Loading component...

At a glance

- The gaming market is the largest sector in the entertainment industry, valued at more than US$145 billion.

- Esports is classed as the competitive side of gaming, and projected revenues in the sector range from US$1 billion (A$1.3 billion) to US$3 billion (A$4.1 billion).

- Several Esports organisations are listed on leading stock exchanges, indicating that spending and investment in the sector are on the rise.

Darren Kwan was sports mad as a kid. He played soccer and rugby, and competed in athletics throughout school and university. When he started playing video games at the age of 15, he approached it with the same competitive mindset.

“I have one of those competitive personality types. When I play a game, I want to become good at it,” he says. “As a teenager, I didn’t see the difference between playing soccer with my friends or playing video games – I wanted to be better than them.”

Kwan competed in esports tournaments right up until he graduated with a degree in economics. He then quit esports to focus on his career, which began at a boutique finance firm.

“Ten years ago, a career in esports wasn’t possible. It wasn’t the big industry that it is today,” he recalls.

By its sheer economic size, esports is an industry that is increasingly hard to ignore. Gaming is worth more than US$145 billion (A$199 billion), making it by far the largest entertainment industry.

Kwan continued playing esports as a hobby, and in 2013 he founded the Australian Esports Association. Three years later, he left the world of finance to devote himself full-time to esports. He is now president of the association, as well as executive producer of the Australian Esports League. In 2016, he oversaw the first televised broadcast of esports in Australia, the same year that the first esports teams went overseas to compete in the nation’s most popular game, Counter-Strike.

Money talks

Esports is comprised of many different categories, with different games within those categories. “I liken it to athletics, where there are a number of different competitions within it,” explains Kwan.

There are the esports versions of traditional sports, such as FIFA’s videogame series and MotoGP eSports Championship. However, the most popular esports titles tend to be games that are unique to esports, like League of Legends, which is a multiplayer online battle arena (MOBA) that focuses on strategy skills. League of Legends is regarded as having reshaped the landscape of esports by generating tens of millions of dollars in prize pools.

Esports is the competitive side of gaming, and estimates of projected revenues range from US$1 billion to US$3 billion, says James Walton, sports business group leader at Deloitte Southeast Asia.

"There's a great divergence in terms of what people feel the potential revenue is of eSports at this point in time. It's difficult to quantify because of how fragmented the industry is in terms of different leagues and organisations in different countries."

“There’s a great divergence in terms of what people feel the potential revenue is of esports at this point in time,” he says. “It’s difficult to quantify because of how fragmented the industry is in terms of different leagues and organisations in different countries. And so much of this is ‘finger in the wind’.

“With Major League Baseball, it’s easy to track the revenues – you look at things like ticket revenues, TV rights and merchandise sales. With people watching esports at home all around the world, it is challenging to put a figure on it.”

Nonetheless, esports is growing at a faster rate than almost any other sport, and it has benefited enormously from COVID-19 lockdowns as the only sport that could continue almost without interruption. “An esports world champion could sit in their house and play another champion across the globe, and spectators could watch without any issues,” says Walton.

“And, from a spectator point of view, watching it from home may be better than watching it in a stadium – in some ways it is similar to watching a sport like poker, in that the competition area is very small, and as a spectator you need to see each player’s perspective and not the view from your seat.”

Investment to pick up pace

Several esports organisations are listed on the NASDAQ and New York Stock Exchange, which Walton interprets as “a sign that the spending and investment is going to increase”. High profile esports investors include Shaquille O’Neal with a stake in NRG Esports, Michael Jordan with Team Liquid and David Beckham with Guild Esports.

“For a lot of these guys, it fits into their branding portfolio, because it is still sports. It’s also a way of staying relevant, because if you’re Shaquille O’Neal, you’ll be reaching the point in the next couple of years where some of the young people won’t have seen you play.”

While there is much hype around esports, perspective is important. Esports as a whole is still a long way from overtaking even a single traditional sport like baseball or soccer.

“Even if the highest estimate of, say US$3 billion in 2022, is correct, the NBA made roughly US$8 billion in 2020. One of the big European soccer leagues is around US$15 billion,” says Walton.

