Loading component...

At a glance

- Professor Veena Sahajwalla is the inventor of polymer injection technology, known as green steel, an eco-friendly process for using recycled tyres in steel production.

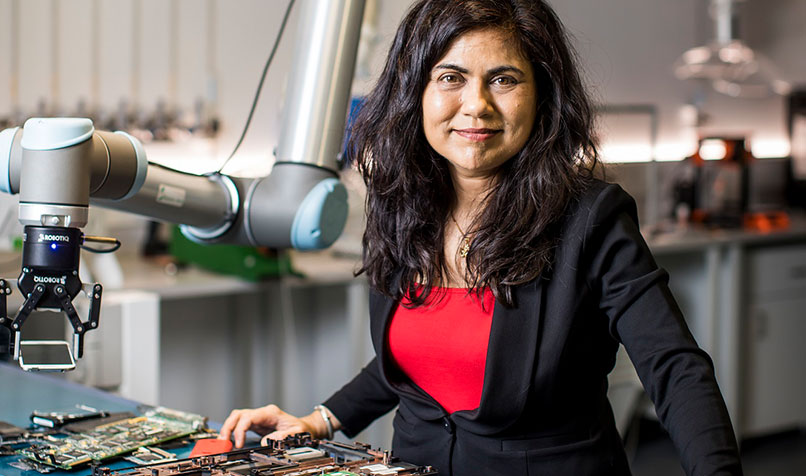

- Sahajwalla launched the first e-waste microfactory, which processes metal alloys from old laptops, circuit boards and smartphones.

- She views waste as an opportunity, not a problem, and hopes to roll out the microfactory model across the world.

When China announced a ban on the importation of 24 types of solid waste in January 2018, the inherent inefficiency of Australia’s A$15 billion waste industry was suddenly exposed. An annual average of 619,000 tonnes of Australian recyclable materials were left without a home. The nation was facing a waste crisis, but Professor Veena Sahajwalla had a strategy for tipping the materials straight back into the economy.

As founding director of the Centre for Sustainable Materials Research and Technology (SMaRT) at the University of New South Wales (UNSW), Sahajwalla is revolutionising recycling science in collaboration with industry. Last year, she was appointed director of the NSW Circular Economy Innovation Network, which brings together stakeholders from across government, industry and research organisations to develop new processes and supply chains for reducing waste and improving sustainability.

In 2003, Sahajwalla invented polymer injection technology (PIT), known as green steel.

An environmentally friendly and cost-effective process for using recycled rubber tyres, the technology has been licensed to steel makers globally, and Sahajwalla and her team are working with Newcastle-based steelmaker MolyCop, which plans to implement the technology across its global operations.

In 2018, Sahajwalla launched the world’s first e-waste microfactory, where valuable metal alloys are extracted from discarded smartphones, laptops and circuit boards. Now she’s converting waste materials, such as the glass, plastic and textiles Australia previously exported or sent to landfill, into industrial-grade ceramics inside a second microfactory. She also plans to roll out her microfactory model across the country and, ultimately, the world.

Capturing value in waste

Sahajwalla grew up in Mumbai, where she says waste was viewed as an opportunity rather than a problem. Rubbish heaps were trawled for plastic, cardboard and other materials of value to sell on to scrap dealers.

“The sense of repurposing and reusing, and sharing was driven by economic necessity, of course, but people were more than happy to have hand-me-downs, whether it was clothes or furniture items,” Sahajwalla says. “We would rarely throw away things that were in decent working order.”

While Sahajwalla’s mother is a medical doctor, her father was a civil engineer, and she loved visiting his construction sites to see how things were built. “A Cadbury factory was my favourite,” she recalls. “When I think about it now, it was probably just an office building rather than an actual factory, but when you’re a kid and you see the symbol of Cadbury, making and how they got the liquid chocolate to become that solid slab and all the challenges there must have been to get it right.”

