Loading component...

At a glance

Everyone who works in an organisation for any length of time learns the importance of pleasing the boss. Yet that attitude can result in a fear of speaking up – and when that fear comes to dominate an organisation, it can be poisonous.

This is the lesson revealed by a 2016 study of management experiences at Nokia, the mobile phone giant destroyed by the arrival of the iPhone and other touchscreen smartphones.

Study authors Timo Vuori, assistant professor in strategic management at Finland’s Aalto University, and Quy Huy, professor of strategic management at INSEAD in Singapore, propose that one major cause of Nokia’s fall was not complacency, software or technical inferiority, but collective fear.

Fear is a well-studied problem in the aviation and healthcare industries, where fatalities have occurred because junior staff felt too intimidated to challenge senior staff’s decisions.

Almost never, though, has such a high-profile corporation had its inside secrets and unspoken fears so comprehensively and publicly exposed as has the Nokia leadership.

Nokia’s slow rise and sudden fall

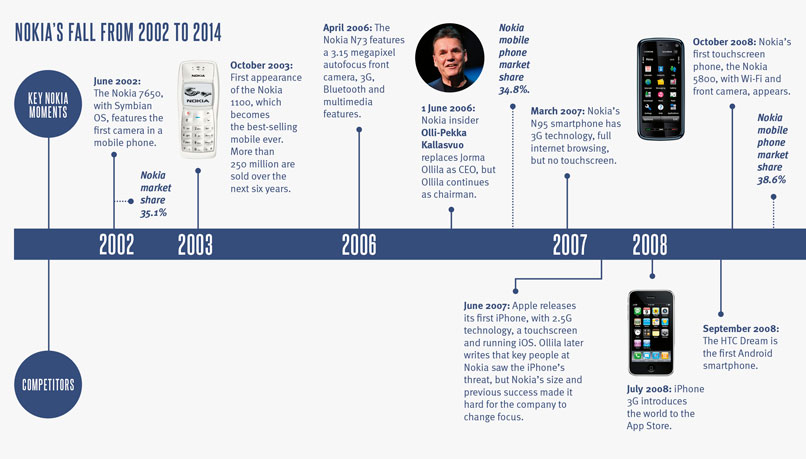

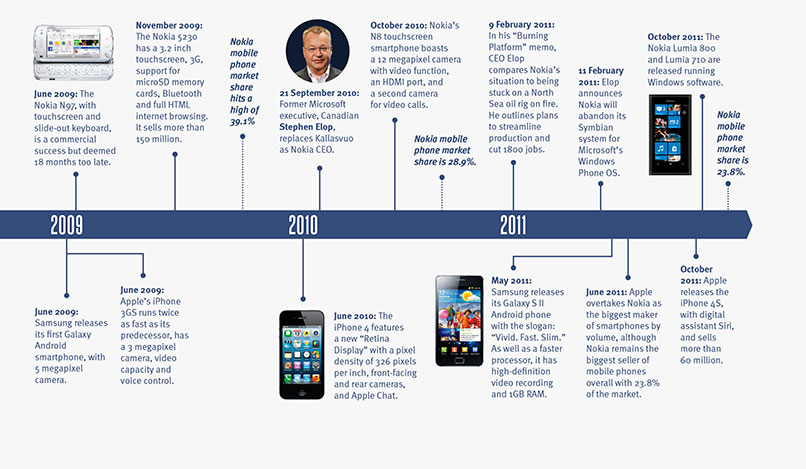

Finnish company Nokia transformed itself many times since it started as a timber company in 1865. Over time, it expanded to footwear, communication cabling, plastics, chemicals and military equipment, among other enterprises. Its most famous transformation to date made it the world’s leading mobile phone company in 1998, when it overtook Motorola.

