Loading component...

At a glance

Despite being on the other side of the world, standing in an apartment in Chelsea, Manhattan, Australian Dare Jennings does not look out of place.

Sporting a blue button-up shirt, black-rimmed glasses and a Bell & Ross watch, the man before me represents everything his multimillion-dollar business stands for: comfortable clothes for the discerning bloke who may or may not ride a motorcycle and isn’t afraid to embrace the occasional luxury item.

He may look relaxed, but Jennings’ big, calm face and happy demeanour belie what colleagues describe as a marathon-racing mind.

He never switches off; is never not thinking about the machine that is his ever-expanding brand, Deus ex Machina.

The New York office and makeshift showroom is where Jennings recently posted his global sales manager, Omar Varts, to oversee expansion to the Big Apple and operations in the US and Europe.

After all, from here it’s only a seven-hour flight to Paris. And Jennings, although it’s hard to believe, can’t be everywhere at once.

Yet, in many ways, he is. Sitting on the coffee table in front of us is part-owner Carby Tuckwell’s 252-page tome on the brand, The Book of Deus, filled with illustrations, photographs and T-shirt designs.

Racks of clothes from the Spring Summer 2014 collection – boardies, coloured sweaters and canvas jackets – hang next door. All that’s needed to make this a Deus store is a cappuccino and a motorbike.

If you’ve never set foot in a Deus store you may find it hard to believe a motorcycle shop, bustling cafe and fashion retailer can coexist under one roof.

Not only does the idea work, Jennings’ mix of custom machines, colourful artworks and surfing attire somehow also manages to keep the whole family occupied.

At 63, Jennings is in no rush to slow down. This latest trip has him flying into South America en route to China and South Korea as the brand he launched eight years ago gains headway around the globe.

But at this particular moment, New York, with its ambulance sirens, roaring buses – and bike riders – is front of mind. It’s a potentially lucrative destination for the next Deus pit stop.

Often hailed as an “accidental success story” or “barefoot billionaire”, Jennings is the university dropout who hurled Mambo into the staid Australian fashion landscape in 1984, creating a market for scruffy shirts emblazoned with irreverent slogans and vibrant illustrations.

The motorcycle outfit came in 2006, five years after he sold Mambo to Gazal Corporation for somewhere between A$20 million and A$30 million.

His reputation meant the new venture was noticed, but Deus was by no means a roaring success – it began as a couple of shirts in a motorcycle shop on a shabby strip of Sydney’s Parramatta Road.

Today, of course, it’s much more than that. Jennings’ ability to pinpoint the zeitgeist is legendary: he creates cultures, in this case a club for bike enthusiasts, a place to buy cool surf T-shirts, a weekend brunch stop, a domicile for a top-quality flat white.

With stores also in Los Angeles, Milan and Bali (and hubs in Paris, Amsterdam and Tokyo on the way), Deus has become a global philosophy adopted by Ryan Reynolds, Orlando Bloom and Billy Joel. And you get the sense that was Jennings’ plan all along.

In 2010 I took a taxi to the Deus store in Sydney’s Camperdown.

“I’m going to Deus,” I told the driver. “Deus Ex Machina – on Parramatta Road.”

“I haven’t heard of that one,” he said, brow furrowed. “You’ll know it,” I said. “Big motorbike shop. Day-us Ex Mack-in-a.” I sounded it out.

We drove while he thought hard about it. Then I tried another tactic. “You might know it as Deuce?” “Oh, Deuce!” he exclaimed. “Gotcha. I love that place.”

The irony in the early days was that a community of people adored Deus, but had no idea how to pronounce its name.

“Yeah, that was really clever, wasn’t it?” Jennings deadpans. “I know advertising people who said ‘you’re mad to do it’, but it’s funny because people talk about it and not only that, argue and discuss how to pronounce it. It stays in their heads. People couldn’t say Versace,” he reminds me.

“And everyone learned how to pronounce it and were awfully pleased with themselves when they did.”

Jennings is used to being told how not to do things, but says: “As soon as people tell you that you can’t do it, that’s when you should do it. If you keep challenging a preconceived idea, you can keep people coming back – and keep them talking about it.”

