Loading component...

At a glance

- Australian consumers paid A$23.9 billion in private health insurance premiums in 2017-2018, up by about 3.6 per cent from the previous year.

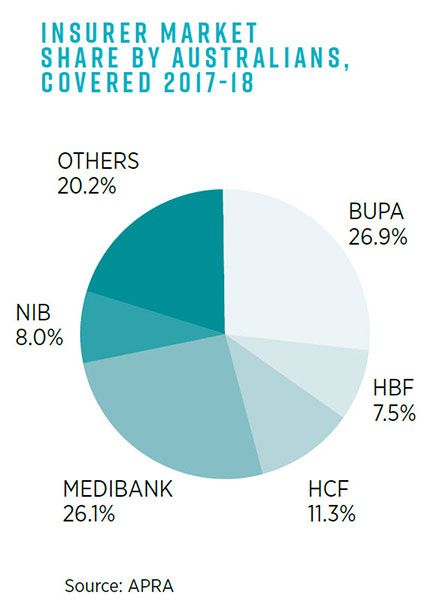

- Australia's private health insurance market comprises 37 insurers; however, 80 per cent of consumers are covered by just five – BUPA, Medibank, HCF, NIB and HBF.

- The greatest challenge for health insurers is the declining number of young people purchasing private cover due to affordability concerns.

- According to a policy blueprint from Private Healthcare Australia, restoring the government’s rebate to 30 per cent for those under 40 would increase young adult participation in private health care.

In terms of underlying health and wellness, Australia ranks among the top countries in the world.

A 2018 report from government statistics agency the Australian Institute of Health and Welfare found that, in overall health, Australia matches or outperforms many of the 35 member countries of the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD).

It has the fifth-highest life expectancy at birth for males and the eighth-highest for females, one of the lowest rates of smoking among people aged 15 and over, and the third-best rate of colon cancer survival.

Yet, when it comes to the financial state of the country’s healthcare system, the prognosis is far less upbeat. Faced with a sharp rise in chronic disease, an ageing population base, higher medical expectations by patients, increased technology and medical consumables expenses, and ongoing revenue volatility, Australia’s world-class hospitals and ancillary health support services are under severe stress on a costs level.

Louise O’Connor, executive director of the Epworth Eastern hospital, owned by Victoria’s largest not-for-profit private healthcare group, says the healthcare industry is facing a “tsunami of disruptors”.

“What we’re seeing now is a huge rise in issues, and the health system cannot sustain itself in this current format,” she told a CPA Australia healthcare forum in 2019.

“Something has to give.”

“It’s quite depressing when we know what needs to be done, but we’re hamstrung by political agendas, by the way the system is set up, federal versus state, some of the restrictions around our health insurance contracts, and patient treatments being episodic-based as opposed to wellness based.”

Health insurance under pressure

Adding to the broader financial strain is the continuing decline in the number of Australians holding private health insurance, with spiralling premium costs and out-of-pocket expenses spurring more people to drop their cover. That decline is directly impacting private hospital revenues.

Data from the Australian Prudential Regulation Authority (APRA), which oversees the insurance sector, shows that as of 30 June 2019, there were 11.2 million Australians, or 44.2 per cent of the population, that held private hospital treatment cover. This represented a decrease of about 28,500 people over the quarter, with the largest fall in coverage from people aged between 20 and 24.

Before the introduction of Medibank in 1975, about 80 per cent of Australians had private health insurance cover, but coverage levels fell sharply over the 1980s and most of the 1990s to about 30 per cent of the population. The introduction of a 30 per cent private health insurance rebate in 1999 saw coverage levels rise above 40 per cent.

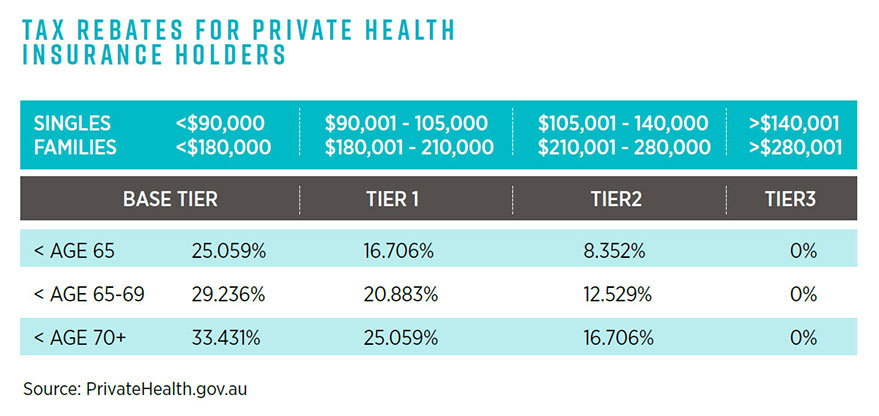

The federal government still subsidises those holding private health insurance through tax rebates on an income-tested basis, which is tiered for singles and families according to age.

The minimum rebate is 8.352 per cent for a single person aged under 65 earning A$105,001 to A$140,000 per annum, or a family earning A$210,001 to A$280,000. The maximum rebate is 33.413 per cent for a single aged over 70 earning less than A$90,000, or a family aged over 70 earning less than A$180,000.

The total cost of rebates to the federal government is about A$6 billion per year, but even with subsidies, many households are finding insurance premiums too high.

“People are increasingly feeling the pinch of private health premium increases and growing gap payments. In response, many are shifting to cheaper products with reduced coverage, and some are dropping their cover altogether,” according to Australian Competition and Consumer Commission (ACCC) deputy chair, Delia Rickard.