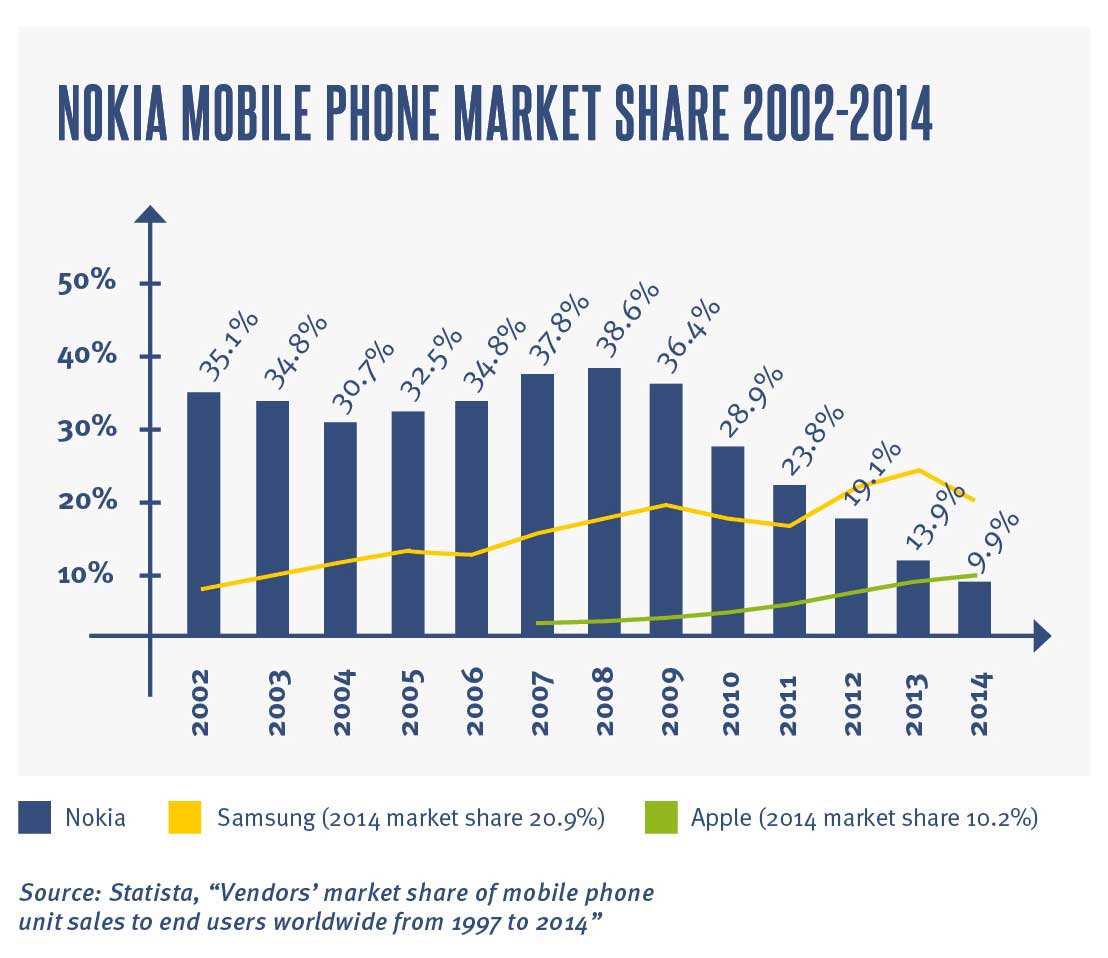

It dominated the mobile phone industry through the early and mid-2000s. At the end of 2007, almost 40 per cent of all mobile phones sold were Nokias.

In June 2007, however, Apple launched its expensive but dazzling iPhone. The iPhone combined basic communications functions with its iPod’s entertainment functions and the internet connectivity of the new third-generation (3G) telecommunications standard. All this was controlled by a new iOS operating system via a sleek, full-length glass touchscreen.

Nokia’s keypad-based hardware and externally developed Symbian operating system were no match. The company struggled to catch up as iPhone sales soared – 12 million in 2008, 20 million in 2009, 40 million in 2010.

To make matters worse, Google began licensing its Android system to Apple rivals in 2008. By mid 2010, despite significant efforts, Nokia had failed to introduce a model to match the iPhone.

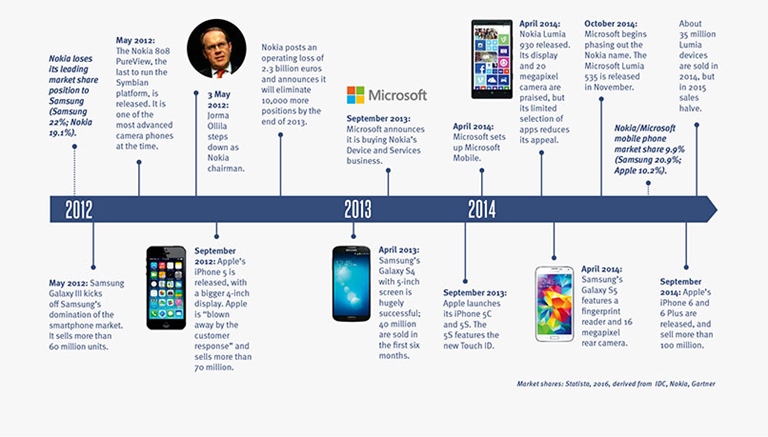

By June 2011, Nokia’s smartphone market share (although not its total mobile phone share) had dropped from 50 per cent to 15 per cent in less than four years. Two years later, it sold its phone business to Microsoft for about US$7.5 billion.

