Loading component...

At a glance

- Economists and policymakers expect a long-reaching impact from widespread job losses in industries that are female-dominated.

- Addressing unemployment and devising strategies for lowering underemployment are also necessary.

- Economists emphasise the need for initiatives specifically targeted at boosting female labour force participation.

After a long period of economic stability, Australia took a backward slide in 2020, following the horror summer of bushfires and the COVID-19 pandemic, officially entering its first recession in three decades.

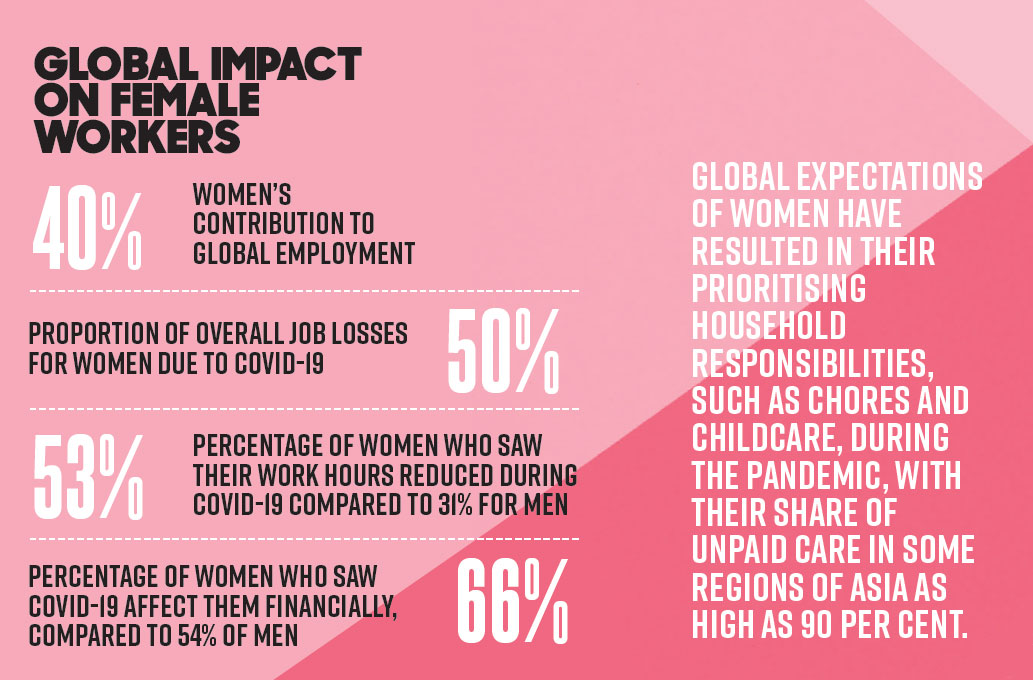

What marks this recession as different from previous ones is the toll it has taken on women’s participation in employment and their prospects for a financially secure future.

How the economy will recover from the pandemic is uncertain and, with the federal government budget stimulus measures focused on mostly male-dominated industries such as construction and energy, questions have arisen about whether there are alternative measures to drive economic growth and benefit for all Australians.

Colour coding a recession

As workforce data emerged in the first few months of the pandemic, experts started referring to its impact on women’s employment as a “pink recession”.

It became clear that women bore the brunt of the rapid closure of many businesses across female-dominated industries such as hospitality, tourism, retail, aged care and childcare.

Data from the ABS Weekly Payroll Jobs and Wages early in the pandemic showed an overall drop of 7.5 per cent for jobs between mid-March and mid-April, with losses across all industries. However, the number of jobs slumped by a steeper 8.1 per cent for women, compared with a drop of 6.2 per cent for men.

While more recent figures from the ABS have shown job losses for men have outpaced those for women, female-dominated industries remain significantly affected by the economic downturn.

Rae Cooper, professor of gender, work and employment relations at the University of Sydney Business School, says Australia’s workforce is highly gendered, and that COVID-19 is likely to have a long-reaching impact on sectors in which female workers dominate.

“I think we’re going to see a very long-term impact on those sectors that have seen high job losses. I don’t think we can assume that they’re going to bounce back straight away,” says Cooper.

“Unemployment is a really critical issue to think about, but we also need to look at underemployment – which is at an all-time high for women who would like to work more hours.”

Despite the evidence of significant job losses for women, the Australian federal budget heavily focuses on stimulus spending in male-dominated industries, allocating a combined A$27 billion across areas such as construction, energy, transport and manufacturing.

In comparison, just A$240 million has been allocated to increasing women’s workforce participation, through a range of initiatives such as closing the gender pay gap, getting more women into STEM (science, technology, engineering and mathematics) positions and lifting the numbers of women in construction, leadership and entrepreneurship.