Much of Jennings’ success stems from trusting his instincts. On a trip to Shinjuku in Japan in the late 1990s, he discovered a motorcycle culture where young guys stripped the panels on their bikes back to the metal and rebuilt very simple, beautiful models, in a nod to the British cafe racer bikes culture of the 1950s and 1960s.

Combine that inspiration with Jennings’ love for the Australian surf lifestyle, and you can see the seeds of Deus sprouting in his mind. “When I was in my 20s, in the 1970s – before the era of Billabong and Quiksilver took surfing off to become this thing they wanted it to be – all my friends rode motorbikes and went surfing ,” he says. “There was no cultural distinction.”

Angus Kingsmill, who bought Mambo from Gazal a few years ago through a consortium known as the Nervous Investor group, says: “There are a few mantras I live by, but I like ‘Make money by doing something you love every day’. Dare created a brand, the pillars of which are ‘surf, music, humour, art, free beer and complimentary tickets’. Just as Dare was the first to fuse the worlds of surf, music, art and humour with Mambo, he now combines his love for motorcycles and a great coffee through Deus. Genius.”

Jennings’ propensity to think big stems largely from his upbringing. His parents met during World War II and he and his sister, author Kate Jennings, were raised on a farm in Griffith, New South Wales, in the 1950s.

“My mother was this vivacious city girl and they ended up on the land and she was bored – she filled our heads with ‘go, get out of here’,” he says. His father’s constant fear of doom likewise instilled in him a sense of caution. “I think that’s why I’ve just been so pushy – you can never be a complacent farmer, that’s for sure.”

The young Jennings took himself to Sydney, where he attended university briefly on a teacher’s scholarship before dropping out. He made regular visits home by hitchhiking down the Hume Highway, riding in trucks.

It was on one such trip that he noticed the driver wearing an imported Mack Trucks T-shirt. It gave Jennings the idea to screen-print his own and sell them to friends.

He founded Phantom Textiles Printers in 1974 and Phantom Records in 1978 – a label that helped launch bands such as the Hoodoo Gurus and The Cockroaches.

Mambo began life as an after-hours project in the record label’s art room. Jennings changed the name to 100% Mambo after a phrase he’d seen on a T-shirt in Tokyo.

The early graphics were created by in-house artists such as Richard Allan, whose notorious Call of the Wild (Farting Dog) became one of Mambo’s most popular designs.

With business partner Andrew Rich, Jennings grew Mambo into a popular and profitable brand that was the antithesis of other surfing brands.

A mix of surf culture, art and music, it was everything Jennings loved mashed up and slapped on the front of T-shirts.

The designs were funny and often irreverent stabs at political or religious fundamentalism.

“His initial perception, because he was a surfer, was that all the mainstream surf brands were really boring. All they had was logos and a crappy corporate style and decorations on their gear,” says artist and musician Chris O’Doherty, more commonly recognised as Reg Mombassa. “He thought that was pathetic, which it was, and he wanted to do something more interesting that had more context.

“In a way, what happened with Mambo, which was sort of accidental, was that it was like an art movement – a commercial art movement. It developed a mind of its own, really.”

Mombassa says he liked Jennings’ approach: he was given free rein to produce what he wanted most of the time and the two men shared a childish sense of humour.

“I remember once he came back after a trip to Europe with all these books on stained glass windows. He was excited about it, so I did a few fake stained glass windows with religious subject matter. But generally … I came up with ideas just by free association. I just did what kind of amused me. And if Dare was amused by it, he would use it.”

Mambo’s rise culminated with the 2000 Sydney Olympic Games, for which the company was approached to create uniforms for athletes and dirigibles for the closing ceremony.

It was a bit mainstream, bordering on conservative, says Mombassa, but Jennings talked him into it and in the end he was glad they did it.

The brand did suffer a bit of backlash, however, from young people who saw Mambo as too popular after that and “came to the conclusion that their big, fat fathers and uncles were wearing the shirts, too”.

That same year, Jennings sold Mambo. It was time for a new challenge.

Retailers spend millions of dollars marketing contrived cultures around their brands: the right music playing in stores, fake vintage books on haystacks, a waft of vanilla as customers browse for jeans.

