Loading component...

At a glance

By Paul Merrill

While failure has the power to doom a seemingly unsinkable idea, intelligent failure can potentially propel a business into the stratosphere.

Thomas Edison failed 1000 times before he finally perfected his version of the incandescent light bulb.

His gruelling experimentations were nothing compared to those of vacuum cleaner pioneer Sir James Dyson, who laboured through 5126 unsuccessful attempts before finding the suction solution that made him a billionaire.

“Enjoy failure,” he once said. “You never learn from success.”

More recently, Elon Musk, the world’s second-richest person (as of April 2024), has seen his own fair share of failure, including disintegrating rockets and defective Tesla cars.

Musk agrees with Dyson about the need to get things wrong, and argues that anyone who is not failing clearly is not innovating enough.

What is intelligent failure?

Most businesses do not have the luxury of repeated disasters. Worldwide, about 90 per cent of startups fail – 10 per cent of them within the first year, according to data from Exploding Topics.

Yet some businesses do survive failure, going on to achieve significant success.

For Amy Edmondson, leadership and management professor at Harvard Business School, this happens because not all failure is created equal.

In Right Kind of Wrong: The Science of Failing Well, Edmonson distinguishes between simple carelessness or mistakes unlikely to advance knowledge, and the strategic disappointments that she classifies as intelligent failure.

“The definition of ‘intelligent failure’ is an undesirable result of a thoughtful experiment in new territory,” she says. “Without it, any organisation or project risks underperforming.”

Edmonson uses four criteria to classify failure as intelligent:

- It occurs in genuinely new territory, and prior knowledge does not exist for how to get the desired result.

- It is in pursuit of a goal, not a mere playful exercise.

- It is informed by available knowledge.

- The failure is as small as it can be while still providing the insight needed to make progress.

Upskill

The importance of calculated risk

A tactical approach to failure is becoming more critical for accountants as clients and employers increasingly expect them to play a more strategic, future-focused role.

Consequently, it has become more important than ever to encourage professionals to feel comfortable embracing failure, says business strategist Graeme Hughes, a director at Griffith University in Brisbane.

While risk aversion is an understandable attribute – especially when certainty and accuracy are prerequisites to success – avoiding it entirely can inhibit growth.

“Calculated risks are paramount as they frequently lead to growth and a competitive edge,” he says.

Hughes identifies three essential steps to foster a culture of continuous learning:

- Establish incentives for experimenting, even if it does not yield immediate success, so insights can be gleaned from both triumphs and setbacks.

- Create an atmosphere of transparency and collaboration where team members feel at ease sharing success and failure.

- Ensure there is sufficient time and resources for exploring innovative ideas, including new technologies.

Risk assessment

The degree of caution that needs to be exercised in dealing with the risk of failure is typically linked to an assessment of its potential consequences. For instance, failures that result in a loss of jobs or major damage to the company’s reputation are more serious than those that lead to a simple miscommunication or a minor missed deadline.

This means the “intelligent” component of intelligent failure requires a framework to measure what is at stake.

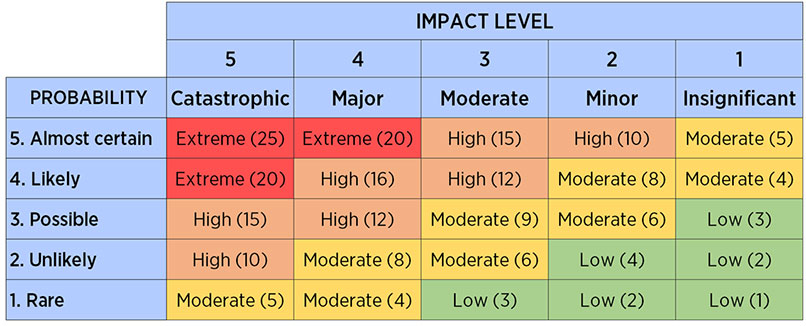

Among the most common tools used in risk management is the risk assessment matrix, a simple chart that maps the probability of an initiative going wrong on one axis and its impact on the other – see Figure 1.

Plotting risks on a chart can make it easier to prioritise defence strategies and agree on the approach to risk management.

For Edmondson, the temptation to set that tolerance too low – so that every single potential danger is minimised – presents dangers of its own. It can lead to groupthink that is averse to taking a new approach to old problems.

The approach to risk tolerance also depends on the business leadership. A skilled business leader is someone who can walk the fine line between too much and too little caution, Hughes adds.

“From the moment we wake until our heads hit the pillow at night, we engage in various risks, most of which are managed, calculated and often organised,” he says.

“Taking risks is paramount, and striking the right balance necessitates a readiness to glean insights from both triumphs and setbacks.”