According to a team of 36 subject matter specialists with National Foundation for Australian Women (NFAW), “the budget is a lost opportunity to maximise employment growth, to invest in social infrastructure with the greatest multiplier effects and to address the structural problems in female-dominated areas that COVID-19 has exposed”.

Professor Helen Hodgson, Curtin University academic and chair of NFAW’s social policy committee, says not taking a gender-focused approach to economic recovery reduces the capacity to drive growth across all industries.

“One of the sections that we always look at carefully is around the way that the government makes decisions. And, essentially, what we’re saying is, you need to have women at the table when these decisions are being made to understand whether a particular proposal is going to have the same effect on women as it does on men,” Hodgson says.

Matt Grudnoff, senior economist at the Australia Institute, says this recession differs from previous ones due to the increase in insecure and casualised work in industries dominated by women. He says any recovery effort has to also include specific initiatives to support female labour participation.

“In previous recessions, the biggest impact on unemployment was on older working males – men lost jobs faster than women,” says Grudnoff. “The labour market has since changed, and we’ve seen the introduction of casualised or insecure work, and that has generally seen more women taking on those roles – and they are the jobs that have been most impacted by the pandemic.”

Ruth Medd FCPA, chair of Women on Boards, says the infrastructure and tax cut measures in the budget have overlooked the pandemic’s impact compared to previous recessions.

“There is a growing movement around the need for a care-led recovery. The key driver for economic growth in Australia is increasing female participation rates in the workforce, and one of the ways of doing that is to enable women who’ve got school or childcare-aged children to work more than three days a week.”

Building towards recovery

Grudnoff points out that the areas for stimulus spending targeted in the Australian Federal Budget mirror previous recovery efforts during recessions and do not necessarily address the current unemployment rates.

“Historically, the focus on stimulus projects has definitely been about construction and infrastructure, which are male-dominated industries.

“But that’s not where the jobs have been lost, and so we need to rethink that spending.”

In terms of actual job creation, Grudnoff argues the benefit lies in boosting sectors with higher employment opportunities.

“As economists, we look at how many jobs every additional million dollars of spending you put into an industry would create.

“In construction, it’s 1.2 jobs. If you put that spending into childcare, for example, it would create about 20 jobs,” he says.

Independent analysis by the Centre of Policy Studies, commissioned by NFAW, provides a scenario where government investment in the care sector (including aged care, childcare and disability) could generate higher levels of activity in the economy.

According to NFAW, more than 900,000 Australians who currently provide unpaid care to the elderly, disabled or children aged under five report that they would like to work more hours in paid employment.

Providing the additional funding needed to enable them to work an extra 10 hours a week in paid employment would improve quality of care, create more jobs for women and grow the economy through increased participation, says Hodgson.

“The modelling that we commissioned looked at what would happen if we increased wages in the care sector, then increased the amount of care available to boost workforce participation.

“The results show that labour supply would be over 2 per cent higher, and the modelling estimates that annual GDP per person would be A$1266 higher, or more than A$30 billion a year.”

CPA Library resource:

Economies of childcare reform

There is a long-running argument that more accessible and affordable high-quality childcare would have a significant positive impact on labour force participation rates.

“Government funding of childcare should not be seen as a welfare policy, but instead as economic reform. Providing affordable to free high-quality childcare to all people actually benefits our economy by increasing workforce participation rates,” Grudnoff says.

Grudnoff’s research paper, Participating in Growth: Free Childcare and Increased Participation, looks at participation rates in Australia versus Nordic countries. The findings show that Australia’s female work participation rates fall significantly at the ages when the largest number of people are raising young families and never return to peak levels.

“If Australia had the same labour force participation rates as Nordic countries do, then the economy would be A$60 billion – or 3.2 per cent of GDP – larger,” says Grudnoff.

“If Australia had the same participation rates as Iceland, the Nordic country with the highest female participation rates, then Australia’s GDP would be A$140 billion – or 7.5 per cent – higher.”

Cooper says reforming Australia’s childcare sector would not only improve the quality of care, but it would make it easier for both men and women to access the labour force.

“There’s a lot of evidence to suggest that if we increase professional wages and build professional training into early childhood education, then the outcomes for children are a lot better,” she says.

“The sector is very complex to navigate – and it’s really expensive in Australia. We need more places available, we need better quality childcare and we need the cost to be affordable for families.”

Medd points out that, while the way out of the pandemic is still being navigated, the most equitable recovery efforts need to reflect the changed nature of the workforce and the impact the pandemic has had on women.

“I think a lot of people agree there needs to be a different type of recovery out of COVID than there was out of the GFC.”