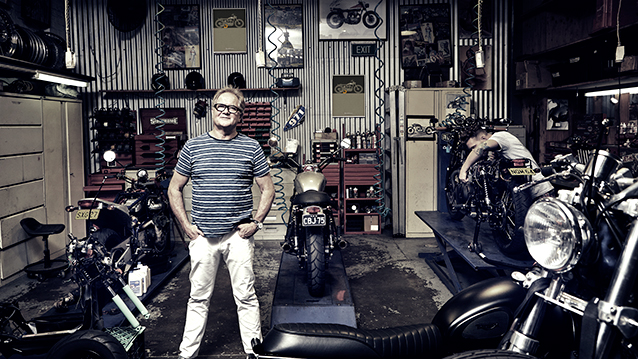

Come weekends, the Deus Camperdown store on Parramatta Road, dubbed “The House of Simple Pleasures” is packed with families sipping Di Lorenzo coffee.

Every couple of months, adjacent Barr Street is full of Yamahas, Kawasakis and Triumphs as riders assemble to test-ride machines, listen to some live tunes and enjoy pork sandwiches off the spit.

“To me, it’s just instinctive,” says Jennings of his approach to business. “A lot of people give that lip service then don’t do it very well, but to me that’s just what the surf industry always was – it was about surfing and the other businesses fed off it.”

Jennings despises words like “lifestyle” and “streetwear”, preferring to define his fashion line as “clothes I’d want to wear”. But he is relaxed about letting Deus mutate.

After all, who could have predicted the Sydney cafe would become a sanctuary for new mothers after appointments at Royal Prince Alfred Hospital up the road?

“The breast-feeding mothers were not in the plan,” he laughs. “I’m keeping it loose because I like the idea of it evolving into different things. If you over-define it, you’re stuck there.”

According to colleagues, Jennings has always maintained a good balance between managing creativity and the bottom line.

With Mambo, he celebrated the work of at least 12 artists, endorsing them through T-shirts and merchandise.

Mombassa says: “I would actually describe him as a renaissance duke or pope, in the way he supported artists, bought their work and put it on shirts.”

Likewise, the success of Deus is in no small part due to his partnership with graphic designer Carby Tuckwell, a part-owner of the business.

It was Tuckwell who invented that now familiar four-letter scrawl seen on shopfronts, surfboards and customised motorbikes.

When Jennings isn’t jet-setting around the world, the two sit across the room from each other in Sydney – engaged, says Tuckwell, in a constant dialogue.

When Jennings opened the Camperdown store in 2006, he didn’t have much to sell at first apart from the bikes and a few T-shirts.

“We had vintage bikes in there and I had inadvertently created a museum … all these old baby boomers turned up in droves. They didn’t want to buy anything, they just wanted to look,” he says.

In spite of protestations, he added pushbikes to the mix. It was good timing: the single-speed, fixie culture was starting up and kids were interested.

“It was young kids who had never picked up a spanner in their lives, who had always just had computers; suddenly it was cool to find some parts and build a bike. It was artistic.”

Deus was being noticed internationally, even then. “We started to get lots of attention, because you can build a motorcycle, put a picture on the internet and people in Finland can see it ... we started to get interest from around the world.”

Interest is one thing, but it doesn’t amount to sales. “I figured out pretty early there was never going to be much money in building motorcycles and bicycles, but if you could use that as a cultural platform, the sky’s the limit with apparel.”

Certainly, as the Deus clothing line grew, so did the rumours about good coffee in the café. “So suddenly this idea was working: the relationship between the things [coffee, bikes and clothes]. I figured what I wanted to do was have all these things stand together, but they should also be able to stand alone.”

He was careful not to make the shirts souvenirs for the bikes – a lesson he learnt early on from his friend Nick Kelly, co-founder of the clothing label Industrie.

“Together they would be stronger, but if you took one out they would still work – I didn’t want the cafe to be a themed cafe, I didn’t want the motorcycles to be props for the clothing.”

