Loading component...

At a glance

- Moves to change a country’s capital city are not uncommon, and Indonesia is the latest country to set out a plan to move its capital city.

- Heavy traffic congestion is a common reason for moving a capital city. Another rationale is the potential to redistribute national wealth.

- Economists argue that recent, unsuccessful moves of capital cities indicate Indonesia would be better off focusing on improving its existing infrastructure.

Herwan Ng FCPA lives 10km from his office at Freeport Indonesia in Jakarta, where he works as a part-time consultant. During rush hour, the journey takes at least 45 minutes because he shares the snarling roads with 3.5 million commuters. Ng also has regular meetings at AWR Lloyd and Grant Thornton, where he serves as a senior adviser, and makes frequent trips around the city for his other roles as independent commissioner and audit committee member.

The hours Ng wastes each week in what has been described as the world’s worst traffic are a frequent source of frustration, so it is unsurprising that he supports a new plan to move Indonesia’s capital city.

“I think it’s a positive idea, if it can really happen. The current situation isn’t conducive to business,” he says.

Ng says Jakarta’s traffic problems are an obstacle to his country becoming a developed, high-income nation because they deter foreign investors and international event organisers.

However, traffic is not Jakarta’s only problem. The heaving megacity of 10 million is sinking at one of the fastest rates in the world: by 2050, 95 per cent of the northern part could be under water as a result of groundwater drilling and the sheer weight of its skyscrapers. The negative effects of Jakarta’s traffic congestion and pollution are thought to cost the economy US$10 billion annually.

The ambitious lan to start afresh with a new capital was announced by President Joko Widodo shortly after he declared victory in the general elections in April this year. He isn’t the first leader to propose the idea, but this time around it appears to be really happening.

National Development Planning Minister Bambang Brodjonegoro told The Jakarta Post in June that the plan to move the capital was “final” and that it would be completed within five years – that is, within Widodo’s second and final term in office.

Some say the precedent set by other newly created capital cities around the world suggests that Indonesia should keep its capital where it is, and instead focus on improving existing infrastructure.

“The fact that there haven’t been successful moves of capital cities in recent times suggests that even with all the technology we have to overcome geographical distance, it remains more difficult than ever to move a city,” says Jarrod Ball, chief economist of the Committee for Economic Development of Australia (CEDA).

He says Egypt’s new capital is a case in point. In 2015 the government cited Cairo’s heavy congestion as the reason for shifting the capital to an undeveloped area 40km away. Costs were unclear from the outset and are expected to keep climbing from the current price tag of US$58 billion.

Some investors have already deserted the project. Like Indonesia, Egypt is a developing country with limited means to finance such a move.

Marcus Lee, senior urban economist at the World Bank in Indonesia, says that if Indonesia were to move its capital, there’s scope for finance to be provided for basic infrastructure. He declined to say whether the World Bank supports the move, claiming the issue is politically sensitive.

Lee cites the example of the new state capital of Andhra Pradesh in India, where the cash-strapped government is likely to receive a US$200 million World Bank loan to build a centralised sewerage network. However, the reasons for building a new capital there are very different: the state lost its capital city of Hyderabad when the borders were redrawn in 2014. The price tag for building Amaravati, which is being billed as one of the world’s most sustainable cities, is much lower, at US$6.5 billion.

"Jakarta is the engine of Indonesia and there is great disparity between the rural and urban populations. Moving the capital would even out the social polarisation and support more balanced regional development."

“The idea behind the World Bank project in the new city of Amaravati is to finance some important basic infrastructure, which the government may not invest in without our support,” says Lee.

He says only 2 per cent of Indonesia’s urban population is served by a centralised sewerage network and that the World Bank would consider funding sewerage projects both in Jakarta and a new capital city.

Does moving capital cities achieve a fairer distribution of wealth?

Vadim Rossman, a professor at the Higher School of Economics in St Petersburg, says the soundest strategic reason for moving a capital city is to redistribute national wealth.

“[A capital city] holds much of the country’s population, as well as its resources. That creates an unequal relationship between the capital and the provinces. A goal of placing the seat of government elsewhere is to achieve more equal access to the public goods associated with capital cities,” he says.

