Loading component...

At a glance

By Rachel Williamson

Insects have formed part of the diet of many cultures for centuries. Insects could be a viable solution for a food shortage‑fearing world, but the decade-long sprint by aspiring “bug billionaires” has yet to yield the anticipated results.

The global edible insect industry took off in the 2010s. While some start‑ups that make animal feeds containing insect protein have found success, many manufacturers of edible insect food for humans have encountered significant obstacles.

Barriers to widespread human insect consumption include the European Union’s (EU) novel food regulations, the need for new mass production practices and systems, and the shortage of up-to-date research into the health benefits and hazards of consuming insects.

The largest obstacle, however, is persuading consumers who have never looked at ants, crickets or mealworms as a food source to reconsider. Seeing insects as a source of protein rather than as household pests is a tall order.

Nutrient powerhouse

On paper, the argument for insects as human food is convincing.

Globally, more than 2100 species of insects are already consumed by two billion people across 130 countries, particularly in Asia, Africa, central and South America, Australia and New Zealand.

The protein content of edible insects, on average, is higher than in plant sources of protein, such as soybeans and lentils. The protein content of some insects, such as grasshoppers, crickets and locusts, is higher, per gram, than meat and eggs.

According to a 2021 study by Australia’s Commonwealth Scientific and Industrial Research Organisation (CSIRO) in consultation with the Insect Protein Association of Australia, “Insects have high-value nutritional profiles, and are rich in protein, omega-3 fatty acids, iron, zinc, folic acid and vitamins B12, C and E.

Commercial insect farming is considered to have a low environmental footprint, requiring minimal water, energy and land resources”.

Circular economy: what it is and how it benefits the environment

Growth potential

The EU issued its first three novel food authorisations for yellow mealworms, migratory locusts and crickets in 2021.

The 2021 CSIRO study forecasts that the insect food industry will grow to A$10 million annually over the next five years, with as many as 60 local insects that could be developed as food sources.

Grand View Research predicts the global insect food industry could grow to up to US$1.74 billion (A$2.45 billion) by 2028.

Cost and scalability

Cost is a key issue for manufacturers of insect food products for humans, because of the difficulty of manufacturing at scale.

CSIRO deputy director Professor Michelle Colgrave says that, in terms of scalability, “the black soldier fly has a lot of benefits thanks to its short lifecycle, which means you can have genetic changes occur quickly”.

“It can be self-harvested away from food sources and the scalability has already been proven,” says Colgrave, who is also professor of food and agriculture proteomics at Edith Cowan University.

"Mealworms are probably the most acceptable for human consumption, as they don’t have legs. We’ve seen people be more willing to go with mealworms over a cricket."

Black soldier fly larvae is fast and easy to grow, with about 30 products available globally today that contain black soldier flies. However, black soldier flies do not come cheap.

Bangkok-based edible insect expert Massimo Reverberi, founder of cricket pasta company Bugsolutely, says that if fish meal costs US$2-$4 (A$3-$6) per tonne, black soldier fly powder is double that.

“Cricket flour is down to maybe US$20-$30 (A$30-$45) per kilo in the US and in Europe, but there are only a few farms and few companies processing the product into flour,” Reverberi says.

“We need to learn how to farm all these insects in an optimal way,” Reverberi says. “We have only been doing it a few years, compared to decades of factory farming animals.”

All in the packaging?

Reverberi highlights the disconnect between traditions of eating insects and packaged food like protein bars and flour. “People who traditionally eat insects eat them freshly fried.

They are not a processed product. This is a really old farm tradition that has nothing to do with the supermarket in a city.

“Over the last decade or so of excitement and media attention on insect start-ups, people connected two things that are, in my opinion, disconnected,” Reverberi says.

Many insect food start-ups zeroed in on energy bars, he says. “The reasoning is that insects contain a lot of protein, so the fastest way to mainstream consumers is to target the fitness market.

“They tried to sell this new, strange product online, but the energy bars segment is so packed they couldn’t cut through, so they never got visibility.”

The ick factor

Perhaps the most significant issue is the matter of taste – what consumers assume insects taste like.

While some consumers in the West may view insects as disgusting, Reverberi, a true insect connoisseur, ranks crickets as the most delicious, then mealworms. Mealworms, he says, are similar in flavour to chestnuts.

Some insects are not suited to human taste buds. Black soldier flies are bitter, so they are currently only used in animal feed and pet food despite being the quickest and easiest insects to grow.

It is unclear whether edible insects meet the requirements for some diets at all, such as whether they are kosher or halal.

CSIRO deputy director Professor Michelle Colgrave recommends starting with the so-called low-hanging fruit to overcome the “ick” factor.

