Loading component...

At a glance

- Valuing a work of art that has no peer or which carries a high degree of cultural weight goes beyond analysing the state of the market, inflation and previous sales.

- To bring some consistency to the process, the Council of Australasian Museum Directors has developed a guidance framework for those managing the country’s museums.

- The framework’s authors recommend that unique objects of high significance and cultural sensitivity be regarded as “priceless” or “valueless”.

By Johanna Leggatt

One of the world’s most famous paintings, the Mona Lisa , also happens to be extremely hard to value, despite attempts by valuers and insurers to do so.

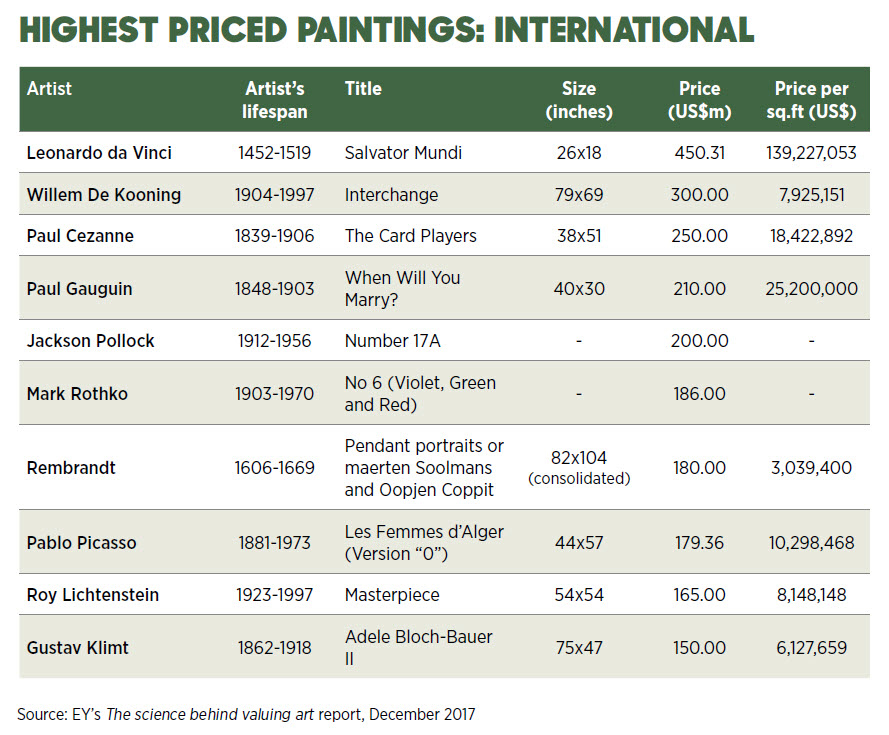

Leonardo da Vinci’s masterpiece was last assessed for insurance purposes in 1962, at US$100 million, which, according to Guinness World Records, is the highest insurance value ever for a painting. When adjusting for inflation, it is estimated that today it would be worth more than US$830 million.

Of course, determining a value for the painting is much more complicated than analysing previous sales, inflation and the state of the art market.

The Mona Lisa is impossible to replace, which cuts to the heart of the issue many accountants face when valuing precious works: how do you put a price on that which has no peer, and a high degree of cultural weight? How does financial reporting tackle this valuation challenge?

CFO of the National Museum of Australia, Ian Campbell, says museum pieces with an iconic status can be extremely problematic. These items are so valuable, paradoxically, they are almost impossible to value for financial reporting purposes.

“I don’t know how you value something that is a one-off, where there is nothing else in the world that could replicate this particular object,” he says.

“Of everything I do, this process of valuing heritage assets is the most variable, uncertain part.”

The issues in working out the value of art

As Campbell points out, heritage assets are not a homogenous group of items, but are incredibly varied, depending on the type of collection and the institution in which they are housed.

A museum is considerably different to an art gallery, for example, and exhibits are procured in many different ways.

“Some objects are donated, some are bought, so applying one criterion for valuation purposes is very difficult,” says Campbell.

“It’s very different, too, talking about objects you can move, for example, and a building.”

Renowned art collector and accountant Tom Lowenstein FCPA concedes that the area of art valuation is especially tricky, and one he prefers to steer clear of due to the problem of fakes.

“I look after the affairs of [artist] Charles Blackman [who died in 2018], and people will ring me up and say, ‘I have this particular work, it’s unsigned, can you get the OK on it?’.

“I say, ‘No, I can’t. I’m not an expert valuer’.”

Lowenstein notes that a number of firms are refusing to give a valuation or even authentication in the estates of famous artists because there are so many fakes in the marketplace, “and everyone is concerned with being sued”.

An object may be priceless because there are few people willing to value it, he says.

Ram Subramanian, CPA Australia policy adviser – reporting, policy and advocacy, says the definition of heritage assets can be broad, and goes much beyond museum artefacts.

“It’s important to note that heritage assets incorporate much more than museum pieces. Heritage assets can include buildings such as the Sydney Opera House and structures such as the Sydney Harbour Bridge,” he says.

“How you define a heritage asset and how you value it for financial reporting purposes are issues for accountants.”

