lot of investor pressure to do that. The intention is that the financial sector can play a huge role in tilting the cost of capital and steering the world in the right direction,” Eaton explains.

Sally Torgoman, partner in commercial advisory and transactions at KPMG, says the major banks are generally “excited” about supporting renewable asset classes, but there is still an expectation of returns.

“At the end of the day, projects have to meet return hurdles and investor expectations, otherwise investors won’t be very keen to go down that pathway,” Torgoman says.

Cost management

Torgoman says diversification is the key to a smooth energy transition.

“When you want to displace one type of technology with a clean technology, you can’t just back one horse.

“In our market, we are going to need diversity, because we will need different generators that create electrons at different times of the day. We’ll also need diversity in ‘firming options’, like hydrogen and different types of batteries,” Torgoman says.

"In our market, we are going to need diversity, because we will need different generators that create electrons at different times of the day. We’ll also need diversity in ‘firming options’, like hydrogen and different types of batteries."

While investments into renewable energy vary across the globe, some countries are also seeking to manage the costs of the net‑zero transition.

In the US, for instance, the Inflation Reduction Act of 2022 marks the largest federal clean energy investment in US history. The legislation includes US$369 billion (A$556 billion) investment

in clean energy and climate change mitigation initiatives, including tax credits for households to offset energy costs and for reducing carbon emissions, plus funding for clean energy production.

Singapore has implemented the Carbon Pricing (Amendment) Act 2022, which allows the nation to progressively increase its carbon tax from the current rate of S$5 (A$5.50) per tonne of greenhouse gas emissions to S$25 (A$40) per tonne in 2024 and 2025, and then to S$50‑S$80 (A$55‑A$80) per tonne by 2030. This will make Singapore’s carbon tax rates equivalent to those of Ireland, Finland and the EU Emissions Trading System, based on current carbon prices.

The key to future-proofing manufacturing

Innovation to the rescue

The price of renewable energy is declining, and global growth in green energy technologies is staggering, Wood says.

“If you look at the cost curve and the cost reduction of wind and solar energy, no one could have predicted how dramatic it would be.

“It has come down 80‑90 per cent in 10 to 15 years. The consequence has been a global growth in renewable energy technologies,” Wood says.

A sticking point, at least for the short term, is the cost of minerals required for large‑scale battery storage.

“We need to be able to make batteries more cheaply than with lithium,” adds Bell. “It’s just a matter of time before engineers crack that one and give us cheap batteries, which can be made out of extremely abundant cheap material.”

This is already happening in Spain, where Barcelona‑based battery company Bioo is generating electricity from natural soil. Its biological batteries power assets such as agricultural sensors.

“I don’t think we should in any way give up and say, well the price of copper or nickel is going to completely constrain or blow out the cost of the net‑zero transition,” Wood says. “I certainly wouldn’t give up on people’s capacity to innovate.”

The cost of the net‑zero transition may be higher than we would like, but this cannot stop progress, Wood says.

“If you accept the science of climate change, we just can’t stop – we have to keep going. The question is going to be how we make sure that we do this at the lowest cost.”

The time of companies thinking they could drop out of the net‑zero transition has passed, Wood says.

“The Task Force on Climate‑Related Financial Disclosures, prudential authorities around the world, investment banks and infrastructure funds – all those sorts of organisations are moving in the same direction. Governments are pretty well lined up as well.

“Momentum is now virtually unstoppable. But that doesn’t mean there won’t be a few bumps along the way,” Wood says.