Loading component...

At a glance

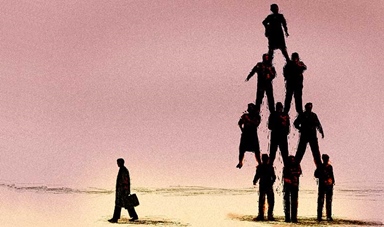

Accountants and other finance professionals are facing an increasing risk from clients who either don’t understand, or choose to ignore, their legal obligations under sharing and so-called “gig” economy businesses.

There are, however, opportunities for practitioners to advise new entrants to the sharing economy generally on the obligations of running a business and to ensure clients understand their hiring obligations.

Who works in the gig economy?

Both the gig and sharing economies use technology such as smartphone apps to connect clients with service providers or sellers. Examples abound, but well-known ones include Airbnb for accommodation, Uber for transport, Deliveroo for restaurant food delivery, and Airtasker for odd jobs.

Many workers in these new economies are independent contractors, a group which comprises about 9 per cent of the Australian workforce, or around one million workers, according to 2016 Australian Bureau of Statistics’ data.

Although the total workforce is roughly equally split between men and women, 72 per cent of independent contractors are male.

About 24 per cent are professionals and 55 per cent had more than one active contract in the week they were surveyed.

Critics say the gig economy is creating a new working poor of exploited employees, earning low wages without the rights that staff employees take for granted.

Lower wages and more competition do benefit consumers, however. A Grattan Institute report on the sharing economy estimates that ride-sharing businesses, for example, can cut more than A$500 million from Australian taxi bills.

The Grattan report says other sharing economy platforms are boosting employment and incomes for people on the fringe of the labour market and “putting thousands of underused homes and other assets to work”.

Gig economy risks to accountants

The informal nature of the gig economy carries a particular risk for accountants and other business advisors.

Regulators have made it clear they will pursue accountants and other advisers who facilitate breaches of workplace laws by their clients, with courts in the recent Ezy Accounting 123 Pty Ltd ("Ezy Accounting 123") and Kjoo Pty Ltd/Hanlim accounting firm cases fining accountants as accessories when their clients exploited workers. Ezy Accounting 123 is appealing.

Jonathan Mamaril, principal and director of NB Lawyers, says many workplace observers believe that legislation has not caught up with the changes wrought by more workers taking on gigs and entering the share economy.

He sees it affecting business consultants, ride-sharing drivers, IT workers, graphic designers and others in the creative industries who take on projects.

They may be covered by Australian Taxation Office definitions, workforce legislation in each state and the Fair Work Ombudsman, which all differ.

Sharing platforms also change. Uber, for example, can deactivate drivers over low ratings.

It might seem a small matter but Mamaril says it goes to the issue of control “and that goes to whether you have a contractor or an employment arrangement”. He adds, “This is going to come up more and more.”

He cites a 2013 Fair Work Commission case around termination of employment of a taxi driver, which found that although a driver can be an independent contractor for tax purposes, they can be an employee for unfair dismissal claims.

Mamaril says accountants and advisers should get advice from an employment lawyer or HR consultant if a client presents with a work arrangement that might be seen as sham contracting.

“They can say, ‘this is a grey area, there is potential liability for us, so we need to get confirmation or advice on this arrangement’.”

How accountants can help clients in the sharing economy

The fact that people are making money from hiring out private assets means some don’t consider it as taxable income.

The sometimes casual, and private, nature of gig economy work means some people may see the income as private and not taxable, or feel they are not earning enough to consider it as a business, or can earn income “under the radar”.

Shin Siang Yap CPA, CEO and partner at Malaysian firm YYC Advisors says some gig workers can struggle with record-keeping while others may decide to take the risk of not declaring income.

“Education is awareness and it’s important from the start to inform these clients of their responsibilities.”

She says accountants can explain obligations to clients and take them through the documentation and record-keeping on matters such as GST.

They can also warn of the risk of adjusted tax bills in later years, if income is not declared.

Malaysians like a “one stop shop” from their accountant and Yap says this has encouraged her firm to hold regular seminars to explain tax and regulatory issues to clients.

Benefits of the gig economy

This sector of the economy is also only expected to grow as entrepreneurs look for new opportunities and find innovative ways to earn income.

Yap has seen the launch of a home cooking service, where people are paid to visit private homes to cook a meal, as well as the service in reverse, matching homeowners with people who come to their home for a meal.

As the sector expands, accountants have a role in advising clients how to stay on the right side of the law.