Loading component...

At a glance

By Rachel Williamson

Australia’s energy system is being squeezed between new and old technologies after a decade-long planning vacuum. However, with a little over six years left to achieve the 2030 Breakthroughs of the Paris Agreement, modernising the country’s electricity is now a matter of urgency.

Australia’s preferred new technologies, wind and solar, are putting pressure on a grid that was never built to transport intermittent energy generated from many dispersed locations. Bringing it up to speed will cost a minimum of A$12.7 billion, says the Australian Energy Market Operator (AEMO).

At the same time, ageing gas and coal power plants are exposed to international market prices for their fuels, which surged following the outbreak of war in Ukraine.

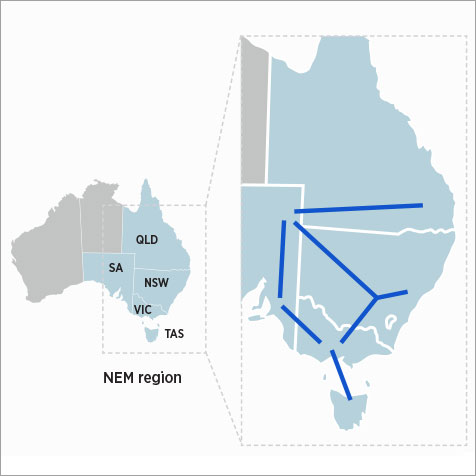

Crisis followed in June 2022 as coal power plant owners shut down their assets, citing high fuel prices. This likely would have collapsed the National Electricity Market (NEM) – made up of Queensland, New South Wales (including the ACT), Victoria, Tasmania and South Australia – if AEMO had not assumed temporary control.

In November 2022, the Australian Treasury assumed energy prices would rise by 20 per cent year-on-year by the end of 2022 and 30 per cent in 2023.

This means that the next six years will be tumultuous as Australia chases the Paris Agreement’s 2030 Breakthroughs via a patchwork of reforms led by the states, before energy prices and the system itself begin to smooth out.

Dr Alan Finkel AC, chair of the Technology Investment Advisory Council and former chief scientist, says the electricity system needs to be robust.

“It needs to be reliable and secure, so we cannot be simplistic about this – there is no simple way forward. We have already denied ourselves other sources of renewable energy such as nuclear or hydropower.”

“We have committed to using solar and wind as our primary energy, and they are electrically very difficult, and we have to supplement them to make the system robust,” Finkel says.

Net zero mandate

After winning the 2022 election, Australia’s Labor government launched its first term with a series of energy policies. The main pushes, however, are 82 per cent renewables by 2030 and the A$20 billion Rewiring the Nation energy grid upgrade package, which is part of the larger Powering Australia policy.

Meanwhile, the states are playing catch-up. Victoria is targeting a massive 2.6 gigawatts (GW) of storage capacity installed by 2030, with 65 per cent of its power to come from renewables by 2030, and 95 per cent by 2035.

In New South Wales, the target is 12GW of renewables and 2GW of long duration storage by 2030. Queensland’s target is 70 per cent renewable energy penetration by 2032. South Australia has already got there – it was renewables-only on 180 days into 2021.

Western Australia has promised to close its last two state-owned coal power stations and is backing a suite of proposals, from a 1GW big battery near the coal town of Collie, to a possible 11.5GW of offshore wind farms.

"There will be costs whether you return to fossil fuel power, which is expensive to install new and relies on trade-exposed fuel, or continue to install renewables, which requires new long-duration energy storage and grid upgrades."

Benchmarking these goals against global strategies gives a mixed picture. Australia was one of the few countries to take a higher emissions reduction goal – 43 per cent by 2030 – to COP27 in Egypt, but that was from an unambitious base.

Carl Tidemann, Climate Council senior researcher, says, “With benchmarks specific to electricity markets, we are doing quite well because that has been the main focus for quite some time, which started with the Mandatory Renewable Energy Target in 2001.

“If you look more broadly at other sectors, we are not doing as well. There has been so much focus on power that most of the other sectors have been neglected.”

According to Tidemann, Australia has not made much progress along International Energy Agency’s net zero road map, which highlights targets that must be achieved to reach net zero by 2050.

Analysing new Australian climate policies

Cost of inertia

Among the costs of inaction are high prices and a hefty bill for supporting the transition that is already under way, Tidemann says.

“There will be costs whether you return to fossil fuel power, which is expensive to install new and relies on trade-exposed fuel, or continue to install renewables, which require new, long-duration energy storage and grid upgrades,” he says.

