Loading component...

At a glance

The great paradox about earth-shattering infrastructure projects is that the very best of them step lightly, go unremarked and are largely ignored. In the infrastructure space, success takes the form of quiet achievement.

Wayne Reaburn FCPA is a firm advocate of this approach. As director of finance and administration at the Melbourne Metro Rail Authority (MMRA), he knows that the faster projects merge seamlessly and cost-effectively into the landscape, the better for everyone. It sounds good, but is a quick and quiet reconfiguration of a metropolis even possible?

Urban upgrades and refurbishments, enlargements and spatial changes are all part of progress, but for many they spell one or more of these: traffic disruption, cost overruns, countless delays, stakeholder and community dissatisfaction, political interference and press sniping.

Reaburn is now a couple of years into the running of Melbourne’s Metro Tunnel, an A$11 billion underground rail project, and most of the preparatory work has been done. All seems relatively quiet at the moment but the big dig is yet to begin.

The end game is 2026, when Melbourne will have twin 9km railway tunnels replete with five new underground stations. It’s the biggest single investment in public transport Victoria has ever made.

Learning curves: Myki and Regional Rail Link

Reaburn is no stranger to the problems that hamper large operations. He was involved in Melbourne’s A$1 billion Myki public transport ticketing system, which was bedevilled with cost problems and technical issues for much of its drawn-out implementation.

He arrived two years into the Myki project. “For the first six months everything seemed fine. Then the first major milestone came and went, and it became progressively more clear that the project was going south in terms of time and budget,” he says.

“Having your project on the first few pages of the newspaper is invariably not a good thing.”

Victoria’s auditor-general reported in 2015 that, in all, Myki took nine years to fully implement (it was originally seen as a two-year job), with the overall cost blowing out by around A$550 million, or 55 per cent.

Reaburn says sooner or later everyone in the infrastructure space gets “a Myki-type project, but it’s a real learning curve and you get to see first-hand what good project management looks like under the pump.”

His accounts had to be qualified in the year Myki was launched, due to auditor concerns about the veracity of revenue numbers from the system.

“My team was able to help quickly turn this around, working intensely with the lead contractor to ensure the system was capturing all transactions end-to-end. That was no mean feat with a micropayments system as complicated and transaction intensive as Myki,” he says.

It is this kind of micro-detailing that Reaburn will have to apply – times a hundred – to the Metro Tunnel project.

He may have Myki on his CV but he also has the highly successful A$4 billion Regional Rail Link. The project was completed under budget and ahead of schedule in 2014, and won the Infrastructure Project of the Year in 2014 and an Australian Construction Achievement Award in 2015.

“And it got very little press,” Reaburn says, with a laugh.

Stakeholder management and a multilayered governance framework

In contrast, the Metro Tunnel is hardly likely to escape the metropolitan news radar. Melbourne’s rail system badly needs upgrading to deal with a quantum leap in passenger numbers.

The MMRA’s role covers the entire project lifecycle, from project approval through to tender evaluation, contract awards and construction. It also includes the acquisition of about 80 properties. Project management and oversight are vital tasks but so, too, is stakeholder management.

Reaburn says there are about 45 governance and stakeholder forums with which the MMRA regularly interacts. Since early 2015, 379 submissions have been received regarding noise and vibration from tunnelling, changes to traffic and transport, loss of trees, impacts on open space, local businesses and the possible destruction of heritage areas.

There’s also the governance framework which is multi-layered, far more than any comparable private sector project.

All that has to be dealt with even before breaking ground. Asked how he keeps on top of this, Reaburn says he has a great team “that simply deals with the problems as they crop up”. A project team worth its salt is one that enjoys solving issues as they arise each day.

“Our mandate is clear. We have to deliver the tunnel on time for A$11 billion. We break it down into thousands of line items so we can keep control at a granular level. We budget those, we report against those and we forecast monthly on a line-by-line basis,” he says.

Strategy for success

Reaburn says he has been able to implement a “best for project” information and communications technology (ICT) strategy, largely uncompromised by an outdated legacy ICT environment.

The key elements of the strategy have been to procure cloud-based project applications that meld into a digital, user-friendly workspace.

“It’s anywhere, anytime systems access for our people, internal-external collaboration spaces, and in-house capability to optimise value for money,” he says.

"Our mandate is clear. We have to deliver the tunnel on time for A$11 billion."

At the heart of the IT strategy is Office 365, which the team uses in tandem with the cloud-based software for project-specific requirements.

“Using Office 365 is not new, but having no legacy systems means we have been able to optimise use of the suite of Office 365 applications to create a seamless, integrated working environment.”

Another strategy is to give his team 20 improvement goals at the start of each financial year.

“In our space it can feel like everyone else has clear objectives and is charging forward, but for us it’s different – our team is on a treadmill of monthly reporting cycles. However, with the benefit of a such a long-term horizon, we have the time to innovate how projects like ours and future ones are supported.”

