Loading component...

At a glance

To begin to understand Israel’s remarkable rise as a magnet for technology start-ups, it is worth listening to serial entrepreneur Eynat Guez.

“In Israel, you execute first. You say ‘I can deliver this’ and you think about how to do it afterwards,” says the founder of Papaya Global, a Tel Aviv business that automates international companies’ workforce and payroll management.

Guez is one of a large cohort of intelligent, ambitious business people in Israel who are cementing the small Middle Eastern country’s status as a serious rival to other technology and venture capital ecosystems such as California’s Silicon Valley, Shanghai and London.

Just don’t expect the focus in Israel to be on carefully executed business plans. The Israeli emphasis is on ideas, speed and rollout.

If that means the innovations are slightly unformed, so be it. If that means some entrepreneurs crash and burn, no problem.

“You can say it proudly,” Guez says. “Failing in a venture in Israel is not something you try to hide. It’s part of your growth.”

Eighteen months after its launch, Papaya Global has plenty of customers on its books, but it’s now finalising a Series A round of financing (the first significant round of venture capital funding) to help its workforce management platforms become a big international hit.

It's the latest venture for Guez, who says start-ups in Israel are willing to take “very big risks”.

“They will not spend their time on risk management – only the really necessary things that they need to do,” she explains.

A start-up formula made in Israel

The formula is working for Israel. Despite having a population of just 8.5 million people and once being better known as the home of the kibbutz, the nation has developed more high-tech start-ups than all of Europe in recent years, and trails only the US on that score.

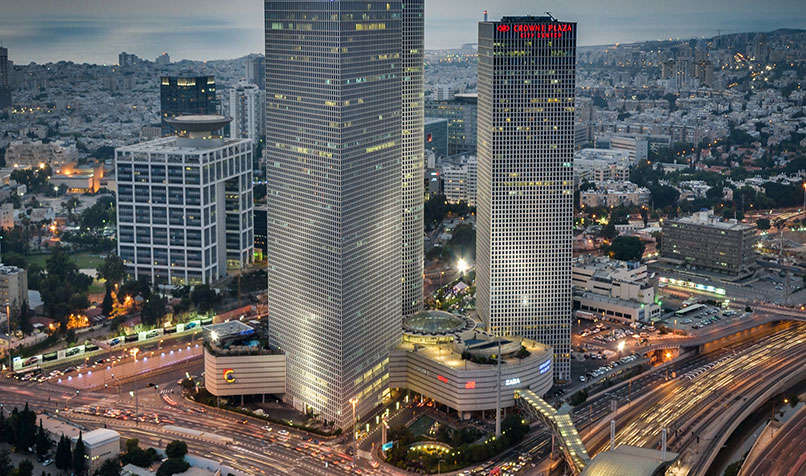

Silicon Wadi (wadi means valley in Arabic) is an area around Tel Aviv on the country’s coastal plain that has a cluster of high-tech industries built around military, start-up and venture-capital communities.

Dun and Bradstreet counted 4750 high-tech start-ups in Israel in 2016, and those start-ups are clearly on the radar of the world’s tech giants.

In March 2017, Intel bought Mobileye, a leader in computer vision for driverless car technology, and paid US$15.3 billion, the biggest high-tech deal in Israeli history.

Companies such as IBM, Google, Facebook, HP and Oracle have a presence in the region and are using their ties with Silicon Wadi enterprises to enhance their innovation, and research and development strategies.

Rising stars of the digital world are also taking their cues from Israel.

Tim Fung, co-founder of Australian mobile marketplace Airtasker, visited Israel a couple of years ago on an Investec Global Entrepreneurs Trip, organised by Investec and the South Africa-Israel Forum.

He was impressed by the ambition of his Israeli counterparts, and the integration of the military and technology sectors.

“People in Israel really support each other’s companies,” he says.

“They believe they can make it, and talk about success a lot. This is a super-important factor and I think something that we Aussies can improve on.”

Fung adds that Israel has the chutzpah of superpowers such as the US and China and knows it must pursue international business products and services.

“It is very much focused on solving global problems rather than local ones.”

Learning from Israel's Silicon Wadi

Silicon Wadi is no overnight success. Tax cuts in the mid-1980s kickstarted a stagnant national economy, and the software boom of the 1980s and 1990s aided Israel’s emergence as a technology innovator.

Yozma, a government initiative, effectively created Israel’s venture-capital sector through a scheme that offered tax incentives to investors and entrepreneurs.

Catherine de Fontenay, an associate professor of economics at the Melbourne Business School, is not surprised by Israel’s standing as a high-tech power.

Fifteen years ago, she co-wrote “Israel’s Silicon Wadi: The forces behind cluster formation”, a paper extolling the nation’s virtues as an incubator for technology ideas.

Along with government policy and a spirit of entrepreneurship, de Fontenay notes that many Israeli businesspeople have little reverence for authority, “which is a helpful thing if you’re forging your own path”.

"The key missing element that China is looking for today is technology, and Israel is basically a supermarket for technology."

The nation’s small population has also been an asset rather than a liability.

Forget six degrees of separation – in Israel, courtesy of strong military and business networks, most people in the technology and venture-capital sectors know each other well.

“There’s a closeness that’s very, very helpful because essentially with venture capital ... you’re taking a punt on people that you don’t know,” de Fontenay says.