As Sydneysiders will attest, Parramatta Road, Camperdown, is hardly a buzzing retail precinct. Nor is it a thriving cafe community. But Deus stores never appear on the high street.

Instead, they pop up with an unfamiliar address in some sparse locale. It’s part of the entrepreneur’s “build it and they will come” strategy. Jennings knew the Camperdown address was no luxury hotspot, but he learnt a valuable lesson early on.

“I discovered space is the new luxury and if you have space you can create an environment that is fun and interesting,” he explains. “You can fill it with interesting stuff so that people make the effort to go there. But you need the food, the stuff: it’s gotta feel like something is going on.”

People are drawn to like-minded people and with Deus, Jennings created a community. “You can walk in and feel like you can learn something here, meet people, something interesting can happen and that’s a really critical part.”

With the Camperdown store doing well, in 2011 Jennings decided to open a store in Bali. “In Bali you get motorcycles and surfing and I knew I could build something pretty wacky at a much lower cost. Plus Bali is a window to the world – far, far more than Sydney could be – and you’re much freer to do things,” he says.

He bought a substantial post, which he likes to call a hipster’s industrial complex, and following his penchant for store names, dubbed it the “Temple of Enthusiasm”.

Like the Sydney store it has a restaurant, but it’s become its own creature with an art gallery and photo studio.

Bikes and surfboards are made on-site and part of the space is used as an artist’s refuge, with an artist-in-residence program and surfboard shaping lessons part of the mix.

“For some reason this global idea was sort of fascinating for me. I mean, kind of stupid in some ways, living in Sydney and wanting to deal with the world. But Bali sort of gave us that because the tourism that goes through Bali is just extraordinary.”

Last year Deus built “The Emporium of Postmodern Activities” in Venice Beach, California. The US was an important market for the entrepreneur, whose first fashion brand had fizzled there.

“I really wanted to do America and I wanted to control America,” he says. “I’d had no luck with Mambo there – no one got it, they didn’t understand it. We sold some T-shirts, but that was it. I figured if we’re going to do it, we should do it. Here we are, this is what we do, you can see it, you can understand it.”

He ignored advice to set up in Orange County, opting instead for Venice Beach, the home of 1970s Dogtown skateboarders, surfers and pot smokers.

“It was everything I loved about America,” he says. “People said, ‘America’s got everything, why would they be interested in what we do?’ But for some reason it’s perceived as being fresh.”

When Deus’ general manager, Ben Monroe, met Jennings at a birthday party in 2004, he was drawn to his fervour. “He showed an enormous amount of enthusiasm,” Monroe recalls. “It was kind of like when you’re young and you’ve met a really cool friend and they suggest going camping to this cool camping spot. That’s the vibe I got, so I went with it.”

Certainly, when Jennings talks about his plans for the brand’s global expansion, it’s hard not to get caught up in the excitement. When discussing Europe he is particularly animated.

Two or three years ago, when Jennings was thinking more about the northern hemisphere, a friend told him to call David Bonderman, who runs private equity firm Texas Pacific Group.

“He said, ‘Give Bondo a call. He’s always up for something new.’ So I called Bondo and he said, ‘you must call Federico Minoli’.”

Federico Minoli is an Italian-born merchant banker, famous for turning motorcycle brand Ducati around when it went bankrupt in 1996. “In the motorcycle community he’s a saint,” Jennings says.

“So he gave me Federico’s number and I thought, ‘oh god, he’s not going to be interested’, but I called him and he goes, ‘Oh, I was hoping you’d call; we talk about what you’re doing all the time. Look, could I come down to Sydney and visit you? I want to bring a few people’.”

Jennings loves this story. “You can always tell if people are interested in what you’re doing if they can be bothered to come and visit you. It’s an important step and the fact that he was coming to Sydney to visit was almost like a royal visit. It was really satisfying for me, because in the motorcycle community we were kind of dismissed as lightweight or not important by people who own Ducatis or Harleys.

“When [those people] found out they were coming to Sydney to visit us, it was like, ‘whoa, not possible!’. That was kind of cool.”

The crux of the story is that Minoli asked if he could put together a consortium of people to set up Deus in Milan. “They wanted to open a restaurant, get a group to create the same sort of environment we have in Bali and Sydney – and by that stage Venice Beach.”

