Loading component...

At a glance

- Productivity growth in most developed countries has been stagnant for many years.

- The RBA focuses on two main measures of productivity: labour productivity and multifactor productivity.

- Some economists believe old ways of measuring productivity do not account for technological progress.

As economic indicators go, productivity is one of the more attention-grabbing measures. The reason is clear – productivity growth is seen as a driver of real wages, purchasing power and overall living standards.

What exactly is productivity and how is it measured? The Productivity Commission – the Australian Government’s research and advisory body on a range of economic, social and environmental issues – defines productivity as “a measure of the rate at which output of goods and services are produced per unit of input”. Those inputs include labour, capital and raw materials.

Like most other central banks around the world, the Reserve Bank of Australia (RBA) focuses on two main measures of productivity. The first is labour productivity, which the RBA notes is “the output per worker or per hour worked”.

The second is multifactor productivity (MFP) which assesses the “output per unit of combined inputs”. Those units typically include labour and capital, but can be expanded to account for energy, materials and services.

MFP provides a more nuanced perspective on the operational performance of businesses and is regarded as a better measure of technological change and efficiency improvements than labour productivity.

Crunching the productivity numbers

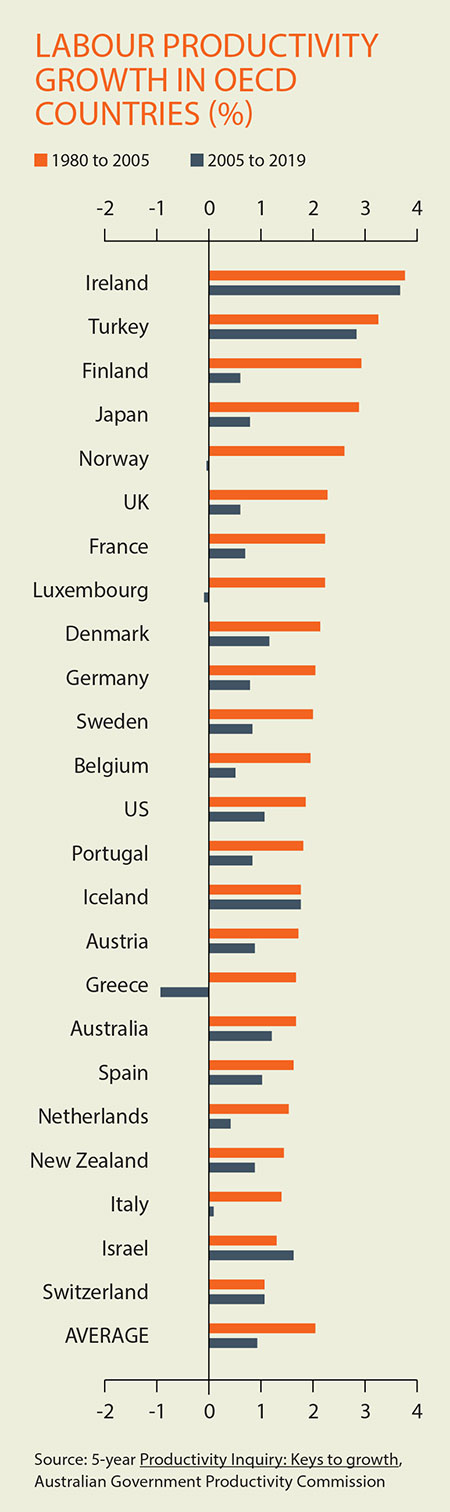

Falling productivity levels are a worldwide issue. A 2024 Productivity Commission inquiry found that just one advanced economy, Israel, had recorded higher average annual productivity growth after 2005 than in the decades before it.

This is a far cry from the “golden years” of productivity growth in the 1950s, 1960s and early 1970s, when many countries boomed on the back of strong manufacturing sectors and dynamic employment markets.

University of Canberra economist Dr John Hawkins, whose résumé includes roles at the Reserve Bank of Australia (RBA) and the Hong Kong Monetary Authority, says that in Australia, productivity has “flatlined”. Some put the blame on record-low unemployment, which has resulted in the long-term unemployed joining the workforce and stunting productivity, at least initially.

Hawkins adds that the modern dominance of service industries, in which there is less capacity to lift productivity compared to former stronghold industries, such as manufacturing and agriculture, is also a factor.

The RBA notes that the Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS) is responsible for measuring outputs and inputs for different industries, sectors and the economy. Productivity, as such, is not measured directly, but is calculated by dividing a measure of output by a measure of inputs.

"If you’re looking at multifactor productivity, most of it’s been driven by technological progress, but most of the technological progress appears as computers from overseas are getting cheaper. It doesn’t appear at all as productivity growth in Australia. It appears technically as a favourable terms-of-trade shock."

It reports that output, measured in terms of gross domestic product (GDP), refers to a quantity of goods and services produced during a given time. For an industry or sector, it is usually measured by gross value added (GVA), which is the total value of goods and services produced, less those goods and services used in the production process. Output for the whole economy can be derived by calculating GVA across industries.

With inputs, labour and capital are the two main elements. Labour is typically measured as hours worked among people who are employed. Capital is measured as the flow of services coming from capital stock, which includes buildings, machinery and equipment, livestock and plantations.

At the ABS, Bjorn Jarvis is head of the labour statistics team that produces statistics on the hours people work. He says producing “more holistic” statistics on MFP is important, but it is also more complex and time-consuming.

“That’s much more challenging, because you’re talking about bringing in more elements. This is why we calculate MFP on an annual basis, compared with quarterly insights into labour productivity.”

Understanding technology's impact

As the global economy is increasingly built around services and human performance, rather than just the making of goods, some critics argue that productivity is no longer the metric that matters the most as a measure of organisational performance.