The problem with optimism

Perhaps the strategy Reaburn would like to be known for is his take on managing budgeting and forecasting. To accurately forecast project costs, he says you need to understand the “optimism dynamics” of an organisation.

“The downside to optimism bias is that it creates a propensity to overly positive assumptions that can lead to major miscalculations, particularly for large infrastructure projects,” he says.

Reaburn cites the work of Professor Bent Flyvbjerg from Oxford University’s Saïd Business School, who in 2003 looked at 258 rail, bridge, road and tunnel projects around the world valued collectively at US$140 billion. Flyvbjerg found that 90 per cent of these projects went over budget due to optimistic forecasting.

“For big tunnel projects like the Melbourne Metro Tunnel, history says the overruns are the worst,” says Reaburn.

The research states the average cost overrun for a rail tunnel project globally is a whopping 45 per cent. Typically, the cash flows are also wrong, with spend lower than expected in the early years and higher in the later years and beyond, as the project takes longer to mobilise than expected. Reaburn is clear this won’t be happening on this project.

The strategy to keep forecasts real has as much to do with the numbers as it has with the way humans think.

From his experience in the private sector, Reaburn knew which of the branches of the operation were likely to give him optimistic budgets and which would take more conservative views.

“From this we could normalise their input into a realistic target,” he says. “We took this to the next level by tracking the accuracy of monthly forecasts versus actual results. We have in the past used this to provide feedback to poor forecasters, which led to marked improvement in some cases.”

Cost oversights and poor forecasting versus actual results are anathema to Reaburn. He stayed committed to coming in on budget on the Regional Rail Link, and the Metro Tunnel should be no exception.

Do it right and it’s a quiet ride … and that, of course, is the grand aim. The best strategy for world-shattering infrastructure is to keep calm, stay focused, and not get too exuberant too early. Reaburn, like the huge project he helps to run, wants to be the quiet achiever.

The great Metro Tunnel rail project

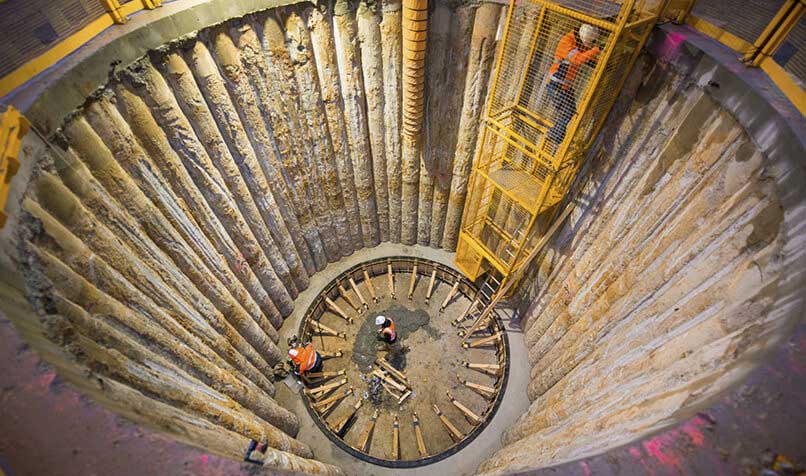

Construction of the Metro Tunnel is expected to disrupt Melbourne for several years, as eight roadheaders and four giant tunnel-boring machines scrape the crust below the CBD.

The project gives the impression that Melbourne is shifting its own geography. There will be new stations at North Melbourne, Parkville, Town Hall and State Library, and Anzac Station in the Domain. The current North Melbourne station will be renamed West Melbourne to reflect its location, with a new North Melbourne station to be created in the Arden-Macaulay development precinct.

The venture features wide platforms at the five new underground stations, including an entrance at the doorstep of the Royal Melbourne Hospital, while underground walkways will connect to platforms at Flinders Street and Melbourne Central stations, allowing passengers to transfer to City Loop trains.

The project is so large it has to be divided into four key packages: early works, the tunnel and stations private-public partnership, the rail systems alliance, and the rail infrastructure alliance.

Early works began with procurement in 2015 and construction got underway in 2016. The tunnel and stations partnership, and the rail systems alliance contracts, were both awarded late in 2017, with tunnelling to start in 2018. Contract awards for the rail infrastructure alliance will occur later in 2018.

What makes Wayne Reaburn tick?

“I have been lucky to work with and for some great people in both public and private sectors. Not all of it has been clear sailing; I have been inspired by the ability of leaders to continue to positively strive for the best outcomes in adversity,” says Wayne Reaburn.

“Working in a number of industries has also honed my understanding that good management practices, particularly financial, are universal and readily transportable to new environments. I like to think I’ve also learned what good leadership looks like, to see the bigger picture and readily identify opportunities for improvement.

“Sport has also been a big part of my life, and has taught me the need to be an effective team player. We don’t have to be best buddies but we need to look after each other to get the best result.

“I’ve also been fortunate to play at a great club (the Brunswick Cricket Club) where there are outstanding examples of determination, humility, remaining positive and continually striving to improve.”