“The affordability of private health insurance has been an increasing concern for consumers in recent years.”

Premium rises vs wage growth

In a report to the Australian Senate, the ACCC noted that consumers paid about A$23.9 billion in private health insurance premiums in 2017-2018, an increase of almost A$834 million or 3.6 per cent from 2016-2017.

The amount of hospital benefits paid by health insurers was A$15.1 billion, and the amount of extras treatment benefits paid was A$5.2 billion.

“Cumulative premium increases have been higher than wage growth in the past five years, indicating that households with private health insurance are contributing an increasing proportion of their budgets to paying premiums,” the regulator said.

APRA data also shows there are 37 private health insurers in Australia, although nearly 80 per cent of consumers are covered by just five of them (BUPA, Medibank, HCF, NIB, and HBF).

Paul Lanza, Medibank group manager, hospital contracting, agrees the biggest challenge for health insurers, and the reason behind the declining number of people taking up private cover, is affordability.

“With young and healthy people not taking up private insurance, it’s keeping the older and sicker patients in the private health insurance system,” he told the CPA Australia healthcare forum.

“This pushes up the costs in the system. I think people aren’t seeing the value in private health insurance at the moment from an affordability perspective, because they’re paying for their insurance cover and also out-of-pocket costs.

“It’s easy to say we need to address out-of-pocket costs, but as a funder, how do you do that?”

Lanza says asking private hospitals to produce better patient outcomes and more efficiencies – with lower funding from private health insurers – is not a workable solution.

“We need to be looking at working collaboratively on new models of care that produce the same and better outcomes for patients, where people actually see the value in private health insurance.”

Avoiding a death spiral

In a 2019 report titled The history and purposes of private health insurance, the Grattan Institute said Australia’s private health system was in danger of entering a “death spiral”.

The Grattan Institute calculates that about 76 per cent of total private hospital income is derived from private health insurance premiums, with more than one-quarter (28 per cent) of private hospital income provided by the federal government’s private health insurance rebate to taxpayers.

“It’s inevitable that government will have to make tough decisions about whether more subsidies are the answer to the impending crisis,” say Stephen Duckett and Kristina Nemet of the Grattan Institute.

“Governments have failed to clearly define the role of private health insurance since Medicare was introduced in the 1980s. The upshot is we have a muddled healthcare system that is riddled with inconsistencies and perverse incentives.

“Australia needs to confront a fundamental question: what is the purpose of private hospital care?

“If its purpose is to complement Medicare, offering people a greater choice of specialists and a wider range of services, then the argument for taxpayer subsidies is weak, but if its purpose is to substitute for public hospital care, then the argument for subsidies is stronger.”

A policy blueprint released in October 2018 by Private Healthcare Australia, the private health insurance industry’s peak representative body, proposed that restoring the government’s rebate to 30 per cent for those aged under 40 would drive increased young adult participation and help maintain the balance between the private-public health systems.

Private Healthcare Australia said that in addition to the higher rebate, the government could, working alongside health funds, introduce a fringe benefits tax exemption applicable to private health insurance premiums for employees under the age of 40.

A third measure would be to increase awareness of existing private health insurance initiatives. These include the age-based discount introduced from 1 April 2019, whereby insurers have the option to offer people aged 18-29 years premium discounts of up to 10 per cent.

The total estimated cost of the industry’s suite of suggested reforms would be A$1.2 billion, although this would be offset by savings in the public hospitals system.

“Preliminary estimates, grounded in evidence from recent primary research, suggest that applying these three levers could restore participation in hospital cover in the 18-39 age group to 38 per cent by 2024, compared to a projected 32 per cent participation rate if no action was taken,” says chief executive, Dr Rachel David.

“This investment would not only drive increased young adult participation in private health insurance, but would also critically support the public hospital system and stabilise public hospital elective surgery.”

Gloria Sleaby FCPA, a director of not-for-profit community healthcare organisation DPV Health, says she has seen healthcare become more patient centred over time, regardless of whether it’s undertaken in the private or public systems. In the state of Victoria, the National Safety and Quality Health Service (NSQHS) Standards highlights increased focus on Partnering with Consumers, she says.

“It is more about what the patients’ needs and wants are, and patients are being encouraged to have a voice in their health care,” Sleaby says.

“People who are engaged in their health journey tend to have better outcomes.

“If they have better health outcomes, then all the hospitals should expect fewer return visits, all of which equates to cost savings.”

Improving consumer transparency

From 1 April 2019, the federal government introduced new rules to enable consumers to compare private health insurance offerings, requiring all insurers to standardise their coverage and classify their policies as either Gold, Silver, Bronze or Basic.

Private health insurers have until 1 April 2020 to comply with the new tiers, which must incorporate minimum standard categories of treatment.

Lanza says greater transparency is important, and points to Medibank initiatives on its website such as a procedure cost estimator, which enables consumers to look up a wide range of common surgical procedures to see their estimated out-of-pocket expenses after insurance and Medicare rebates.

Medibank has also added a hospital experience scores feature to its website so consumers can search individual private hospitals across Australia and see how they have been rated by “likelihood to recommend” and by “overall experience”.

“We’re trying to make that information more transparent for patients so they can compare,” Lanza says.

“Private health insurance is complicated. The private health insurance reforms that happened in April [2019] mean all covers are the same, but there is an alternative with the public system, and people just don’t see the value unless they use it, unlike house or car insurance.”