Loading component...

At a glance

By David Walker

Angus Hervey has little patience with many technology “thought leaders”. “There are a lot of people out there talking about technology,” he says, “and almost all of them tend to either exaggerate it or dumb it down – or they have a fear message around it.”

Hervey is one of the founders of Future Crunch, a Melbourne-based consultancy dedicated to informed and optimistic thinking about current technology and the opportunities that technology presents.

The head of the Australian Federal Police (AFP) credits the consultancy with helping it to understand how technology can drive strategy. Hervey and co-founder Tane Hunter’s audiences have ranged from MYOB to Interpol. Besides law enforcement and accounting organisations, they have worked with groups in the housing industry, construction, city planning, energy and local and federal government.

“What we do with Future Crunch is try to say what’s actually happening, rather than what could happen or what someone ... says is happening,” Hervey says.

Hunter agrees. Despite the company name, the pair are “not futurists”, he says. Hunter is a biologist, Hervey an economist. Together they aim to explain the technologies that are already available to people – right now.

The pair unashamedly sees technology as a force for good.

Hervey has blogged on the consultancy’s site that he believes optimism is a powerful way to create change, writing that “we should be planning for a future in which things get better”. The more people start believing we can create a better society, the sooner we can start taking action, he says.

The pair will present at CPA Congress, which will take place in Australia in October 2019, outlining why and how CPAs might take advantage of these new services.

“Technology is a layer over everything, and if you’re not engaged in this technology, then you’re not going to keep up,” Hervey says.

“In many cases it’s really trying to get people to break down the fear and change the way they think and assimilate information about technology that can really transform their personal lives and their business.”

Hervey says that at the Congress sessions, the pair will not just show CPA Australia members what the technology is doing, but also provide lists of resources, recommended courses and institutions with particular expertise – a road map for becoming more adept at the powerful emerging tools.

At the same time, the pair jokes that their business model is awful. “No one wants the product that we sell, which is good news,” says Hervey with a grin.

“To fund our efforts to promote good news and create and share it, we talk about science and technology on the side.”

Technological change targets accounting

Hervey, the son of an accountant and a software engineer, calls accounting a “really interesting mix of highly technical and highly human” and says the people side of the industry will only increase in importance. He says technological change often affects accounting early – but rather than disappearing, accounting jobs change their nature.

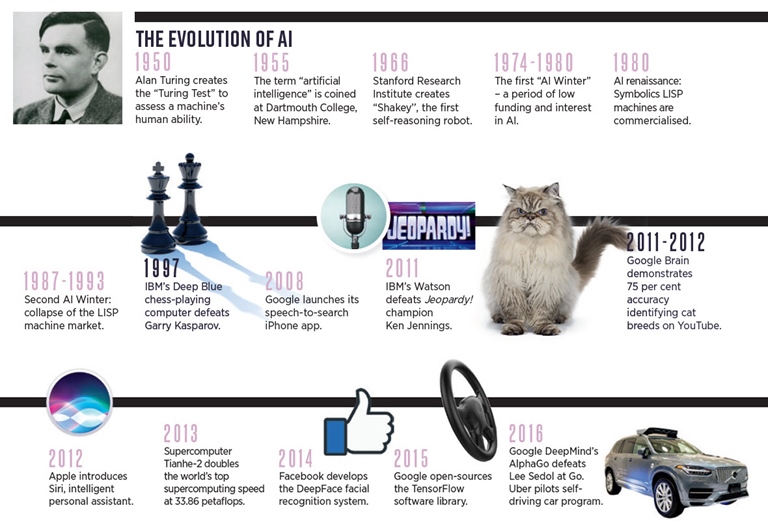

Hunter points out that the very first “killer app” was an electronic spreadsheet – VisiCalc for the Apple II, launched in 1979. He calls it “the canary in the coal mine”: it eliminated 400,000 US jobs, but created 600,000 more by making spreadsheet creation cheaper and more accessible. The result was that the accounting profession grew. He says artificial intelligence is likely to follow the same path.

Hervey says accountants have to move in a different direction “if technology is a layer over everything and everything’s been automated, and digital is everywhere and software is eating the world. The most powerful distinguishing characteristic of anyone in the accounting profession or any kind of technical firm turns out to be... what we call the human skills – your reliability, your ability to connect or empathise, or to have great conversations.”

Blockchain and audit

Hunter says blockchain technology allows a form of auditing in real time by giving organisations distributed ledgers.

“What people are really going to have to work on is the human skills based on that when so much of that kind of stuff, like entering spreadsheets, is automated. I think focusing on your ability to connect with your clients is of the utmost importance.”

Machine learning and pattern recognition

The pair says the popular concept of AI is a misnomer usually applied to machine learning, which uses algorithms and statistical models to pick out patterns and perform tasks without explicit instructions. Hervey cites a favourite quote: “If it’s written in code, it’s usually machine learning; if it’s written in PowerPoint, it’s usually artificial intelligence.”

