Loading component...

At a glance

By Adam Baidawi

Bob Iger doesn’t do things by halves. His tenure as Disney CEO has been defined by monster acquisitions that have delivered monster revenues and returned Mickey Mouse to the top of the Hollywood Hills.

Iger’s most recent gamble was a US$4 billion acquisition of Lucasfilm, the home of Star Wars.

Disney’s first foray into the galaxy far, far away was The Force Awakens, which has exceeded US$2 billion in box office revenue since being released in December 2015.

For Iger, that return is par for the course in a string of deals that has seen Disney’s share price quadruple since 2005.

All 1000-watt Disney smile and salt-and-pepper hair, Iger has quickly built himself a reputation that’s equal parts business prowess and emotional intelligence. These ingredients have been the keys to each of his trademark moves.

Within days of being appointed Disney CEO in 2005, and with the company in disarray following the exit of long-time CEO Michael Eisner, Iger entered his first board meeting and unapologetically proposed the first of his now trademark acquisitions.

Disney soon acquired animation titan Pixar for US$7.4 billion. Iger was capitalising on a generation’s worth of nostalgia, and his Pixar bet paid off.

The 2010 hit Toy Story 3 raked in more than US$1 billion at the box office worldwide, which is comfortably more than the previous two films in the animated series combined.

Shortly after the Pixar acquisition, Iger struck again. In 2009, he inked a US$4 billion deal for Marvel Entertainment, which is famed for comic book characters such as Spider-Man, Iron Man and X-Men.

This acquisition proved just as strong, with the studio releasing a string of big earners, including Thor, The Avengers and Guardians of the Galaxy. Marvel is now a business superhero for Disney – a juggernaut that has moviegoers flocking to cinemas worldwide.

While Pixar and Marvel Entertainment have been the reliable profit-generator tent poles that have fuelled Disney’s resurgence under Iger, it’s the 2012 acquisition of Lucasfilm that was perhaps his most impressive negotiating feat and possibly his most necessary accomplishment as Disney CEO to date.

It’s a lesson in how to move a business forward.

Trouble in the mouse house

Many people regard Disney as an ageless cartoon studio thanks to pioneering animations such as Snow White, hits such as The Lion King and iconic characters such as Mickey Mouse.

But despite a company value of US$180 billion that towers over fierce media competitors such as Time Warner and 21st Century Fox, Disney has had its share of problems in recent years.

Its televised sports network, ESPN, accounts for nearly half of the company’s operating income, and it is feeling the pain of consumers pulling away from subscription-model television.

In the past three years, the channel has lost nearly seven million cable subscribers. Lower fees and shrinking ad revenues due to its decreased reach have turned ESPN into Disney’s greatest weakness.

When subscription numbers dropped in 2015, Disney shares fell more than 9 per cent on one August day. Even ESPN’s digital efforts have brought disappointment: last year, it cut respected sports analyst Bill Simmons and his Grantland blog.

Disney’s film business hasn’t been infallible, either. In 2013, Frozen became the highest grossing animated film of all time, but this was offset by disastrous live-action releases such as John Carter and The Lone Ranger, which cost the studio hundreds of millions of dollars.

"The price was a huge capital outlay at US $4 billion "

Star Wars: A new hope

The arrival of the Star Wars franchise at Disney was decades in the making. In the mid-1970s, Lucas and producer Gary Kurtz pitched the first Star Wars film to Disney, who rejected it.

The pair eventually made the film with Fox, who fretted that the loosely scripted space flick was borderline unmarketable – right up until it exploded into global consciousness in 1977.

Hollywood then scrambled to replicate its star-kissed formula, greenlighting Alien, reviving Star Trek and even sending James Bond into space in Moonraker. For Christmas 1979, Disney joined the party with The Black Hole – at the time its most expensive production.

But despite its cute robots, deep space effects and epic laser battles, The Black Hole simply consumed Disney’s money while audiences waited for the next Star Wars instalment, The Empire Strikes Back, released in 1980.