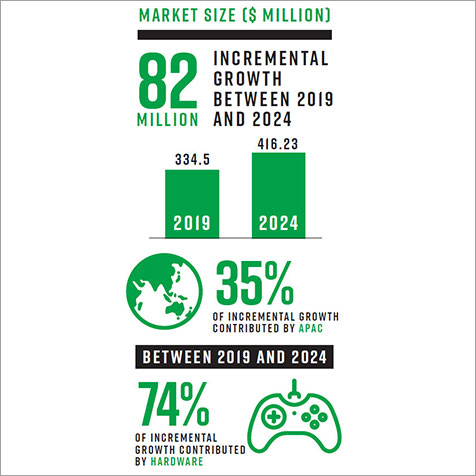

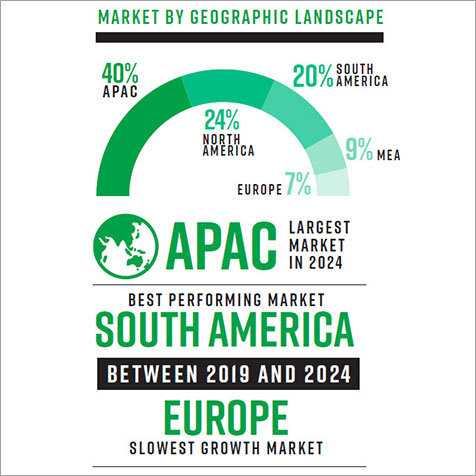

In Australia, esports revenue growth is undoubtedly healthy, albeit slower than in other markets. It was A$6 million in 2020 and is projected to grow to A$16 million by 2025, representing a 21.2 per cent compound annual growth rate, according to Samantha Johnson, partner at PwC.

“In some respects, Australia is lagging,” says Johnson. “A couple of the biggest players have pulled out of Australia’s local market, citing challenges around audience size. And probably to an even greater degree, our internet speeds are behind some of those markets. A millisecond of latency can be the difference between winning or dying in a game. This needs to be addressed before we can start to see significant wholesale investment in esports.”

Kwan tracks private investments into esports in Australia and estimates that A$20 million has flown in during the previous 12 months. Australia has about 1000 professional esports players, some of whom are making millions, while others have a second job to supplement their income.

“The career pathways are becoming clearer,” Kwan says. “A starting point was supporting schools in being fitted out to participate in esports. Whereas before a lot of high school students were playing on their own at home, now they have institutional support. Australia now has over 14 universities participating in esports, and 27 of them have club facilities on campus.”

"It's like buying the New York Knicks"

Ferdinand Gutierrez is on a mission to build champion esports teams and gaming personalities. He is the founder and CEO of Ampverse, an esports holding company based in Singapore, which owns and operates esports teams in Thailand, Vietnam and India.

“A lot of esports companies out there weren’t taking advantage of the commercial opportunities,” he says. “Some of the owners are just kids who started a team and thought, ‘We can just win tournaments and get sponsorships and prize money.’ But, in order to succeed, you need diversified revenue streams to survive as an esports business.”

Ampverse uses talent recognition software that allows it to identify up-and-coming players and influencers, and sign them early in their gaming career. The software tracks not only gaming skills, but also popularity on social media platforms.

"esports is still in its infancy. Right now, buying eSports teams is like buying the New York Knicks in the early days of the NBA... We buy teams at a good price, then we surround them with diversified revenue initiatives to become profitable."

“Esports is still in its infancy. Right now, buying esports teams is like buying the New York Knicks in the early days of the NBA. Today, the Knicks are a billion-dollar franchise. We buy teams at a good price, then we surround them with diversified revenue initiatives to become profitable,” Gutierrez says.

One way of doing that is through team sponsorships – and this includes team members who don’t play themselves. These are known as “cultural ambassadors”.

“Sometimes, the players themselves are not the most exciting people in the world, so we supplement them with gaming talent who connect our fans to different ‘verticals’ while being exclusive to our esports teams. Their main job is to connect the team to music, movies and other passion points that are part of a gamer’s lifestyle.”

Gutierrez’s biggest dream is for one of his teams to produce a global esports star.

“That would really solidify our position as a company that understands esports,” he says. “We want to break through just being popular with the esports crowd. We want to become an organisation with mass appeal.”

Keep an eye out for esports on a bigger stage – it’s coming to the Olympics sooner than you think.

Will Singapore become the eSports capital of the world?

The Singapore Games Association (SGGA) is the primary trade association advocating for Singapore’s games and esports industry. Founded in 2020, its aim is to “place Singapore’s gaming brand on the world map” and cultivate the growth of Singapore-based games and esports companies.

“Singapore is trying to position itself as the digital leader – and that goes for digital banking, fintech and esports,” says Walton. “It has the technology infrastructure and very good bandwidth, plus a wealthy society who can afford to buy the latest hardware and software.”

Elicia Lee, SGGA’s vice-chair, says that esports is still a relatively nascent industry in Singapore, and in Southeast Asia, as compared with the Americas and Europe.

“Still, Singapore has a lot going for it,” says Lee. “Our track record of handling the pandemic, for example, has increased confidence in international esports players to bring top-tier tournaments to Singapore, such as the DOTA 2 Singapore Major and the M2 World Championship.”

Lee is seeing increasing interest from the Singapore government to support the gaming and esports industry.

“Enterprise Singapore has been very proactive in engaging and providing support for Singapore-based start-ups, and the Ministry of Culture, Community and Youth has supported events.”

However, Singapore faces stiff competition. The US already has several world-class esports centres, and China is building two in Shanghai and Hangzhou, which would be the largest in Asia, Walton says.

“The one being built in in Hangzhou is actually called the ‘Hangzhou eSports Town’,” he says. “It has a theme park, a hospital and a research and development centre.”