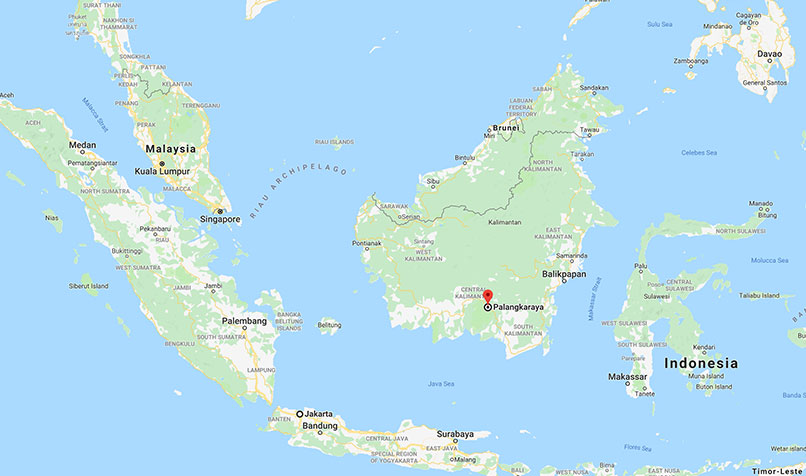

Inequality is undoubtedly an issue for Indonesia. It is made up of 18,000 islands, but more than half of the country’s population of 260 million live on the island of Java, where Jakarta is located. Wealth has historically been concentrated there too, despite the natural resource riches of its outer regions. The likely new capital is Palangkaraya, 1000km from Jakarta on the island of Borneo.

The Indonesian Government has said the decision to create a new capital is “a symbolic move to address the imbalances in regional development”.

Associate Professor Hoon Han, director of the city planning program and a co-convenor at the University of New South Wales, agrees with the rationale for the move.

“Jakarta is the engine of Indonesia and there is great disparity between the rural and urban populations. Moving the capital would even out the social polarisation and support more balanced regional development.”

However, Lee says the evidence doesn’t back this up.

“We have looked at the lessons learned from other countries where a new capital city has been built away from the current capital and larger cities.”

He cites Malaysia’s Putrajaya, the federal administrative centre 25 km south of the capital Kuala Lumpur, Canberra in Australia and Sejong City in South Korea.

“In all these cases, it has been ineffective as a way to rebalance the population and basic economic activity,” Lee says, “and it isn’t a good strategy if you are intending to solve overcrowding in existing cities.”

Playing the long game when moving capital cities

Lee says that there can be benefits to moving a capital city – but it can take at least 50 years to realise them.

“The economic vibrancy of existing cities isn’t easy to create overnight. The private sector won’t automatically move just because the national government moves its offices,” he says.

The administrative capital of South Korea, Sejong, is an example. Some government offices moved there in 2012 and high-speed rail connects it to Seoul, 112km away.

“Many government offices are there, but no one’s really relocated,” says Lee. “Civil servants commute weekly and their families and social life have remained in Seoul. Sejong is a rather soulless city.”

University of Melbourne urban politics and planning expert Professor Michele Acuto says Australia’s economic powers remain separated from the seat of political power more than a century after the creation of Canberra.

“Australia’s economic power still resides with Sydney and Melbourne, so you don’t have that direct proximity,” he says.

“Canberra has been successful to a degree, and it has put in place more community initiatives, but there remain questions. Furthermore, there’s almost a century of difference between it and the current situation in Indonesia, so the parallel doesn’t hold.”

Lee says the most successful example of a new capital city is Brasilia in Brazil, which replaced Rio de Janeiro as the administrative capital in 1960. Today it has the highest GDP per capita of any major Latin American city and a population of three million.

“A new capital city can create a powerful national symbol over the long term. It can also reduce some of the rivalries in different regions. This was the case with Brasilia, which moved the federal government closer to the geographical centre of the country,” Lee says.

Similarly, the Russian historian Nikolay Karamzin famously described St Petersburg as a “brilliant mistake” because it took generations for it to flourish. What was once a depressing place to work in is now known as the “Venice of the North”, and has played a critical role in the formation of Russian identity.

Acuto questions whether you can speed up that process in modern times.

“You may have the ability to deploy infrastructure much faster using new technology, but how are you going to move the people? It’s the people that are the critical ingredient to a successful city.”

The smart enough city

When governments announce the creation of a new capital city, they almost always promise it will be a “smart city” that incorporates technology to improve urban services. Indonesia is no exception. However, author Ben Green says in The Smart Enough City that the term denotes a futuristic urban utopia where technology solves every problem.

He argues that technology is not an end in itself, and that some cities appear smart, but are rife with inequalities. He calls for cities to be “smart enough” – to embrace technology as a powerful tool when used in conjunction with other forms of social change – but that people must always be put first.