Following a framework to value heritage assets

When a museum piece or artwork is sold on the open market, a benchmark value could perhaps be established, but an open market sale is not possible for many heritage assets, so open market value cannot be the only method of defining value.

“For example, there may also be some restrictions on selling an item for cultural or religious reasons,” Subramanian says.

“There are many pieces that people either can’t sell or won’t ever sell.”

To bring some consistency and direction to the issue of valuing heritage assets in museums, the Council of Australasian Museum Directors (CAMD) developed a national framework late in 2018 to guide those managing the nation’s museums.

This framework establishes a best practice methodology for the valuation of museum collections at their cost and, where cost is irrelevant (such as for bequests and non-financial methods of acquisition), notes they should be valued at “fair value”, which the Australian Accounting Standards Board (AASB) defines as “the price that would be received to sell an asset or paid to transfer a liability in an orderly transaction”.

The framework acknowledges that some items defy easy classification, and therefore valuation. Its authors refer, in particular, to “highly significant and sensitive collection assets ... those objects, which because of uniqueness, sensitivity or legal frameworks need to be regarded as priceless or valueless”. It recommends in these instances that the artefacts be recorded as having nil value.

It’s a conversation that is occurring on the international stage as well, with the International Public Sector Accounting Standards Board (IPSASB) undertaking a project to develop a standard that seeks to set out requirements to define,measure and recognise heritage assets in financial statements.

As part of this project, the IPSASB proposes floating the prospect of dividing heritage assets into operational (a building or office) and non-operational assets (paintings) for the benefit of financial reporting.

Subramanian says museums may take a number of approaches to determining the fair value of heritage assets: via analysing recent open market transactions; looking at the income-generating capacity of the asset, which could preclude those assets that are held in storage; and determining the replacement cost of the asset.

These criteria, as Subramanian points out, are important, but not the only criteria that need to be considered.

“Sometimes the very unit of measurement for fair value is hard to define,” he says.

“If the asset is the Sydney Harbour Bridge, then that is straightforward, but what if a museum has a collection of butterflies? Are we valuing each butterfly or all of them collectively?”

How institutions add value

CFO of the National Gallery of Australia (NGA), Kym Partington FCPA relies on a highly detailed valuation process to manage the more than 150,000 works of art within her orbit, which are valued at A$6 billion.

The national collection is represented by a diverse collection of ceramics, textiles, works on paper, oils, watercolours and drawings, and the NGA uses a sampling methodology for each category of art.

“We value 85 per cent of the collection based upon value, and extrapolate the results across the population,” says Partington.

“The valuer bases the estimation on current market comparisons and auction results. This is then discussed with the curators, who sometimes have a different point of view, particularly where a work of art is part of a series.”

What if a certain iconic artist’s painting achieves a stunning result at a Sotheby’s auction? Does that impact the value of the artist’s works held at the NGA?

“We don’t look at the results of a specific sale in isolation,” Partington says.

“It is unlikely that one large sale would be sufficient evidence of an overall shift in the fair value of a particular artist’s work.”

As Partington points out, certain individual pieces are just exceptionally rare, or perhaps the huge sale price has followed the death of the artist.

“There are many factors that need to be carefully considered before coming to a conclusion,” she says.

Partington admits that fakes, understandably, are a big concern.

“We have as part of our acquisition program a rigorous provenance governance framework,” she says.

“If we have doubts, we won’t buy it.”

Ian Campbell also uses a sampling methodology to value the collection at the National Museum of Australia every three years. “The collection is arranged into various sub-groups, and we have a list of high-value items, about 1 per cent, that are valued separately,” he says.

“Yet the majority of pieces are contained within large populations, and there is a sampling that is done that is then extrapolated over the entire population to give a value.”

If a piece is purchased via auction or direct negotiation, a valuer will advise how much the museum should pay.

Cultural value of heritage assets

Campbell notes that trying to value meaningful works through a financial lens can be problematic.

“Most collections in Australia are so large in value, compared to the rest of the operations,” he says.

“You have this collection that costs lots of money and far outweighs your other assets. It skews your financial statements and it can cloud how you’re performing as an organisation.”

When you’re a collecting institution, your job is to collect and to store pieces because of their cultural heft, says Campbell. In Australia, most collections were not even valued until the late 1990s, he points out.

Campbell relies heavily on valuers for financial reporting. However, he notes that substantiation requirements are growing more onerous, and the valuation landscape remains hugely subjective.

He believes that although the new valuation framework is instructive, heritage assets are impossible to shoehorn into neat categories for financial reporting purposes.

“We have had movements in valuations that have eventually come down to a person’s opinion,” he says.

“Should we be putting a value on these things? If you purchase them, then you have established a value, but where there is no value established, then it is much, much harder.”

Ways to value heritage assets

The AASB’s Fair Value Measurement Standard identifies three valuation techniques for fair valuing artworks.

Market approach: uses prices generated by market transactions for identical or similar assets to determine value.

Cost approach: this approach reflects the amount required to replace the service capacity of an asset.

Income approach: looks at the potential income-generating capacity of the asset by converting future amounts, such as cash flows or income and expenses, to a single, current value.