Loading component...

At a glance

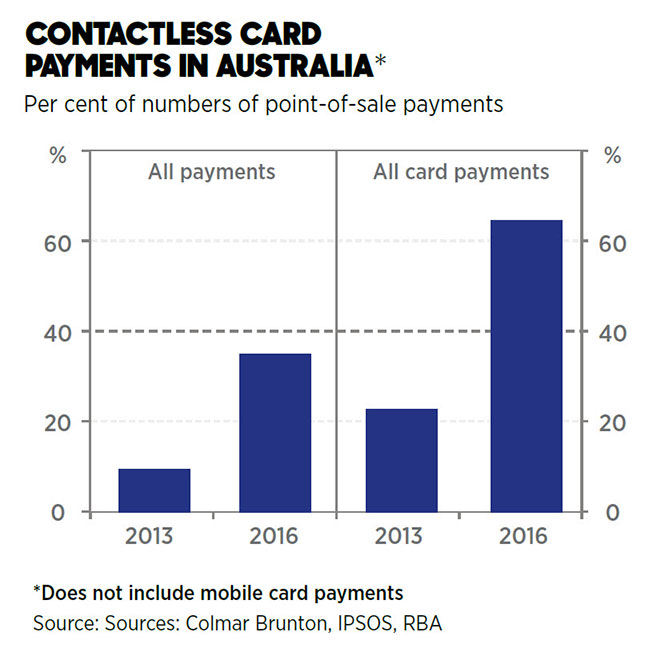

- Card, online and contactless payments are increasingly popular, but a completely cashless society can discriminate against certain groups, such as the elderly and unbanked.

- Cashless transactions can be inconvenient in rural areas, where unreliable telecommunications or digital banking may disrupt payments.

- Technology and anti-fraud training can help people catch up and use cashless payment methods.

When Philadelphia councillor William Greenlee heard that his regular coffee shop had banned cash payments, it did not sit well with him.

In a city where more than 12 per cent of the population are unbanked – that is, they do not have a bank account or access to a credit card – Greenlee felt the move discriminated against the poor, minorities and immigrants.

“I thought, ‘Gee, that’s strange’ … It just didn’t seem right to me that I could walk into that coffee shop, and [because] I have a credit card I can get my cup of coffee,” he says, “but someone is standing by me that has the currency of the United States of America, which has been used since Benjamin Franklin walked around here, and they can’t get a cup of coffee and a doughnut.”

Greenlee introduced a bill proposing to stop retailers and restaurants from refusing to accept cash. Despite some pushback from businesses on the grounds that it infringes on their rights, the law was fully enforced from 1 October 2019.

Greenlee is satisfied. “I’ve always thought that one of the things that government should do is to try to ensure fairness, and it just did not seem fair that people were basically told ‘we don’t need your business here’.”

Grappling with a cashless future

As the world increasingly favours card, online and contactless payments, society is grappling with the implications, good and bad, of a possible cashless society in the near future.

Steve Worthington, a professor in the Faculty of Business and Law at Swinburne University of Technology, says reports of the death of cash and cheques may be exaggerated.

“I can agree with a less-cash society, but I can’t ever see us getting to a cashless society and that’s across the world,” says Worthington.

He points to a backlash against going cashless in some countries, which has seen Amazon, the pioneer of cashier-free stores, agreeing to accept cash at some of its brick-and-mortar outlets.

Even in advanced countries such as Australia, insisting on electronic payments can cause headaches, especially in rural areas where unreliable digital banking or telecommunications networks can disrupt cashless payments.

The potential for data breaches of customer information on online platforms also raises security concerns.

“People are a little nervous about being left short of a payment mechanism if the telecom system goes down and [they don’t want] to put all their eggs in one basket vis-a-vis staying entirely in the digital sector,” Worthington says.

Even in Sweden, a cashless stronghold where already thousands of people have implanted microchips in their hands to allow them to pay for public transport and retail goods with a wave of their hand, there has been concern about digital-only payments.

About 85 per cent of transactions in Sweden are already digital via cards or mobile platforms, but the Swedish central bank, the Riksbank, has proposed that big banks must provide ATMs in all areas across the nation.

"[Cash] is going very quickly. We are not against digital development, but so long as coins and bills are legitimate forms of payment, it must be up to every individual as to how they will pay.”

Pensionärernas Riksorganisation (PRO), the peak body representing Swedish pensioners, has backed the move.

While it is not opposed to the cashless trend, PRO suggests the switch to digital payments is occurring too quickly, leaving some people behind as facilities and services such as restaurants, bars, public transport, swimming pools, parking places and even public toilets abandon cash.

“[Cash is] going very quickly,” says PRO president Christina Tallberg.

“We are not against digital development, but so long as coins and bills are legitimate forms of payment, it must be up to every individual as to how they will pay.”