If you’ve ever used Google’s translation service or its ability to recognise faces in photos, you’ve used a machine learning system. Machine learning has also made an impact on medicine, finance, energy management and, of course, accounting, where Xero, MYOB, Intuit and others use it to speed up the input of data, then mine it for insights.

“If you’ve got a superhuman pattern recogniser as your accounting buddy, then that’s going to be very helpful,” Hervey says. With the right software, a machine excels at pattern recognition in large datasets, in which it can spot anomalies in a fraction of the time that the same task would take a human being.

“You’re talking productivity gains of 30, 40, 50 per cent ... 360,000 hours saved by JPMorgan on their commercial loan agreements.”

New insights from machine learning

Machine learning can also be used to provide “the kinds of creative insights ... that human beings could never have even thought of”, says Hervey. This is the other direction in which machine learning research is going, pioneered mainly by the now Google-owned DeepMind.

“They’re able to say ‘we’re going to give the machine previous cases, or a huge new training set’, and the machine gives us things we weren’t even looking for,” he says.

DeepMind’s work on games of Go and chess have provided moves “that human beings have never really seen before”, teaching even grandmasters to be better players.

Hervey says this is leading to new ways of thinking about some human activities.

“That’s where I think it gets really interesting with accounting – and all kinds of other financial activity. We talk about fintech and financial investing. What kind of investment strategies are the machines able to devise once they have enough data? The kinds of investment strategies we can’t really even imagine yet.”

New technology, everywhere

Hunter, as befits his biology training, cites medical examples. “In cancer research, there’s an app on your phone called SkinVision that can diagnose melanoma at 97 per cent accuracy – whereas the best melanoma dermatologists are about 94 per cent accuracy.”

Ubenwa, a phone app developed in Nigeria, listens to infants’ cries to diagnose birth asphyxia. Hunter says this affliction is “a leading cause of infant mortality worldwide, killing 1.2 million kids each year. All you need to do is be able to diagnose it immediately ... A nurse in a maternity ward or someone in a remote village, with this free app called Ubenwa, can save potentially hundreds of thousands of infants a year.”

At the other extreme lies US spacecraft manufacturer SpaceX, which uses machine learning to solve “convex optimisation” problems as its rockets descend through the atmosphere after launching their payload.

They can then be re-used. The company can launch payloads at savings of more than 85 per cent over the Space Shuttle, thanks in part to computer code that 2019’s computers can process in real time. The basic physics of the rockets are the same as when the Saturn V sent astronauts to the moon. As Hunter notes, what has changed is the software.

Machine learning in (your) practice

Angus Hervey has been struck not only by the hype around machine learning, but also by the lack of accounting firms using it to improve their businesses. He says one reason is firms still don’t have their data in shape for machine learning to analyse it. One Future Crunch message at Congress will be that firms can start improving their data practices.

A firm that did this is among Hervey’s favourite examples: US accounting firm Garbelman Winslow CPAs, a small Maryland firm with six CPAs and 15 employees.

Garbelman Winslow partner Samantha Bowling CPA has recounted how the firm deployed software from Canadian firm MindBridge Ai in order to analyse transactions in the general ledger and classify them as high, medium or low risk.

Accountants can link their clients’ books to the platform, have it pull in information and then analyse it for transactions it flags as questionable.

Such technology can be adopted to speed up audit processes and to assess risk levels in the transactions of potential clients before taking them on.

There are no guarantees that MindBridge or any other similar software will produce economic returns for a practice. However, the price that accountants pay for experimentation has fallen: Garbelman Winslow reportedly invested below US$10,000 in MindBridge to start using the service.

Case study: how the AFP adopted artificial intelligence

“It’s difficult for police to admit we don’t know everything,” said Australian Federal Police commissioner Andrew Colvin in a late-2017 speech. “I am firm in my belief that to broaden our view, we need to get comfortable with discomfort.”

Colvin was launching the AFP’s future capability strategy, a document he says forced the organisation to lower the walls of “fortress AFP”. He said the force had started to really get a handle on its future only after it engaged with “thought leaders like those from Future Crunch”.

Angus Hervey says the AFP developed a pilot program for using machine learning to analyse 800,000 documents in a financial fraud case. Such white-collar crime is difficult to prosecute given the amount of evidence to be analysed.

Hervey says instead of using a simple but exhausting keyword search, the AFP cut the workload by training an algorithm to spot questionable transactions. It now uses AI to help review large data sets.

Tane Hunter says the FBI and AFP initially resisted using machine learning, believing it would be too difficult to implement. Future Crunch suggests a simple solution: find two promising young graduates and pay them to put it in place over six months.

“It’s about breaking down the fear, bringing people in and giving examples, not only accounting, but also for many industries, to show how everyone can be involved.”