Loading component...

At a glance

- The valuation for the global digital health market is expected to exceed US$639.4 billion (A$917 billion) by 2026.

- In the past, the medical profession has viewed telehealth services as useful in restricted scenarios, but advancements in medical telemetry devices have expanded its potential.

- A large shift to digital health services could change many aspects of the medical profession, including service delivery, medical training and the screening of patients, but it will also have implications for medical insurance.

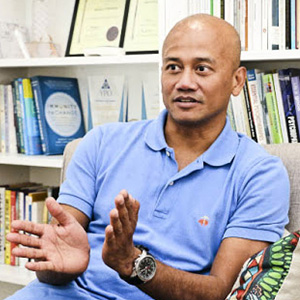

Azran Osman-Rani envisages the day when general practitioners (GPs) prescribe a digital app for patients in the same way that they now so commonly prescribe a drug.

The serial entrepreneur is co-founder and CEO of Naluri, a digital therapeutics company in Malaysia that uses behavioural science, data science and digital design to build patients’ mental resilience and target chronic disease.

Osman-Rani believes a coordinated online approach from medical practitioners who address mental health issues while treating conditions such as heart disease, diabetes and cancer is the key to the future of medicine.

“The reason why we do it together is because we believe these things need to be addressed in an integrated way, whereas traditional healthcare looks at them separately,” he says.

Stanford-educated Osman-Rani has a history of spotting business trends. His latest brainchild, the Naluri app, allows patients to access an expert team of health and fitness coaches, dietitians, medical advisers and pharmacists, all only a click away.

Osman-Rani’s associated goal is to get insurance companies to treat such medical advances as a standard claimable item, rather than some isolated experiment. He concedes that will require clinical research to prove the value of such an approach, as well as convincing insurance companies “that the efficacy of digital apps is comparable to drugs. That’s a big mindset shift, and to me that’s a multi-year battle.”

Nevertheless, he is up for the fight.

A new age

Naluri is just one story in a time when the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic has put the spotlight on digihealth. Research consultancy Global Market Insights has estimated in a report that the market valuation for digital health – which includes categories such as telehealth, health information technology, wearable devices and personalised online medicine – stood at US$106 billion (A$148 billion) in 2019, and will rise to over US$639.4 billion (A$917 billion) by 2026.

Social distancing and life in lockdown have fast-tracked the use of telehealth consultation between doctors and patients following restrictions on face-to-face appointments.

The impetus has encouraged several governments to revise and amend regulatory policies relating to digital health services, while the increase in the use of devices such as smartphones, tablets and wearables is also driving the market.

In Australia, telehealth options have largely been the reserve of rural and remote patients, until now. The Australian Government has moved to expand access to Medicare-subsidised telehealth services, including GP services and some consultations provided by other medical specialists and nursing practitioners.

The Royal Australian College of General Practitioners (RACGP) estimates that about 40 per cent of doctors’ consultations are now being done via phone calls and videoconferencing. Spokesperson Dr Nathan Pinskier, a Melbourne-based GP and prominent figure on Australia’s digital health scene, says the Medicare reform shapes as a game changer, provided that it is maintained post-pandemic.

“The government basically deregulated something that we asked for well over a decade ago,” he says.

Pinskier says that, in the past, the medical profession had the view that, while telehealth services could be useful in restricted scenarios, a face-to-face consultation was “still the rolled-gold best option”. “Now that may not be so true,” he says, noting the evolution of sophisticated medical telemetry devices that can support digital treatments through remotely monitoring various vital signs of patients.

Better internet, wi-fi and Bluetooth technology also make a difference, although Pinskier says for now the vast majority of GPs consulting remotely have been using the humble telephone rather than videoconferencing platforms. “So, while we have come a long way, perhaps we haven’t!”

CPA Library resource:

With telemedicine convenience and efficiency can also come added risks for GPs and other medical practitioners, according to Drew Fenton CPA, director of Fenton Green & Co, a leading player in the Australian medical indemnity insurance market.

“History will show you that risk is amplified by change,” he says. “Why? Because it’s new, because we are not quite familiar with it, and because various scenarios have not fully played out. So, we haven’t yet learned from this change experience.”

Fenton raises the spectre that GPs using telehealth consultations may not always be able to determine, for example, if a patient actually just has a headache, or whether there are underlying symptoms of more serious conditions such as alcoholism or depression.

When consulting over a video screen, can doctors pick up on important cues such as body language, a person’s attire or whether there is alcohol on the breath? “You can get all of those nuances through face-to-face consultation.”

The implications for medical indemnity insurance could be significant, but Fenton says insurers are unlikely to deny a claim if medical practitioners miss a condition using telehealth, because the defence will be that they are simply following industry regulations and guidelines.

“The real risk mitigation in my view must, therefore, come from the medical associations working in conjunction with the insurers to study data and understand potential problem areas.”

The profession should also further ramp up its focus on cybersecurity risks, given the greater reliance on technology platforms, Fenton adds.

For its part, the RACGP has warned patients to be wary of “corporate telehealth pop-ups” that have proliferated during the pandemic, along with the increase in telehealth and telephone consultations. One new service lets customers get quick prescriptions via an app after consulting with a GP who is not connected to the patient’s usual clinic.