That early interest in materials science led Sahajwalla to study engineering at the Indian Institute of Technology, where she was the only woman in her class. She went on to earn her master’s degree at the University of British Columbia and, while completing her PhD at the University of Michigan, she was offered a job at Australia’s national science and research agency, CSIRO.

Wheels in motion

Sahajwalla’s stint at the CSIRO led to an academic position at UNSW, and it was in one of the university’s laboratories that she pioneered her green steel technology.

In Australia, 50 million vehicle tyres reach the end of their life each year, and only 16 per cent are recycled. Sahajwalla’s technology involves melting down carbon-rich rubber tyres to replace some of the non-renewable coke in the production of steel.

Rubber is cheaper than coke. It also creates less waste, which represents a cost saving to industry.

When rubber is transformed into smaller molecules in a furnace, millions of rubber tyres have been diverted from landfill thanks to Sahajwalla’s innovation.

“When we talk about recycling, it’s generally about converting like for like – converting a plastic bottle into another plastic bottle, for instance – but this is quite limited,” Sahajwalla says.

“Old tyres are no longer roadworthy, so they can’t be reused as tyres. What if you can see that old tyre as a collection of molecules that can be transformed and used in other manufacturing solutions?”

Power of collaboration

In 2005, Sahajwalla won the prestigious Eureka Prize for her green steel invention and, while she describes it as a “wonderful outcome”, the scientific recognition was not enough.

“I wanted to use the research outcomes to create sustainable industry practices,” she says.

“I needed to be able to show the steel industry that the benefits were not just environmental, but also economic.”

Fast-forward over a decade, and she has visited countless manufacturing centres across the country to promote the environmental and economic benefits of green manufacturing.

She says engaging with the business community has been vital to getting her innovations to market.

“We need scientific collaborators,” she says. “We also need [industry] partners who are open to trying new products and seeing the benefits in the longer term.”

"Waste is not a problem to be managed; it is an opportunity to be explored."

Michael Sharpe, national director – industry at the Advanced Manufacturing Growth Centre, says Sahajwalla “understands the path to commercialisation and what it takes to be successful”.

“Veena and I have walked the factory floors in places like Dubbo and Armidale to talk about robotics and automation, and we’ve spoken with manufacturers in Perth and Adelaide about the benefits of recycling and the circular economy,” he says.

“At every point, Veena is open about the possibilities that exist for manufacturers, and this has led to companies coming in from across Australia to visit her at UNSW’s SMaRT Centre to investigate ways of developing new technologies. Veena knows what it takes to have a go, but, most importantly, how to have a beneficial impact.”

The microfactory of the future

Many of these new manufacturing technologies are being developed via Sahajwalla’s unique microfactory model.

Microfactories feature a series of small machines and devices that use patented technology to perform one or more functions in the reforming of waste products into new and usable resources.

They can be installed in an area as small as 50-100 square metres, and can be set up wherever waste is stockpiled, such as a building site or alongside regional waste disposal sites, to process waste at the source.

Sahajwalla says the microfactory model may disrupt the current highly centralised, vertically integrated industrial model.

“My model is one that is laterally integrated to allow different operators in the supply chain to connect,” she says.

“If you can localise your solution, you’ve actually enabled everybody across the country to benefit by enhancing our manufacturing capabilities.”

The first microfactory was launched at UNSW with funding Sahajwalla received from the Australia Research Council (ARC), to convert electronic waste input into new products. Electronic devices are broken down and scanned by a robotic module to identify useful parts, which are then transformed into valuable materials.

Computer circuit boards, for example, can be turned into valuable metal alloys such as copper, while plastics can be converted into filaments for 3D printing, which Sahajwalla describes as a “cost-effective” alternative.

E-waste microfactory industry partners include MolyCop, e-waste recycler TES, and spectacle manufacturer Dresden, which makes its frames from recycled plastics.