“However, replacing fossil fuel generators like for like would be far more expensive than renewables and storage, not to mention the ongoing emissions.”

The cost of doing nothing also runs the risk of adding billions in export tariffs if regions such as the European Union enforce carbon border adjustment mechanisms – effectively a tax on emissions-intensive products.

Transmission conundrum

While government targets are creating optimism, the question of whether the grid infrastructure can support them remains.

Grid projects take years in planning and construction. While many are in progress, keeping to budget and timelines can be difficult.

For example, the Marinus Link, a 1500MW Tasmania–Victoria undersea electricity and telecommunications connection designed to allow electricity in both directions, will enable more mainland wind and solar to launch by connecting to Tasmania’s enormous pumped hydro storage capacity.

However, the project will not be finished until 2031, falling short of the Australian Government’s target of 82 per cent renewables by 2030.

Infrastructure expert Tim Buckley, director of Climate Energy Finance, says the project will cause “inordinate levels of dislocation”.

“Transmission is a known quantity, but Australia has not done a lot of interstate grid construction,” Buckley adds.

“You need strong social licences to operate these, because they are complex engineering projects that require special cables, are of phenomenal size, and involve land acquisition.”

Strategy disconnect

Without a unified approach, fragmentation of rule requirements may occur as the states take matters into their own hands.

Victoria has revived the State Electricity Commission Victoria to deliver government‑owned renewable energy, create jobs and, according to Premier Dan Andrews, “drive down power bills and put electricity back in the hands of Victorians”.

Queensland is consolidating state ownership of power infrastructure to keep jobs in the state, pledging to repurpose its coal power stations into clean energy hubs.

New South Wales has pledged to create five Renewable Energy Zones (REZs) that provide renewable energy infrastructure, storage and transmission infrastructure to encourage investment in renewable energy projects, cut power bills and reduce emissions.

Infrastructure gaps

The biggest challenge to achieving the 2030 Breakthroughs is infrastructure connection. While Australia’s interconnected grid, the NEM, is one of the longest in the world, the power it generates is dwarfed by the world’s largest interconnected grids.

For instance, while Australia’s NEM generates about 200 terawatt‑hours (TWh) of power annually, the North American interconnected grid generates about 4200TWh. During December 2022 alone, Mainland China produced 757.9TWh of electricity.

"The electricity system needs to be robust. It needs to be reliable and secure, so we cannot be simplistic about this – there is no simple way forward. We have already denied ourselves other sources of renewable energy such as nuclear or hydropower."

This raises the question of whether Australia’s NEM will be able to cope with increased output, especially in areas of the grid not built to handle bulk energy transmission.

The NEM’s open access regime means there is no queuing, and everyone is entitled to be connected. The upshot is that AEMO cannot unilaterally progress one project and move on to the next – it must consider all generation projects simultaneously.

Future of energy

The future will involve long duration storage for “firming” or grid stability. This could be in the form of pumped hydro and big batteries, but also possibly newer technologies such as gravity and compressed air batteries, or solar thermal.

In December 2022, the Australian National Cabinet energy ministers’ meeting agreed to launch a mechanism to support long duration storage and big batteries.

To date, these have relied largely on grid stabilisation payments for revenue and selling energy into the open market – neither of which are certain enough to convince investors to fund high upfront capital costs.

Another question is around the kind of rules that will be needed to guide the increasingly sophisticated market.

AEMO has shifted away from imposing locational marginal pricing, a short-term price signal that reflects the value of energy at a single time and place – a measure of quantity and ability to get it from generator to end user, in Australia’s case.

However, this does not help to guide long-term planning on where new investment should go. AEMO is now considering a congestion charge for parts of the grid where there are many projects.

It is also working on dynamic operating envelopes, or areas where instead of blanket restrictions on how much electricity a rooftop or farm can sell into the grid, the limits rise and fall depending on how much power is being sent into the grid and taken out at any time of the day.

The rules must also encompass rooftop solar – which contributed just under 10 per cent of power in the NEM in 2022 – as well as household and vehicle batteries.

In the US, the new Ford F-150 utility vehicle does two-directional charging and promises to be powerful enough to power a home at a rate of 9.6kW for three days, but there are no regulations in place to allow this in Australia for now.

“By 2030, we will have 20 million batteries on wheels in this country – maybe 1000GW of battery capacity or 10 to 20 times the grid capacity of the whole market today,” Buckley says.

“Imagine if only a quarter of that was connected to the grid. We need regulatory processes and pricing structures for that.”