“What that does is break down the relationship with the patient’s existing practitioner, and what we know is that if we don’t maintain a relationship with a practice or a GP, continuity of care is disrupted and clinical outcomes tend to be worse,” Pinskier says.

In a society where consumers now want everything instantly, he worries that some patients will opt for quick online consultations rather than seeing their GP for a comprehensive check-up. “It’s about the balance,” Pinskier says. “But [telehealth] does give GPs an additional tool in their armoury.”

Pinskier says shifting to digihealth could change many aspects of the profession, including service delivery, undergraduate and postgraduate training, the design of medical centres and the general management of triaging or screening patients.

“It may be that consulting rooms and practices of the future will look quite different. Do we really need to pay all this rent when I can just provide an internet connection and a laptop or an iPad? So, I think we’ll see significant change.”

Evolving healthcare model

A report from ANDHealth, a non-profit digital health accelerator, makes it clear that in the future, digital health technologies will be more widely used and accepted by the public and doctors, providing “a runway for increased take-up”.

Titled Digital Health: Creating a New Growth Industry for Australia, the report concludes that, to stimulate a thriving digital health industry, Australia’s healthcare industry and government should focus on four key areas – technology development, regulation, investment and implementation.

The biggest issue for early stage digital health companies, the report suggests, will be securing funding in a cash-strapped post-pandemic world.

To stimulate a thriving digital health industry, Australia's healthcare industry and government stakeholders should focus on four key areas - technology development, regulation, investment and implementation. Digital Health: Creating a New Growth Industry for Australia

Maxwell Plus is one highly regarded digital health company that is attracting investors and shaking up the treatment of prostate cancer.

The Brisbane-based company uses artificial intelligence (AI) and machine learning to make faster and cheaper diagnoses, while offering patients access to clinicians through a secure online portal.

“The portal allows them to get tested whether they live in inner-city Brisbane or out rurally, wherever they might be across the country,” says CEO Dr Elliot Smith, a biomedical engineer.

Smith says the company’s innovation gives men the early medical intervention required to ensure they have the best chance of survival, complementing AI with medical data from imaging, pathology, histology and genomics.

He believes other areas of medicine can potentially benefit from similar applications of technology.

Smith says he is driven by the desire to continue making medical advances and achieve business success.

“To have a company that’s literally out there saving lives and using advances in technology to help find something as important as cancer – to me it’s very, very exciting.”

Rural revolution

Rural and remote patients are getting rare access to the best medical specialists as hospitals, including St Vincent’s Hospital, Melbourne, fast-track the use of telehealth services.

Ian Broadway FCPA, the CFO at St Vincent’s Hospital, says referrals to the hospital’s specialist clinics are being supported via telehealth and phone consultation platforms amid prolonged social distancing restrictions in Melbourne.

“It’s telehealth ‘on steroids’ now,” Broadway says. “With COVID-19, it’s just become a necessity. And all of a sudden, remote patients have got the advantage of having specialist advice at their fingertips.”

In addition to allowing specialists’ skills to be used on a bigger scale, telehealth delivers efficiency and time-saving benefits for the hospital.

“If we had to send specialists to, say, Echuca [in northern Victoria], that would take up days of resources, whereas a lot of consultations can in the first instance be done remotely.”

"It's telehealth 'on steroids' now. With COVID-19, it's just become a necessity. And all of a sudden, remote patients have got the advantage of having specialist advice at their fingertips."

Broadway says the key to the ongoing success of telemedicine services is ensuring they are not just used to ramp up patient volumes for maximum financial gain.

With digital health, he believes there are greater opportunities to use data from My Health Record, the national digital health record system, so doctors can quickly access patient histories in emergencies. Robotic surgery, Broadway adds, is changing the face of treatments and presents “immense possibilities”.

Breaking the mould

In Malaysia, Azran Osman-Rani says the problem with traditional health treatment models is three-fold. First, there is an emphasis on “activities” such as counting calories and physical steps rather than “outcomes” such as weight loss and better cholesterol levels. Second, the focus is on transactional support via one-off consultations with a doctor, when multiple consultations are often required.

Third, healthcare has been very siloed, whereby a cardiologist checks a patient’s heart, for instance, and a dietitian monitors their food choices, but such specialists rarely, if ever, compare notes. “We’ve got to reimagine how we can deliver digital health that addresses these three things,” Osman-Rani says.

With Naluri’s efficient online coaching model, Osman-Rani says his team of medical specialists can assist 500 patients on an ongoing basis rather than being restricted to treating about 50 patients at a time in a one-on-one scenario.

“And by ten-folding the productivity, we can bring down the price of professional coaching by 10 times, which makes it much more accessible, particularly here in South-East Asia, where affordability is a big issue.”

As he contemplates the rise of this company and digital health in general, Osman-Rani hopes medical practitioners and providers, in tandem with start-ups such as Naluri, grasp the chance to become part of a continuous chain of treatment, not just a single cog acting independently.

“It’s about how you redefine your business model, and maybe COVID-19 is forcing all of us to rethink this question.”

Healthy outlook

The Asia-Pacific digital health market is estimated to reach US$105.7 billion (A$151.6 billion) by 2026.

The global telehealthcare segment is tipped to expand at 26.2 per cent CAGR from 2020 to 2026.

The hardware segment accounted for about 30 per cent of market share in 2019, and will grow in line with greater take-up of devices such as tablets, smartphones and wearables.

[Source: Global Market Insights]