Loading component...

At a glance

Behavioural ethics can provide some interesting insights into our views of ourselves and also the effects that conflicts of interest can have on our behaviour.

And although we tend to think that we can remain objective and guard against the influence of conflicts of interest, there is now sufficient research that shows our human limitations when faced with conflicts.

In the medical profession, while most doctors think they are invulnerable to influences from pharmaceutical companies, research shows often their beliefs about medications reflect the advertisements and literature of the companies rather than the medical research.

Other research shows that while 61 per cent of doctors thought they were not affected by the pharmaceutical industry’s “freebies”, only 16 per cent thought other doctors would be able to resist.

Similarly, in another study, many medical students thought gifts a problem in other professions, but not in medicine.

Overall, we are likely to accept that others are or can be affected by conflicts of interest and be biased as a result, but refuse to accept that we also may be affected. We tend to have a stubborn view of ourselves as more ethical, competent and objective than others.

A conflict of interest is a conflict between our professional responsibility to protect the interests of our clients, profession and the public, and our own interests.

A conflict of interest compromises our judgement/objectivity and is not only a consequence of material or economic interests – personal relationships, familiarity and affiliations also create conflicts.

Succumbing to a conflict of interest may be due to corrupt and unethical intention, or it may be unconscious or unintentional. The latter is more common. So, good people like us can and are affected.

There is ample evidence that shows we are able to recognise how conflicts of interest may lead to biased decisions, but only in others, not ourselves.

This overconfidence in our ability to remain unbiased, upright and ethical poses a big threat to our professional judgements.

Research has found that accountants can be influenced by financial relationships with their clients due to unconscious biases that affect how information is perceived and processed.

Generally, the way we search for and use information is affected by our goals and pre-existing views. Unconsciously, we may not see information we should be paying attention to.

We are also more likely to uncritically accept information that supports our view and are more likely to reject information that opposes our views, or at the very least, be a lot more critical towards it.

Unconscious and unintentional biases have been called mental contaminations, which unlike physical contaminations, can be very problematic – there are no physical signs, so they can be extremely hard to detect.

Conflicts of interest arise in all professions and a dangerous response is to think that we are so ethical and strong that conflicts of interest are not an issue for us – but they are for everyone else.

Such a response leads to the inability to recognise conflicts for what they are and what they can do to our judgement, creating ethical blind spots. We need to keep in mind that we think:

- we are unbiased

- we can make sound, rational decisions

- we are objective and fair

- we are more ethical than others

So what should accountants do?

The best remedy is to avoid conflicts of interest altogether but this is not always possible.

We need to focus on identifying and defining conflicts of interest, actual or potential, from our view and from the view of different groups.

When we identify a conflict of interest, our default should be to expect that it will cloud our judgement, rather than think that we’ll remain uninfluenced and objective.

It is better to believe: “I will not be able to resist the effects of an interest” rather than be unconsciously biased.

Remember, there is no bad smell that will alert us to the existence of unconscious bias, so we need to be vigilant about the effect of our relationships and interests on our judgement, our objectivity and our integrity.

We need to go past the initial response that conflicts are something other accountants should worry about, but not us.

We need to accept that if the threat of self-interest is present, our judgements will be biased.

We need to remember that what we see and how we see it may subconsciously be coloured by our self-interest.

We should remember that many unethical and illegal actions are not a consequence of the motivation to do the wrong thing, but a consequence of unconscious bias.

If we suspect a conflict of interest we should consult colleagues who do not share our direct interests, relationships and experiences – but of course in doing so we also need to consider our confidentiality obligations.

We should accept that we are vulnerable and be aware of our human limitations.

APES 110 Code of ethics for professional accountants

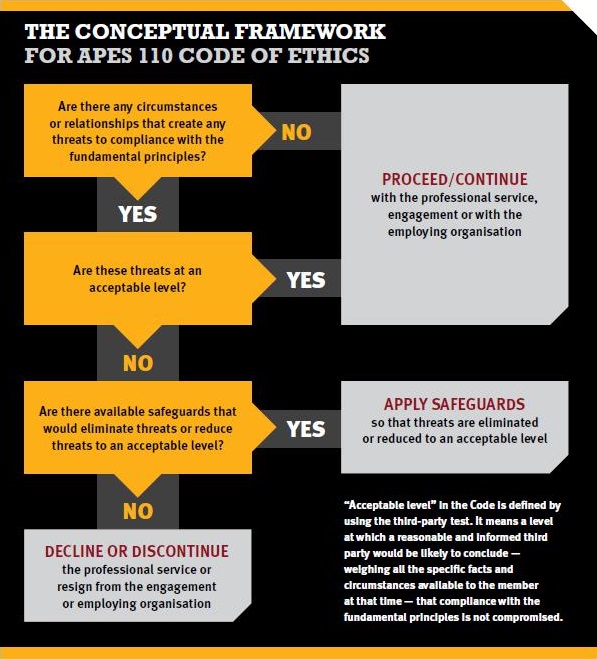

The Code provides a framework that members of CPA Australia must use to identify, evaluate and address any threats to compliance with the fundamental principles of integrity, objectivity, professional competence and due care, confidentiality and professional behaviour. It relies on active consideration of issues and on professional judgement.

Threats to our principles may be created by a number of circumstances or relationships and may fall into one or more of the following:

- Self-interest threat: the threat that a financial or other interest will inappropriately influence a member’s judgement or behaviour.

- Advocacy threat: the threat that a member will promote a client’s or employer’s position to the point that the member’s objectivity is compromised.

- Self-review threat: the threat that a member will not appropriately evaluate the results of a previous judgement made or service performed by the member, or by another individual within the member‘s firm or employing organisation, on which the member will rely when forming a judgement as part of providing a service.

- Familiarity threat: the threat that due to a long or close relationship with a client or employer, a member will be too sympathetic to their interests or too accepting of their work.

- Intimidation threat: the threat that a member will be deterred from acting objectively because of actual or perceived pressures, including attempts to exercise undue influence over the member.