A common critique is that standard measures such as labour productivity and MFP do not adequately capture gains from innovation related to information and communications technology (ICT).

However Professor John Quiggin at the University of Queensland’s School of Economics believes GDP statistics still provide valuable information to policymakers about the short-term state of the economy. In an economy subject to dramatically divergent trends, however, he questions their usefulness as a long-term measure.

“These aggregate index numbers are ceasing to be incredibly useful,” says Quiggin, who observes that the national accounting system, of which GDP is a central part, was developed in the 1930s to measure the workings of the industrial economy when agriculture, mining and manufacturing dominated.

“The important point is that such a [traditional] economy now accounts for maybe half of economic activity,” he says.

Today, Quiggin adds, the growth in the production and dissemination of information and ICT has been so fast that it defies traditional methods of measurement.

"There will always be challenges and limitations around the measurement of productivity, which the ABS addresses through improvements in data and methods. It continues to be important as a key long-term measure of change in the economy."

“If you’re looking at multifactor productivity, most of it’s been driven by technological progress, but most of the technological progress appears as computers from overseas are getting cheaper. It doesn’t appear at all as productivity growth in Australia. It appears technically as a favourable terms-of-trade shock.”

Jarvis remains a fan of productivity as a metric, stating that it offers a consistent and indispensable point of reference for understanding how the Australian economy and its industries are changing.

“There will always be challenges and limitations around the measurement of productivity, which the ABS addresses through improvements in data and methods,” he says. “It continues to be important as a key long-term measure of change in the economy.”

Can we lift productivity again?

The consensus is that it will not be easy to lift productivity growth.

In Australia, the Productivity Commission is pinning its hopes on five key themes – building an adaptable workforce; harnessing data, digital technology and diffusion; creating a more dynamic and competitive economy; efficiently delivering government services and securing net-zero greenhouse emissions at least cost.

"Most organisations think it’s a skill issue and that they need to upskill their people. Or they may think it’s an employee motivation issue and that they just need to encourage their people to work harder or smarter. The thing they miss is these work frictions."

It adds that a services-based economy requires investment in better teaching and innovation in educational institutions. Better-targeted skilled immigration could also make a difference.

According to Quiggin, the most hope for productivity growth rests with “technological progress”.

“We could see some very big improvements from artificial intelligence,” he says. “What we won’t see, I think it’s safe to say, is big improvements in productivity in the goods-producing sector of the economy, because no country in the rich world has seen that. We’ve picked all the low-hanging fruit there.”

Jarvis adds that some economists believe low job mobility, especially among younger workers, could make it harder for businesses to become more efficient and productive. ABS figures from July 2024 show that Australia’s job mobility rate has fallen for the first time in three years, back to its historically low level just before the pandemic.

This is despite predictions that COVID-19 would lead to the Great Resignation as people re-evaluated their lives and careers after the pandemic. However, the ABS observed that in the 12 months prior to February 2024, only about 8 per cent of employed people, or 1.1 million people, changed their employer or business.

This was down from 9.6 per cent in February 2023 and back to what Australia typically experienced during the five years leading up to the pandemic.

Hawkins is not overly optimistic that Australia, or other countries, can quickly ramp up productivity, because elements such as increasing skilled immigration, improving education and shifting the skills base take time.

“There’s almost no quick fix to productivity,” he says.

Hawkins says there are also concerns about a lack of competition and dynamism in the Australian economy because of duopolies or oligopolies in areas such as banks, telcos, airlines and supermarkets.

“There’s not a lot of competition and, as a result, there is no hard pressure put on companies to improve productivity.”

Why younger SME entrepreneurs are key to productivity growth

Less friction = more productivity

In the quest for better employee productivity, the focus of many organisations is on training and upskilling. Neal Woolrich, director of Human Resources Advisory at Gartner, says that is not sufficient.

“There’s an untapped opportunity to drive productivity,” Woolrich says. “Most organisations think it’s a skill issue and that they need to upskill their people.

Or they may think it’s an employee motivation issue and that they just need to encourage their people to work harder or smarter. The thing they miss is these work frictions.”

Gartner research identifies four such frictions:

- Misaligned work design – employees may not know how they should be getting their work done.

- Overwhelmed teams – they are uncertain about task priorities.

- Trapped resources – budgets and resources are set in stone even if circumstances change.

- Rigid processes – employees’ work slows while they wait for leaders to make decisions.

Woolrich is confident that, done properly, the work-from-home trend can enhance the productivity of workers.

Defining and measuring employee productivity can be difficult, but one common way is to simply divide the company’s total revenue by its number of employees.

Typical ways that businesses can improve their productivity include increasing technical efficiency, embracing technological progress and organisational change, and using technology to maximise returns from scale.

Regardless of the measures, Woolrich advises business leaders to be “absolutely ruthless” about regularly monitoring and refining the organisational design of their operations.

“Organisational design should be an ongoing discipline,” he says.

How Singapore measures productivity

Singapore has long been regarded as one of the world’s best economic performers, but even the South-East Asian powerhouse struggles when it comes to labour productivity.

While labour productivity per actual hour worked (AHW) soared during COVID-19, by 2023 it had dropped to -2.4 per cent, meaning the nation had not met the Economic Strategies Committee’s ambitious target of 2 to 3 per cent per annum of labour productivity growth.

Labour productivity can be computed in terms of real value added (VA) per actual hour worked (AHW) or real VA per worker.

In Singapore, real VA per worker is most cited because VA and employment data are readily available and easy to calculate. However, using AHW as a measure of labour input is thought to better capture the actual amount of work in an economy.

As a result, this measure has become more popular in Singapore in recent years, especially given the rising share of part-time workers in the economy and cyclical changes in the hours worked by full-time employees.