“The Portal of Possibilities” opened in March in the Isola region of Milan, and proved to Jennings that Europe was now a possibility for expansion – as was licensing other stores around the world.

According to the company’s licence agreement, the images, fixtures, art direction and architecture are stylistically managed from Deus HQ.

“However, there is also a consciousness that each Deus licensed store requires consideration and incorporation of local attributes, personalities, culture and aesthetic,” the agreement stipulates. “These are incorporated in different ways specific to each project.”

Says Jennings: “As an Australian, to open a business by yourself in Milan would be suicide. In Italy, doing business is a science best left to the locals. We don’t give them a blueprint; we sit and discuss it. If the guy says I’ve got a chef who does Moroccan food, we might do Moroccan food. It could be fine dining. It doesn’t have to be anything [in particular], but it just should be very good. It just has to challenge the idea. And the more people who walk in and say, ‘Huh? I thought it was a motorcycle place…’.”

The Milan store has also shown Europe – including motorcycle nations of the world such as Italy and Germany – what Deus is capable of. “Since opening in Europe all the Europeans are going, ‘shit, this actually could work’ and suddenly we’ve been getting a lot of requests from people wanting to do something similar.”

Deus distributes its clothing range to stores in 38 countries, including Bloomingdales and Nordstrom in the US. Because the line appeals to so many different consumers, it can be challenging to manage.

Most clothing brands fall under certain categories, such as surfwear, menswear or fashion. Deus ticks all those boxes.

“Deus can speak to a department store customer base, a surf customer base, lifestyle, menswear, and the target audience can be anywhere from a young 18-year-old who likes our cleaner silhouettes through to an 80-year-old who really likes motorcycles or the cut of a long-sleeve shirt that we offer,” explains Varts.

For Deus to welcome new licences will depend on the right venues and the right partnerships. “Quite seriously, we have offers from nearly everywhere, from people who want to do something,” Jennings says.

“We have a fantastic offer from Paris – this amazing restaurateur, a great retailer, a great logistics person and young guy from the surfing industry. On one hand I’m like a kid. ‘Paris: let’s do it!’ But once you get past the romance of Paris, you’ve still got to do it.”

While global expansion is exciting, at the same time Deus is looking at opening smaller retail stores in Australia that just sell clothes and have a cafe component, without the bikes. The aim of these stores would be to attract higher foot traffic.

The second Deus Sydney store – a hole-in-the-wall cafe and clothing hub – recently closed after a problem with the landlord. Deus is now testing a site in Byron Bay.

Says general manager Ben Monroe: “There’s a finite number of resources, such as cash and people, to do business with. A lot of it is being directed internationally at the moment, so there’s the balance between domestic operations and pushing international relationships and opening up new markets.

“We can either become a specialist franchise and open up shops around Australia or we can push international distribution and open shops and franchises later on.”

With everything that’s on the horizon, Jennings has made one thing very clear. No two stores need be the same.

“My take on all of this is I always hated how you could go to a Prada shop in Milan or Helsinki and it will always be the same. I never saw the point of that. Deus is an idea and the point is to take the seed and plant the seed in different soil and it will manifest itself differently… it should represent its environment, not be this cookie cutter that works around the world.”

If there’s one thing you notice about Deus employees, it’s that they practise what they preach. Most of Jennings’ staff share his passion for surfing, bikes, good food and music.

In Bali and California, the working day usually begins in the water. “It’s not a prerequisite,” jokes Varts, “but it’s something we’re all passionate about and I think that’s why the brand is achieving so much success at the moment. We believe in what we’re doing. If someone is selling a brand they don’t really believe in, you can sniff that out pretty quickly.”

Jennings is aware, of course, of the fall of like-minded Australian fashion labels such as Billabong and Ksubi. “I mean, failure is ever-present of course, but the difference between my two businesses is that with Mambo I had nothing and built it up bit by bit. With Deus I was cashed up because I had sold Mambo and could do what I wanted to do. The trouble with that is that you create this overhead and you don’t have the revenue to match it.”

