Loading component...

At a glance

Veteran journalist and author Diana B. Henriques remembers Bernie Madoff when he was a radical; the first guy on Wall Street to take up new technologies and trading techniques in the 1970s and 1980s.

The New York Times finance reporter watched from the sidelines as Madoff evolved into an investment titan, sailing through the Black Monday crash of 1987, the tech wreck of 2000 and the horrors of 9/11.

All the while, the funds Madoff managed gained steadily, accumulating wealth for some of the richest people in America.

Henriques, who has been a finalist for the Pulitzer Prize multiple times, admits she never “really” knew him. Nobody did.

He was, she says, the “trusted criminal”. His integrity was considered so unassailable and his chutzpah so magnetic that he was beyond examination.

The investors of Bernard L. Madoff Investment Securities, some of whom were retired heads of global investment banks, all thought he was God’s money manager. So did his accountant, who never audited his assets.

Even the US Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) considered Madoff too big to seriously probe.

Madoff operated the greatest Ponzi scheme in history, losing US$17.3 billion of his clients’ money, but before that he was a former non-executive chairman of the Nasdaq and served on the board of directors of the Securities Industry Association.

He was also a founding board member of the International Securities Clearing Corporation and called former SEC chairman Mary Shapiro “a dear friend”.

When Madoff was convicted in December 2008, Henriques knew instinctively the story wasn’t just about him, but about the way we treat people like him.

It was the beginning of her research into the scandal, which resulted in her bestselling book, The Wizard of Lies: Bernie Madoff and The Death of Trust.

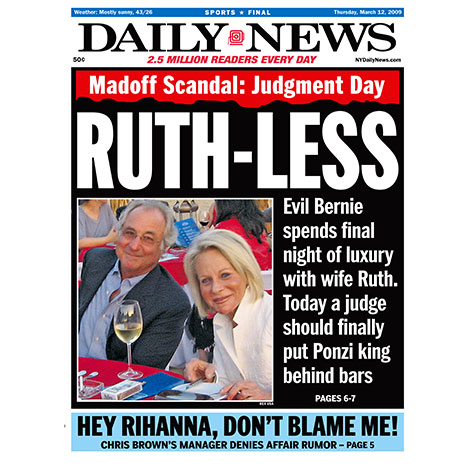

The book was also adapted into a movie by HBO and released in May 2017, starring Robert De Niro as Bernie Madoff, Michelle Pfeiffer as Ruth Madoff, and Henriques playing herself – as the first reporter Madoff agreed to interview him in prison.

“One of the things that concerned me about coverage prior to the book was it painted him as an inhuman monster,” Henriques says.

“One magazine doctored his image to make him look like the Joker [supervillain and archenemy of Batman] – all this gives us false comfort.

“We think we’ll see these guys coming. We think we’ll recognise them before they get close enough to hurt us. It’s wrong. These guys don’t look like the Joker. They look like Robert De Niro. They look like [somebody] you’d want to sit next to at dinner.”

The trouble, she says, all came down to a lack of basic compliance – and scrutiny – by accountants and auditors doing initial checks.

If you ignore the simple checks, she says, legitimacy can be hidden under layers upon layers of untruths and obfuscation.

Like everybody, Madoff ’s accountant David Friehling accepted at face value every piece of documentation from the Madoff firm that came his way. He happily invested with Madoff and recommended his other clients do the same.

Friehling pleaded guilty to securities fraud, investment adviser fraud and making false filings to the SEC. He was also found guilty of obstructing the Internal Revenue Service (IRS), admitting that he had rubber-stamped all of Madoff ’s filings and never audited them.

As Henriques sees it, it was about one rule for the stars, another for everybody else: a situation accountants should eschew on principle.

“Friehling did not do the normal tests, nor demand documentation. He did not apply the normal scepticisms that accountants apply. He trusted Bernie so much, he broke the rules for him,” Henriques says.

“When this happens, these are devilishly hard criminals to catch with normal compliance systems.”

"These guys don't look like the joker. They look like Robert De Niro."

Henriques also points to the legal loopholes that allowed Madoff’s fraud to happen.

Privately run funds such as his were not required to use an independent third-party custodian, which could easily have reconciled the actual assets held with his firm’s stated trades of stocks and bonds – none of which were ever executed.

Firms such as Madoff ’s and hedge funds remain exempt from using an independent custodian, while mutual funds, which hold “mum and dad” assets, are not.

“An independent custodian should be the rule for every money manager,” Henriques insists, “but the small guys complained that it cost them too much, and the big players said they didn’t want their competitors knowing what assets they were holding.

"Eventually the regulators backed down.”

Henriques’ last piece of advice to accountants is to give scope and respect to whistleblowers.

Auditors must be comfortable blowing the whistle because they are the first line of defence against fraud, the most credible people in the compliance chain.

“They [have] an obligation to their professional code, which supersedes whatever loyalty they owe to whomever is signing the pay cheque. If people stop trusting the profession of accountancy, then everybody is diminished.”