Loading component...

At a glance

Updated: 31 August 2016

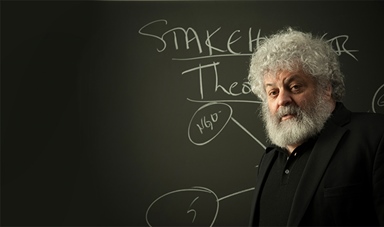

He jokes that he looks like Karl Marx, then talks about the need for business profit. But the man behind the idea of business stakeholders has spent three decades shaking up our ideas of “value”.

If you have ever talked about a company’s “stakeholders”, you owe some small debt to R. Edward Freeman, the bushy-bearded inventor of stakeholder theory. Before Freeman’s 1984 book Strategic Management: A Stakeholder Approach, almost no one in business talked about “listening to our stakeholders”.

Yet within a few years of the book’s publication, everyone understood what stakeholder language meant, and today almost everyone uses it.

Professor Freeman’s point was that business theory pretty much saw managerial self-interest and shareholder profit as the driving forces of business. But that wasn’t the view of the people who actually did business. Instead, they had other motivations and responded to other people: employees, customers, suppliers, regulators, industry bodies, trade unions, community groups. Freeman called these groups “stakeholders”.

Freeman has been developing his business philosophy for more than three decades. Despite his plentiful achievements so far, he describes himself as a lifelong student of philosophy, martial arts and the blues. When he talked recently with CPA Australia, he tackled head-on what he calls “the old story”.

This is his name for the idea that people in business focus only on profits and shareholders, and that they are “greedy old bastards that are trying to do each other in”.

Freeman’s new story is that businesspeople are – and always have been – interested in far more than profit. You still need to make money: “businesses have got to have profits to live”, he readily agrees. But money-making is not the purpose of business, he argues, it’s merely an outcome.

“Entrepreneurs start businesses because they want to change the world somehow,” he says, pointing to individuals like Microsoft co-founder Bill Gates. And to succeed, businesses must give something to many different stakeholder groups:

“You want to have a successful business, you’ve got to have great products and services for customers, you’ve got to have employees who show up and who are there and want to help make it better. You need suppliers in today’s world who want to make you better because working with you makes them better and vice versa.

"You need to be a good citizen in the community because in free societies and the age of the internet, you’ll get regulated out of existence if you don’t do that.

“And if you do those things, you’re going to make money.”

Freeman acknowledges that different stakeholders’ interests often push in different directions. For years he talked of finding the balance between interests. These days, he has a better metaphor: businesses must work to “harmonise” their interests.

"People are not willing to turn loose of that idea that it's only the money that counts."

“In harmony the notes are different but they sound good together. Stakeholder interests are different but the idea is you want them to work together, to sound good together – even when there’s conflict … When you find conflict, that’s a place where you can create value, so you have to think about stakeholder interests and where the conflict is – not in a balancing or trade-off sense, but in a value-creation sense.

“Some stakeholder says ‘I don’t like the way you do this’, and one response is, ‘Well, let’s figure out how to do it better’ … You want feedback so you can become better, so you can figure out how to create more value.

“So that’s the way I see that now: not as a matter of keeping things in balance, but as a continual growth process of harmonising and reharmonising and reharmonising again.”

Stakeholders signal value

But when Freeman talks about creating value for stakeholders, what does he mean? He argues it’s a mistake to restrict the idea of “value” to just financial value. He wants instead to use value to encompass all the things that customers, employees and other stakeholders find valuable.

“This is a big area where accounting has a lot to offer,” he says.

“You get value out of your smartphone. Now, part of that can be explained economically. But part of it can’t be explained economically.”

For instance, he says, you get the value of being connected to your friends. “I don’t need to define that … I think the problem with value is we try to financialise all of it. That’s a mistake, that’s not who we are as human beings.”

“I think we create value when we do things that people find valuable.”

Can you put a number on it?

One great strength of the traditional shareholder-centred view is that it gives you firm numbers to work with. Profit, enterprise value added, earnings per share – these are all hard measures of a firm’s performance. Stakeholder value also matters, but is it something you can measure?

Freeman studied mathematics as well as philosophy in his first degree, and he is keen to give stakeholder theory some numerical rigour. He himself asks the question: if you wanted to help a company figure out how to create value for its stakeholders, what kind of things would you look at?

“Companies have some of this already,” he responds. “Every good company knows the indicators it needs to find out whether they’re creating value for customers or not.”

But in other areas, value indicators are less common. Companies rarely know the value they create for their employees, for instance, and when they do, they often find they’re doing badly. A 2013 Gallup report found that only 13 per cent of workers felt engaged by their jobs.

“The numbers are stunning,” says Freeman. “There’s a lot of work to be done here [on what] to think about that.”

We have similarly poor measures of the value that companies create for the community, he argues, and even measuring perceptions over time would be better than nothing.

“These aren’t hard questions,” he says. “I’m unimpressed when people say, ‘Well, that’s a tough measurement question’. No it’s not. We put somebody on the moon and brought them back. I mean, this is not a hard question. People are resistant to it because the ‘old story’ kind of has their brains in a death grip and they’re kind of not willing to turn loose of that idea that it’s only the money that counts.”

"Entrepreneurs start businesses because they want to change the world somehow."

Freeman jokes about his resemblance to Karl Marx, that other stocky, heavily bearded thinker about business. As he tells it, Freeman too believes in revolution. But he wants a revolution in ideas: that it’s not all about competition, greed, self-interest, and a willingness to do whatever it takes to maximise profits for shareholders. He believes profits are merely a necessary outcome of business; they are not its sole purpose.

Changing accounting

Accountants have a role to play in Freeman’s stakeholder-dominated view of the world:

“Accounting as a field has focused on financial accounting ... People talk about social and environmental accounting and I think those, again, accept the old business model: ‘There’s the finance and then let’s bolt on social and environmental’.

“I want to change the business model. What kind of accounts would you keep? How would you think about accounting if you thought you needed to figure out how to create value, not just for investors but for customers, suppliers, employees and communities and [the] people with the money? That’s a big question, it seems to me, and one that will require a lot of thinking by people who know a lot more about accounting than I do.

“Let’s suppose I’m a potential employee and I want to understand whether I join this firm or not. What are the things I should look at? And furthermore, if I’m the manager and I want to figure out how to create value for employees, what are the indicators that I should focus on?

“Some of those indicators might be already in the generally accepted accounting principles. Our preliminary thinking, however, is that probably some of that has to change.”

Freeman on the 'business case'

“If you say I want the ‘business case’, you’re talking to me from the old story. You’re saying, tell me that this makes money, right?

“So if by a business case you mean: does this pay financially to shareholders?' then say that, but that’s not what a business is. A business is something broader. Having said that, it is absolutely clear to me – and I don’t know how anybody can ever question that if you create a lot of value for customers, suppliers, employees, communities – you’ve got to create value for people with the money.

“It’s not going to be a trade-off of one versus the other, especially if you try not to make trade-offs. The companies that do this are going to beat the pants off the companies that don’t. There’s some preliminary research that companies who take the stakeholder approach, outperform standard market indicators by something like nine to one.”