“[With Israel] it’s a big difference when you take a punt on a person that you and all your close friends know very well, and who you’ve seen perform under situations of stress.”

According to the IVC Research Centre in Tel Aviv, Israeli high-tech companies raised an all-time annual high of US$4.8 billion in 2016, with the average financing round reaching US$7.2 million.

Kobi Rozengarten, managing partner at Jerusalem Venture Partners (JVP), says the Israeli venture-capital market for technology innovations is going from strength to strength on the back of rising domestic and international participation.

Whereas American and European investors once dominated the market, major Japanese and Chinese companies are now also targeting Israeli ingenuity.

“It’s making it a very busy environment,” says Rozengarten, who notes that JVP has in the past couple of years helped facilitate Sony’s purchase of Altair Semiconductors and Huawei’s acquisition of database security firm HexaTier.

“It’s clear that the key missing element that China is looking for today is technology, and Israel is basically a supermarket for technology. If you want to see trends and be exposed to technology, you come to Israel.”

In fact, he contends that Israel, as a small market, is a better fit for Chinese companies than the US.

“Israeli companies don’t plan to conquer the Chinese market. We believe that we need to work with Chinese partners to do that, while American-based companies believe that they need to own the consumer in China, which can create some conflict.”

Military experience = start-up strength in Israel

As part of the compulsory military service for most Israelis aged 18 and over, men spend up to three years in the defence forces, while women serve two years.

Rather than seeing this as a burden, many Israelis credit military service with being a driving force behind their country’s high-tech success.

De Fontenay says many tech specialists have come through the ranks of military intelligence units, including the famed cyber unit 8200.

“People who have been in the Israeli military view it as a rather entrepreneurial experience, whereas the rest of us aren’t used to thinking of the military as a place that encourages original thinking. Being a 20-year-old who is put in charge of a unit or a tricky situation [can change their life].”

"The Israeli approach is different – we do things first and plan them later."

Menny Barzilay, a former army captain who is now CEO of cyber security firm FortyTwo, says the difference between the military experience in Israel and many other nations is that Israeli military service is mandatory.

The best and brightest talent are compelled to do their bit, whereas in some countries it is seen as a last-resort career.

“In Israel, because the army mostly consists of 20-year-old kids, it is an exciting place to be,” Barzilay says.

“You get new people with new approaches and new knowledge all the time.”

Limits to the Israeli approach

The rise of Silicon Wadi is impressive, but barriers still exist. A lack of scale means Israeli companies typically have to be the target of international investors if they want to have real clout.

Guez, who will relocate to the US next year as part of her plan to grow Papaya Global into a US$100 million net revenue company, says achieving success in the US is still the holy grail for most of her colleagues.

Many of them sell their start-ups to international enterprises, and then start again with a new idea. The emphasis, inevitably, is on international achievement.

“We understand that we are in Israel, but we always need to think globally.”

4 reasons Israeli start-ups thrive

Israeli innovator, cyber security strategist and former army captain Menny Barzilay gives his take on his country’s high-tech success.

Why is Israel’s technology ecosystem so good?

“Israeli prime minister Benjamin Netanyahu has commented that there are not a lot of benefits to being a small country, but the ability to create a successful ecosystem is definitely one of them.”

What factors stand out?

“Number one is culture. In Israel, you can walk down the street and see the CEO of a big company and you can approach them and say, ‘Hey, I have a company, can we sit together and talk about that?’ And many times they’ll say, ‘Let’s talk’, because if you don’t know this person your mother knows his mother. That’s the way it is; everyone knows everybody.

“If you were to do that in countries like China or India, where the hierarchies are very clear, this would be a big mistake, but in Israel there are no boundaries.

“Another big factor is our approach to failure. We don’t see failure as a big deal.

"If you fail three times with a start-up company, and you come to me and want me to invest in your fourth company, I’ll probably consider you as someone with a lot of experience who is in a very good position to do a start-up compared with a kid who has never tried once.”

How has military experience helped you and others?

“It’s a very well-organised system and if you have the ability, for example, to be a cyber security guy, the system will identify that and put you in the right place.

“When you leave the army you’re still a kid; you’re 21 or 22 and have no obligations, but on the other hand you’re already very mature. You have made big decisions, you have carried a gun. You have played with the big guys. This is a unique experience.”

Do you see parallels between Silicon Valley and Silicon Wadi?

“The most important similarity is that both have an ecosystem where it’s all about creation and invention. However, I still think the Israeli approach is different – we do things first and plan them later. It’s unique to Israel.

“When you work with Israelis you’ll get results very fast, but they won’t be very clean. We’re very orientated to results and our approach has many more advantages than disadvantages.”

5 Israeli smart sectors

Cyber security – standouts such as Check Point and CyberArk are leading the fight against cyberthreats.

Transport and navigation – driverless car system Mobileye and navigation app Waze have made it big.

Aviation and drones – military development has helped Israel become the world’s largest exporter of drones. There are more than 30 companies in the commercial drone space, including Airobotics, Arbe Robotics and Flytrex.

Water and agricultural technology – in this arid region, water and desalination innovations have been critical. SupPlant, for example, is a system that collects real-time crop data on farms, and if it detects water stress in plants, can automatically adjust irrigation flows.

Artificial intelligence and robotics – AI-based robotic devices are on the rise, including ElliQ, an emotionally intelligent robotic companion that helps keep the elderly active.