Lucas, meanwhile, had used clever negotiation to retain the Star Wars merchandise rights – not considered a big deal in the mid-1970s – as well as sequel rights. Star Wars toys sold in their millions and all signs pointed towards a sequel turning into further box office gold.

This made Lucas not only the Star Wars creator but also, courtesy of his Lucasfilm production company, the owner of a lucrative media brand.

Over the next three decades, Lucas would not only executive produce two Star Wars sequels, The Empire Strikes Back and Return of the Jedi, but also direct three prequels – Star Wars Episode I: The Phantom Menace; Star Wars Episode II: Attack of the Clones; and Star Wars Episode III: Revenge of the Sith – the first two of which were widely regarded as disappointments.

By 2011, with retirement looming, George Lucas was thinking about a sale of Lucasfilm and a safe home for the Star Wars legacy.

Iger had seen this situation before. He had painstakingly persuaded Steve Jobs to sell Pixar and understood the importance that creators put on their legacy.

For Lucas, a deal had to offer a chance at redemption after the critical slaughtering of the Star Wars prequels.

Iger says Lucas told him in late 2011 that if Lucasfilm was sold to anyone, it would be Disney. Six months later, Lucas called back and the deal was done.

Disney paid Lucas relatively much more for Star Wars in 2012 than it would have in 1975. Then again, Disney under Iger had shown it could make money paying big prices, such as the US$7.4 billion forked out for Pixar. Just as importantly, the cinematic partnership made sense for both sides.

“It is wrapped in the same kind of language – ‘A long time ago in a galaxy far, far away’ – as most successful Disney movies,” says Chris Taylor, author of How Star Wars Conquered the Universe.

“We’ve never lost our love for fairytales, no matter where or when they’re set.”

Return of the franchise

When the Disney-Lucasfilm deal was announced in 2012, not everyone thought it was brilliant.

“There was always a question about the price,” says Evan Lucas, market strategist at IG.

“It was considered fair; however, there is no escaping it was a huge capital outlay at US$4 billion.”

Often overlooked is the fact the Lucasfilm deal had some cloaked assets.

There’s Industrial Light & Magic, one of the film industry’s largest visual effects companies, and Skywalker Sound, the aptly named sound effects and post-production company that has won 16 Academy Awards.

In addition to getting its hands on Star Wars, Disney also got a slice of the lucrative Indiana Jones pie. The deal also delivered Lucasfilm president Kathleen Kennedy, a profit-maker who is rumoured to be Iger’s possible Disney successor.

However, all of that would have mattered little if Disney hadn’t been able to deliver a successful new Star Wars film. Under Kennedy’s management, the first new movie, The Force Awakens, released in December 2015, has been a raging success.

Loaded with action and nostalgia in equal measure, the film pleased old and new fans and enjoys a 92 per cent approval rating on review aggregation site Rotten Tomatoes.

It’s Disney’s highest-grossing film of all time, the highest-grossing film in North American history, the highest-grossing of all Star Wars films and the film that has earned the fastest US$1 billion.

Disney’s creative approach primed The Force Awakens for business success. Critics have noted the film sometimes feels like a remake of the original Star Wars. Evan Lucas calls it “safe” but argues any other approach would have carried vastly higher risks for Iger and his team.

“It had to deliver positive EPS [earnings per share] immediately or it would have been met with a negative wave of hare investment and some very tough questions aimed at management’s strategic thinking,” he says.

As Lucas discovered in the 1970s, the real prize in the Star Wars universe is merchandising: 76 per cent of the US$42 billion revenue from pre-Disney Star Wars came from physical goods, such as toys and books. What organisation is better than Disney to capitalise on this?

Already on a roll thanks to animation giant Frozen, Disney’s licensing and merchandising is best in class – everything from theme park rides to dresses to a kaleidoscope of kid-friendly toys.