She says about a million people in Sweden are not familiar with digital systems; these include 600,000 over the age of 65.

“Many have difficulties remembering their bank codes and are therefore not comfortable at an ATM,” Tallberg says.

To combat this tech-phobia, PRO has for some years provided educational courses for people wanting to improve their computer, mobile and tablet skills.

Cyber security issues and cashless payments

While cash payments are declining in some markets, the digital road is not always smooth.

In a setback for Hong Kong’s plan to develop into a smart banking centre, the city’s Monetary Authority has ordered digital wallet operators to suspend auto transfers via the new Faster Payment System to top up Octopus cards (contactless stored-value smart cards used to make online and offline electronic payments) after a number of fraud cases occurred.

James Wong CPA, director of Asia financial technology and business services at UBS Hong Kong, says the issue highlights the fact that cashless payments must still pass security tests, given that hackers are seeking to target electronic funds and data.

“Cyber security is also of paramount importance at the back end,” he says.

Wong says the adoption of non-cash payments has been starkly different between Hong Kong and Mainland China.

Whereas credit cards and Octopus cards still dominate the Hong Kong market, China has been able to leapfrog straight to smart payments through mobile apps such as Alipay and WeChat Pay.

With most Hong Kong consumers being comfortable with cards, Wong says Visa, Mastercard and American Express have simply introduced related contactless pay-wave options, “which are incremental innovations on existing infrastructure. So [most people] feel that cards are convenient.”

In Singapore, there is a familiar refrain of millennials embracing innovations such as tap-and-go payments, while the elderly remain cautious adopters.

Chia Tek Yew, head of KPMG Singapore’s Financial Services Advisory practice, says millennials and younger shoppers are “self-selecting” with their choice of retailers.

“When they go to a food court or even if they go to a fast-food chain, they will only go to those where electronic money is accepted,” he says.

Chia agrees mainland China has taken cashless payments to another level, with “even beggars on the street accepting WeChat Pay”.

In Singapore, however, he says the popularity of dining at cheap hawker food centres means cash is still king in many areas of the city. Tasks such as private tuition, gardening and other domestic help services are also usually paid for with cash. This means the switch to cashless options has not been as fast as once expected.

“It will take time for adoption because the resistance is obvious from [business people such as] hawkers who like to have cash in hand, so they can pay their suppliers.”

Tech and anti-fraud training required

Technology training (such as PRO’s educational courses) and anti-fraud training are measures that can help and support citizens as cashless payments become the norm.

David Glance, director of the University of Western Australia Centre for Software and Security Practice, says education can prove helpful.

“[However] there are still scams that are being carried out on the elderly where they are asked to buy store gift cards and send the [security codes] to scammers, so it is going to be a challenge.”

Ironically, Glance says, some elderly and disadvantaged groups will likely go cashless before the rest of society because of the introduction of electronic welfare cards, which control purchases.

“There is probably also room for other schemes that would support the unbanked population, as there is in China with mobile phone payments through WeChat, but there will be resistance to abandoning cash altogether.”

Meanwhile, with the cash-ban laws in Philadelphia set to start, Greenlee is pleased he has been able to support the elderly, minority groups and disadvantaged.

While he acknowledges arguments that credit and smart payments will dominate millennial spending traits within a decade or less, he is unrepentant.

“Millennials aren’t the only people in Philadelphia,” he says.

“We have seniors, and a lot of the people who are unbanked tend to be minorities. It shouldn’t be an us-and-them situation to buy a basic product if people have the currency to do it.”

Pros and cons of cashless

Fast and efficient

Convenience is clearly driving the use of tap-and-go and other forms of digital payments such as mobile apps, says University of Western Australia security expert David Glance.

With such technology, consumers do not have to go to an ATM or handle cash. They can also easily keep track of what they spend through online tools.

“Consumers are paying for this convenience, of course, by paying charges on these transactions – either explicitly but, more often than not, built into the price of the goods they are buying,” Glance says.

Clear money trail

Glance says governments clearly see cash as a major enabler of the grey and black economies, “whereas electronic payments are trackable”. There is also the expense of managing the production and disposal of cash in circulation.

Social tool

KPMG partner Chia Tek Yew says social welfare digital wallets will become increasingly popular, allowing money to be loaded onto smart phones for basic payments.

At the same time, governments could use such digital wallets to control purchases; for example, exempting purchases of cigarettes, alcohol and other such unhealthy discretionary items for welfare recipients.

“This evolution with e-payments is not just about replacing cash because it is cumbersome and expensive for governments to maintain; you can actually use it for the right social causes,” Chia says.

Privacy edge

An attraction of cash is the three As – “It’s anonymous, it’s accepted nearly everywhere and it’s authentic,” Worthington says.

“There’s something about cash – you can touch it, hold it, feel it.”