With annual revenue of A$10 million to A$15 million, Deus is profitable but Jennings believes it still has a long way to go. “It hasn’t worked yet. But it’s working – it has massive potential as a serious global brand that does a lot of varied things,” he says.

Jennings realises he may not be around forever. “I’ll have to construct it differently ultimately, because it will require more money,” he says. “Once I’ve got a stronger platform I can get other people to do things and hopefully I can be the grand old man of the whole thing.

“But we’re the ‘dying with our boots on’ kind and the idea of retiring is just a horrendous thought,” he says. “Certain words take on new meaning as you get older and retirement just sounds like death.”

Of course, when that time does come, his team will ensure that what happened with Mambo doesn’t happen to Deus.

After Gazal bought Mambo, the new owners ditched the farting dog and other trademark designs in an attempt to make the brand relevant to a younger audience.

Ultimately the strategy failed and it took the Nervous Investor Group buyout to resurrect the brand.

Monroe says it’s unlikely anyone would let the sale of Deus – should that happen – change its blueprint. “We’ve all learnt a tremendous amount from him and if staff were to remain they would certainly take a plan of attack similar to what Dare has taught us,” says Monroe.

“We know at the end of the day the bikes are the plan, not the data sheets of profit and loss and whatever else. People don’t buy T-shirts because there’s a black number on the bottom line of a data sheet, they buy it because of what the creative stands for.”

A few days before he flew into New York, Jennings stopped off in California at the Emporium of Postmodern Activities. Although it was not dissimilar to the community he has watched flourish around the Sydney store, Jennings was surprised by what he saw.

“It was kind of what I had hoped, but not dared to think was possible,” he says. “I was there on a Saturday and there were hundreds of people. It was all about surfing and motorbikes, and it was also about very cool people and bands playing in our carpark, plus these Mexican guys roasting pigs for us. It was so cool and exactly what I wanted it to be. It was wonderful to see it come along like that.”

One could say doing what he loves has paid off. “It’s a grand adventure and in the end it has to be an adventure.

“I’m not sure where to go, but it’s predominately about the fun of trying to get the idea to work.”

Top gear

The Australian fashion landscape was dramatically changed by surfing culture in the 1980s and 1990s.

People were drawn to the romantic notion of freedom that surfing represented and brands capitalised on that with apparel, Jennings says.

Surfwear, peddled by brands such as Quiksilver, Billabong and his own company, Mambo, took over from menswear as the fashion of choice.

What Jennings terms “scruff culture” became more readily available, and more acceptable too with men sporting worn-out T-shirts and ripped jeans as everyday wear.

It was the start of a new trend known as “guys who dress badly” which, funnily enough, helped put Australia on the world fashion map.

“Australia can never really compete in the true fashion world – there’s no industry here,” says Jennings. “It’s all done in the northern hemisphere so the only way we can compete is to create a culture to sell apparel.

“That’s what I’m trying to do with Deus. We’ve created this culture, this idea and now we are using that to take it to the world. Apparel will be what we use to carry it.”

Jennings’ business mantras

Give people what they don’t know they want

The late Apple chief, Steve Jobs, was famous for saying “a lot of times people don’t know what they want until you show it to them” and Jennings follows the same school of thought.

“Henry Ford said if he’d asked people what they wanted, they’d say a faster horse. You can either have ideas and try to get your ideas to fly, or you can copy other people and compete on that level.”

Do what you love

“[With Deus,] I wanted to draw on my experience so far, do something that was kind of a progression from where I was, from what Mambo had been,” Jennings says.

“And I wanted it to be about motorcycles, because I’d always loved motorcycles and I just feel that motorcycles were this wonderful, romantic idea. They carry a massive emotional appeal – especially for men, but not only men.”

Don’t listen to negativity

“If people tell you that you can’t do something, that’s when you should do it,” Jennings believes.

By challenging people’s notions of what’s right or what works, you’ll make them sit up and notice.

“Even if they feel like they hate you, they will come back – and will keep talking about it.”

Do the opposite to everyone else

Jennings realised having retail space was the new luxury.

Why stick your store next to everyone else’s when you can have a bigger one all on its own? Build it right and they will come.