Led by Frozen princess Elsa, sales of the film’s paraphernalia actually grew 13 per cent last year, which is astonishing considering the movie was released in 2013.

Disney’s booming consumer products division reported US$971 million in revenues in early 2015. In December 2015, analysts predicted The Force Awakens merchandise would generate US$5 billion over a 12-month period.

The trend had already become clear the month before when gaming powerhouse Electronic Arts released Star Wars Battlefront, the latest in a long line of Star Wars video games.

Despite mixed reviews, it has sold more than 12 million copies, many of which flew off the shelves before The Force Awakens was released.

Disney’s strategy has been impressively diverse, even by its own standards.

It struck Star Wars licensing or marketing deals with makeup company CoverGirl, sandwich franchise company Subway and even car manufacturer Fiat.

However, the big merchandising success has been the BB-8 Droid. The app-enabled device was credited with significantly boosting 2015 Christmas toy sales in the US.

“The introduction of BB-8 is expected to be the biggest one-off merchandise product of the Star Wars franchise since R2-D2,” says IG’s Lucas. “Disney merchandise return will only increase on specialised short films that increase character stories.”

It should be noted that despite the popularity of its Frozen heroines, Disney was widely considered to have missed a marketing opportunity for failing to produce a variety of toys depicting The Force Awakens’ central figure, the female character Rey.

"We’ve never lost our love for fairytales, no matter where they’re set.”

Most crucially to the future of Star Wars under Disney, the new film appears to have won the cultural appreciation of even the most die-hard fans.

Fears about the creative implications of Disney controlling Lucas’s vision appear to be quelled for now.

It’s the same trick Disney managed with Marvel. The studio knows how to take care of a long-established entertainment brand. It’s even kept a low profile in public relations.

“Lucasfilm is better at PR than Disney,” says author Taylor.

“The more Disney has let its subsidiary take the lead in this area – which is most of the time – the better the result. It has wisely ceded the creative side to Lucasfilm, too.”

The quest for new markets

Iger and Kennedy still have a few territories to conquer. The Force Awakens performed relatively poorly in China and South America, where Star Wars nostalgia is weaker.

China is poised to become the world’s biggest movie market, so the quest for Chinese success will continue over the next few years.

In the meantime, Disney has more Star Wars films on the production line.

The franchise’s first-ever spin-off film, Rogue One: A Star Wars Story, is due to arrive later this year. Following it will be two Force Awakens sequels, a Han Solo spin-off and further sequels down the track.

And lest this universe be confined to a mere two dimensions, the Disney boss has already revealed plans for a theme park: Star Wars Land. As ever, Bob Iger doesn’t do things by halves.

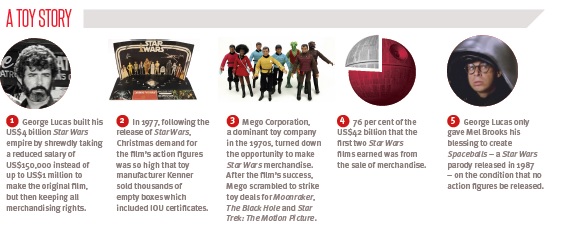

A Toy Story

George Lucas built his US$4 billion Star Wars empire by shrewdly taking a reduced salary of US$150,000 instead of up to US$1 million to make the original film, but then keeping all merchandising rights.

In 1977, following the release of Star Wars, Christmas demand for the film’s action figures was so high that toy manufacturer Kenner sold thousands of empty boxes which included IOU certificates.

Mego Corporation, a dominant toy company in the 1970s, turned down the opportunity to make Star Wars merchandise. After the film’s success, Mego scrambled to strike toy deals for Moonraker, The Black Hole and Star Trek: The Motion Picture.

76 per cent of the US$42 billion that the first two Star Wars films earned was from the sale of merchandise.

George Lucas only gave Mel Brooks his blessing to create Spaceballs – a Star Wars parody released in 1987 – on the condition that no action figures be released.