“Mealworms are probably the most acceptable for human consumption, as they don’t have legs. We’ve seen people be more willing to go with mealworms over a cricket,” says Colgrave.

Animal feed opportunity

CSIRO and Insect Protein Association of Australia research into insect food offers a possible blueprint for Australia to build an animal and human food export industry.

Colgrave says that edible insects as animal feed and pet food is the most likely consumer adoption pathway, where there is the greatest opportunity for production at scale.

Europe is the hub for global insect production, led by Netherlands-based chicken, aquaculture and pet food giant Protix. French company Ÿnsect is driving the movement towards greater acceptance of insects in human food and was instrumental in the novel food authorisation of mealworms in 2021.

"We need to learn how to farm all these insects in an optimal way. We have only been doing it a few years, compared to decades of factory farming animals."

InnovaFeed, another a French company, is a big European player, using black soldier flies to create protein powder, oil and fertiliser.

In Australia, PetGood, Buggy Bix and Feed for Thought make insect-based dog foods, while Bardee, FlyFarm and Future Green Solutions make fertiliser and supply protein for pet and animal foods.

Insects may make up a small portion of products for humans in the coming decades, but today, the growth is in animal feeds. More research, more time and, crucially, more money needs to go into the industry before it can begin to meet the stretch goals aspired to by researchers and budding insect food start-ups.

Links to known allergens

The insect food protein extravaganza comes with a hidden sting – allergens.

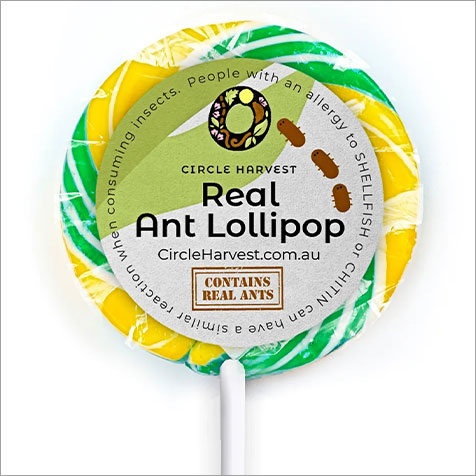

Shellfish are a major food allergen for humans, affecting about 2 per cent of people in the US, for example. As crustaceans, insects are close cousins of shellfish. A 2021 study led by Colgrave found 20 allergenic proteins in crickets that are also found in crustaceans.

“We consider it a cross-reactivity – where you are allergic to prawns and cross-species can trigger that allergy. We are sequencing the proteins of crickets, mealworms and black soldier flies and comparing them with all known allergens,” Colgrave says.

“It’s about making sure consumers have awareness and food manufacturers label things appropriately. It’s really important that we understand the potential implications for food safety and identify the new and novel bioactive components that can improve our health, such as lower cholesterol or improve cardiovascular health.”

Nuisance to nutrition

Phoebe Gardner, CEO and co-founder of Bardee, Australia’s largest black soldier fly breeding, fertiliser and protein company, says prices for its feed products have increased by 60-100 per cent since the company launched its first product in late 2021.

“The price of proteins and meals have increased dramatically over the last two years with disruption to supply chains, COVID-19 and political tensions,” Gardner says.

“The demand for our protein supply is for dog food, from small ecommerce brands to supermarkets. We also work closely with large pet food makers like Mars Petcare. Those first companies – Buggy Business, Grubbo and others – were building pet food brands around insect ingredients, and we were and still are the only supplier in Australia who can fulfil their orders.”

Bardee generates carbon credits because it redirects food waste from landfills for insect feed. This takes up little space compared to animal or plant farming, uses far less water and has lower greenhouse gas emissions.

Every tonne of human food waste Bardee diverts from landfill creates 1.9 tonnes of carbon offset. Bardee produces up to 40 tonnes of protein a month from black soldier fly larvae at its commercial plant in Victoria. The company also plans to build a 70-tonne-a-day protein plant.

“We are able to get a 3000 times growth rate in seven days – the fastest in the world by about 50 per cent. Our insects are 15 per cent protein when we harvest them, which is significantly higher than in nature, where they might be 9 per cent.

"The harvest is a frozen mince and a flour that are 60 per cent protein. The value is that it can replace soy, fish and meat meals, which are unsustainable,” she says.

Gardner is keen on expanding into the human foods industry. However, black soldier flies are native to Florida, so they are not approved for consumption in Australia, “unlike local insects such as bogong moths, witchetty grubs or honeypot ants, which are classed as non-traditional foods because they have long been part of Indigenous diets”.