Loading component...

At a glance

It’s lunchtime on a chilly winter Wednesday. On the shores of San Francisco Bay, the Team Strava Run Club is going through its Workout of the Week. Around 40 people, a quarter of Strava's total workforce, are doing timed interval training: run hard, rest, repeat. There is laughter and banter, clapping and cheering. There, running with the pack, is CEO James Quarles.

Later, back at Strava HQ, they’ll fire up their fitness tracking app to check the club’s digital leaderboard or their personal Suffer Score – a rating invented by Strava to “measure how hard you try”. However, for now, the Strava team is happy doing what it loves best: testing their physical limits in a community of athletes.

For Quarles, this sense of shared experience is Strava’s secret sauce.

“Community is our core,” he says. “People say they don’t download Strava, they join Strava.”

It’s also at the heart of the company’s ambitions for the future. Quarles says Strava’s aim is “not to be the global leader in digital tracking … it’s to be the best sports brand of the 21st century.”

To do that, Quarles and his team will need to take Strava to places it’s never been before.

The business of sharing

Quarles is no newcomer to the business of making digital communities commercially successful. From 2011, he spent more than three years with Facebook as regional director for Europe, the Middle East and Africa, growing the company’s advertising revenue and “humanising the brand”. After that, he was vice president of Instagram Business, where he helped transform the photo-sharing platform into an advertising powerhouse.

“It’s been great to have been on a couple of different rocket ships,” he says.

His time at Instagram was one of phenomenal growth, with the number of active users surging from less than 300 million a month when he joined to about 800 million a month three years later. Meanwhile, he helped the company create an advertising business from the ground up.

“When I joined it in 2014 … the business didn’t exist. It was an incredibly fast-growing product, but my role was to work with the co-founders, Mike Krieger and Kevin Systrom, on building [an advertising] business that was very tailored to this product people were in love with, and not making that feel like it was any trade-off,” says Quarles.

The secret was to never lose sight of the company’s original mission. “You have to have a North Star,” he says. “Success at Instagram has come from a discipline. It’s been an ever-present discipline to keep things simple … and that has meant a number of choices of what not to put in the app.”

It also means maintaining “a level of care and thoughtfulness” not always common in larger corporates.

“When we started the business of having advertising, Kevin, the CEO, and I would sit down and review ads, every one of them, before they went onto the platform,” says Quarles.

“The team was very intentional on what messages [ran] and how well they fitted into the Instagram experience.”

Planning his route

It’s no accident that Quarles’ career has taken him to increasingly senior roles at progressively smaller companies.

“I think as much as one thing can be deliberate in your career, that probably has been,” he says.

He’s been driven by a passion for finding the pathway from a founder’s original vision to ongoing growth and, ultimately, commercial sustainability.

“It’s very hard to build a product or a service or community that people love. That’s what great founders and entrepreneurs do,” says Quarles. “However, it’s equally hard to turn those great ideas into long-lasting global companies.

“There’s an important step in that process … of trying to deduce what’s working and why, and really invest [in] it, and unlock it and open up its potential.”

That’s where Quarles’ experience is invaluable. “I did it at Instagram, I’ve done it here: understanding a company’s superpowers and really trying to make those distinctive and ownable.”

Looking beyond the leaderboard at Strava

If you run or ride, you’ve probably heard someone say, “If it’s not on Strava, it didn’t happen.” It’s a phrase you’ll see on T-shirts and hear on cycling routes around the world. Now, Quarles wants to take it into the pool and the gym, too.

“We want to be the place where Strava becomes the home for your active life, and that means an increasing emphasis indoors, on the other 55 per cent of what people do,” he says.

“Going to studio classes, training at home … we want all of those to count and to be a part of the Strava experience.”

Strava already syncs to more than 300 compatible devices, from Garmin activity trackers and smartwatches to Fitbits. Now, it is increasingly adding indoor machines and training experiences to its list of partner integrations.

“That is a big strategic priority for us, working with indoor partners such as Flywheel Sports, Peloton, Zwift [and] LiveRowing, to make sure that when you record [exercise] with those partners, the activity shows up in Strava, just like your run would or your ride would,” says Quarles.

“That list will grow significantly over this year.”

"People say they don't download Strava, they join Strava."

Quarles and his team are also exploring new ways to support every aspect of its users’ active lives. “We’re doing quite a bit of very active research, both statistically and ethnographically, to understand our athletes as best we can,” he says.

One important insight has been the frequency with which people take time out from physical activity – whether that’s because they’re sick, injured, pregnant or simply busy.

“They’re really tough periods for people who just have such desire to be out doing the thing that they love,” says Quarles. It’s also a conundrum for Strava, whose customers are only visible to the company when they’re training.

“They’re not going to show up on any of those leaderboards,” says Quarles. The company is asking, ‘how can we also be there for them through the hard times, when they have to go back indoors, maybe they’re on a trainer, maybe they’re reducing their time and distance?’

Growth at Strava: feeling the heat

Strava is growing fast, adding around a million new users every 40 days. Yet while scale is essential to sustainability, it can also bring challenges of its own.

That’s something Quarles learned at Instagram, where growing popularity increasingly attracted attention of the wrong kind.

“The Instagram team identified and has been conscious of the product and the brand’s role in society, and that has particularly related to negativity that’s emerged in social media, where there are trolls and just an increasing tendency for people to not behave very civilly,” says Quarles.