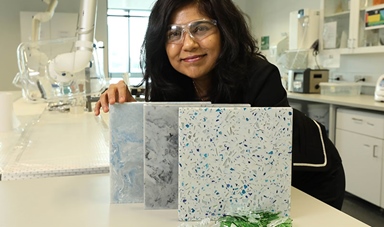

A second microfactory was launched at UNSW last year, to transform waste materials such as glass and textiles into tiles, ceramics and panels that can be used for building products and furniture.

Industry partner Mirvac has used Sahajwalla’s ceramic tiles in its new apartment complex in Sydney’s Marrickville.

Diana Sarcasmo, general manager design, marketing and sales at Mirvac, says the partnership is part of the company’s sustainability strategy to achieve zero waste to landfill by 2030. The Marrickville project is located on the site of an old hospital, with 90 per cent of construction waste recycled.

“Veena is incredibly engaging and passionate,” Sarcasmo says. “She’s a true collaborator.”

Mirvac is looking to set up its own microfactory on one of its building sites. “The whole idea of having a local plant is that we wouldn’t be using transport, so we could recycle what we’ve got on site and then keep it onsite, so that we can tap into the circular economy,” Sarcasmo says.

This is exactly what Sahajwalla had hoped for her microfactory model. The global rollout has already started – Sahajwalla is talking with engineers in India to set up microfactories across the country.

“The value-added part of creating highly valuable products [from waste] that can be sold into the economy has not quite happened in places like India,” she says. “

There’s been a lot of front-end work with waste being collected, but we want the economy to reward everyone in that supply chain.”

Sahajwalla sees innovations such as microfactories and green steel technology as new export opportunities for Australia.

“With green steel, we’re not putting steel on a ship and sending it away,” she says.

“We’re exporting our knowledge and our intellectual property. Waste is not a problem to be managed; it is an opportunity to be explored.”

Q&A with the inventor

You are an inventor. What does a “eureka” moment feel like?

It’s absolutely exhilarating. Even if it doesn’t present the complete solution to a problem, discovering what you think may work leads to the next step. It’s a great feeling. You get goosebumps.

Did you develop any new routines during the COVID-19 lockdown?

The lack of clear routine has been good for me. It means that I have had more fabulous thinking time, because I haven’t been caught in traffic, driving to and from work.

What is the greatest lesson you’ve learnt in your career?

The more people think that something is impossible, the more likely that a solution can be found if you put your mind to it.

What are you currently reading?

I’m reading The Cattle King by Ion Idriess, which is about [Australian pastoralist] Sir Sidney Kidman and how he built his cattle empire. It captures the Australian spirit.

Do you have any advice for budding innovators?

When you challenge the norm, you will have the spirit of innovation in you. Don’t ever let it die! People might think you’re crazy because your ideas are different, but don’t let it bother you.

Reforming and recycling

The Australian Council of Recycling and the Waste Management and Resource Recovery Association of Australia (WMRR) estimate a A$150 million investment by federal and state governments is required to reboot the local recycling industry and foster the creation of a circular economy.

Sahajwalla says green manufacturing is a vital part of the circular economy. In addition to her role at UNSW and NSW Circular Economy Innovation Network, she also heads the ARC Industrial Transformation Research Hub for green manufacturing, which works in collaboration with industry to ensure new science is translated into real-world environmental and economic benefits.

“It’s not entirely funded by government,” Sahajwalla says. “Industry contribution is vital to the model.”

Green manufacturing aims to transform traditional business and manufacturing practices – and the mindset of stakeholders – to reduce the industrial impact on climate change and other environmental concerns.

Sahajwalla thinks about green manufacturing as “reforming” in addition to recycling.

“You’re not necessarily converting something into the same product, but rather reforming it into something else,” she says. “There’s a huge amount of embedded value in things like everyday electronic products, so why shouldn’t we tap into it and create that value right here in Australia, rather than sending it away for someone else to tap into? I think manufacturers are really excited about it – they are seeing lots of new opportunities coming down the pipeline.”