Instagram took the decision to “proactively stand against trolling and negativity”, adding a customisable comment filter and, more recently, an artificial intelligence-powered spam filter and troll blocker.

At Strava, the app’s increasing ubiquity created a very different problem in early 2018, when it released an interactive heat map of its users’ fitness activity. Bringing together one billion activities and 13 trillion GPS data points, the heat map enabled anyone to explore popular exercise routes across the globe.

At first, it seemed to be a publicity coup. Then, an enterprising Australian university student, 20-year-old Nathan Ruser, “noticed the map showed the locations and running routines of military personnel at bases in the Middle East and other conflict zones”, according to the Australian Broadcasting Corporation. As a result, it revealed patrol routes, the locations of secret bases, and even their internal layouts.

For Quarles and his team, it was an entirely unexpected crisis. They moved quickly to reinforce the app’s already considerable privacy controls, and to wipe sensitive data from the publicly available heat map. Yet Quarles says the company is still suffering from inaccurate press coverage generated by the issue.

“There’s been quite a bit of misinformation,” he says. “Just to explain, our heat map is an incredibly valuable resource for our community. Hundreds of thousands of people use it to plan where they ride and run and swim.

“It’s important for us to make people understand that we’re not background-tracking people’s use. There are explicit records. People have to start, stop and save activities.

“This is not a data breach. We’ve only published public activities that have been uploaded publicly.” He adds: “We don’t sell our data to third parties.”

People first, then profit

Growing Strava’s community of athletes remains Quarles’ number one priority.

“We’re not profitable at the moment. That’s intentional. We think growing the community and becoming the most engaged community of athletes in the world really is the immediate priority, because it creates such optionality for us to build a great business,” he says.

That’s why Strava continues to use the freemium model – which offers a fully functioning app for free, with an optional upgrade to a subscription-only premium version. Quarles says that there are no plans to introduce advertising to the free app.

While the premium app remains Strava’s “primary business line”, Quarles says the company is also pursuing other promising revenue sources.

“Our second business line is called Strava Metro, an insights business where we take the aggregate commute data from bikes and pedestrians, and work with city planning departments … for better infrastructure planning.”

In Australia, the Queensland Department of Transport and Main Roads began working with Strava Metro in 2014 to inform its strategy to build more bike routes and improve ones that already exist.

Strava is also working with businesses including Lululemon and Red Bull to create virtual, sponsored challenges within the app.

“We think that there are great opportunities to bring those brands and businesses more into the experience in a way that improves the community’s love of the product, so we have been and will be testing this,” says Quarles.

Meanwhile, like so many Strava users, he continues to balance work, life and running. Naturally, every activity is tracked on Strava.

“I’m a runner, and a swimmer, and a skier,” he says. “I’m one of those athletes who really is trying to just improve myself.

“I do a habitual 10 or 12 miles [16-19km] on a Sunday morning, and I love watching my improvement … how I’ve been able to just get more fit.

“A lot of that is down to the Workout of the Week. The speed training that my colleagues have helped me do has actually helped me get much faster.”

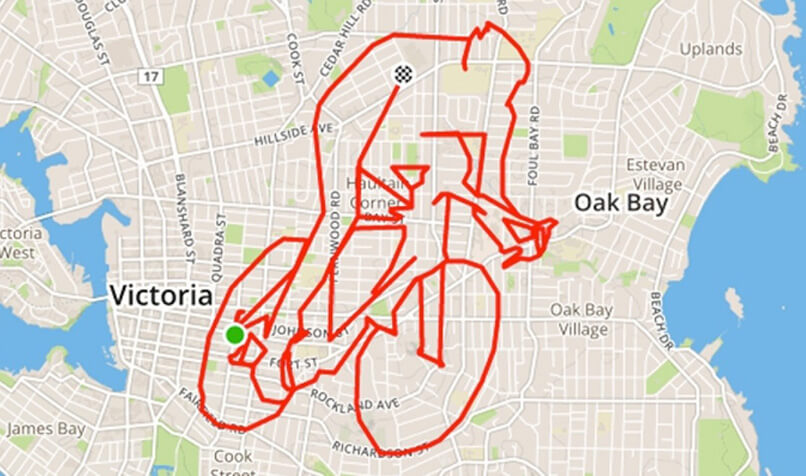

Strava art: Yes, it's a thing

Strava users are running or riding pre-planned routes to create doodles with their tracking.

The big cyclist: By Canadian cyclist Stephen Lund.

The Welsh dragon: A 44km run by Martyn Driscoll and Alan Stone.

She said yes: “Marry me Emily”: a Strava proposal mapped out by San Francisco cyclist Murphy Mack.

Strava in numbers

- Activities recorded as at 31 December 2017: 1 billion

- Runs uploaded in 2017: 136 million

- Marathons uploaded in 2017: 627,239

World records recorded on Strava in 2017

- Kate Driskell ran the length of the UK (1722km) in 37 days.

- Sandra Vi ran 5000km across the US in 54 days, 16 hours, 24 minutes.

- Killian Jornet summited Everest twice in a week, without oxygen, in 17 hours and 26 hours.

- Dianna Chivakos with son Evan ran the fastest marathon while pushing a stroller (3:10:21).

- Ryan Starbuck ran the fastest ever marathon in a crab costume (3:09:42).

Source: Strava