What just happened?

For Finland, the collapse of its global industrial champion was a sort of national humbling.

“The collapse of Nokia was such a big deal here in Finland, we really wanted to understand it better,” says Vuori.

Between November 2012 and February 2014 – a time when failure’s sting was being keenly felt – Vuori interviewed 76 of Nokia’s top managers (TMs), middle managers (MMs), engineers and external consultants. About half were past employees and the other half still worked at the company.

Vuori focused on unpacking the events between 2005 and 2010 that prevented Nokia from producing an iPhone competitor. Some interviewees were hostile, others receptive, but under the promise of anonymity, the Nokia employees laid bare what they had been unable to say or even understand at the time.

From their testimony emerges a picture of a company suffering from a broken relationship between its middle management and corporate leadership – a break that the researchers conclude ultimately undermined Nokia’s capacity to innovate.

Top managers were scared of losing their leading market position, so their fear was externally focused on competitors and shareholders. As one TM said, “Management is under huge pressure from investors … If you don’t hit your quarterly targets, you’re going to be a former [top manager] very fast.”

This led the TMs to exert pressure on middle management to develop innovative products rapidly, without fully revealing the severity of the external threats.

“The pressure we put on the software organisation was insane, because the commercial realities were so pressing,” said one TM. TMs admitted that they favoured MMs who provided reassuring reports, as well as “new blood” who displayed a “can-do” attitude.

That, in turn, generated an internally focused fear among MMs, who were mainly afraid of their superiors, as well as in other internal groups who were all jostling for resources and rank.

The aggressive behaviour of the “extremely temperamental” chairman and former CEO, Jorma Ollila, and in some of the TMs, further contributed to a fear of authority.

One strategy consultant remembered the chairman shouting at people “at the top of his lungs … in front of 15 other vice-presidents and senior vice-presidents”. Thus “it was very difficult to tell him things he didn’t want to hear”, surmised one HR consultant.

In this atmosphere, Nokia’s top management rarely heard any bad news about the limitations of the vital Symbian operating system or the slow progress in developing a more advanced software platform.

Perhaps most importantly, Nokia’s leadership did not hear enough about the unrealistic timeframes for new products. People who told the truth about the feasibility of schedules “put their reputations on the line” or risked being “labelled as a loser”.

One MM recalled “one meeting where they had an insanely optimistic deadline for one subproject that was critical for [the whole product] … I thought I should point it out, but the thought of challenging [top management] made my heart race, and then I just kept quiet.”

Management researchers call this potential moment of truth a “latent voice episode”. If employees think it will be futile to speak up, they won’t use their voice, says James Detert from the University of Virginia, who has been studying organisational silence for 15 years.

As one Nokia MM put it, “We needed a truth commission so people could tell [top management] things without the fear of punishment, to say what was really going on.”

The optimistic reports coming from middle management encouraged Nokia’s TMs to believe the company was progressing well in matching Apple’s iPhone, and the leadership pushed harder to catch up with Apple.

As MMs worked faster and faster, product quality declined. Nokia’s N97, for example, was released in 2009 to compete with the iPhone 3GS, but phone connections were weaker than in previous Nokia models, and many users struggled with Symbian’s touchscreen.

As Nokia strained to meet Apple’s challenge, top management became myopic, say the researchers. They put too much focus on new phone devices for short-term market demands, while neglecting their biggest long-term problem – an operating system that could match Apple’s iOS.

Thus Nokia lost its lead in the innovation race. A company held up as an exemplar of strategic agility was suddenly thrown into fear-based communication patterns that froze the flow of critical information from middle management to senior managers. In the end, fear stymied the most basic requirement for innovation – sharing information.

Vuori and Huy don’t claim that fear was the only factor at play, but they do say that it was an important one.

Fear is a common problem

The dynamics revealed in this research will not come as a surprise to seasoned corporate players; many have lived through similar experiences. Publishing the Nokia experiences, however, showed Vuori and Huy how widespread the problem might be.

“After the media published stories about the study, we were approached by people from about 10 different organisations in Finland, all sharing related stories from their own companies,” says Vuori.

That fear reduces workers’ effectiveness is not a new finding. While fear can motivate people to work harder short term, in the longer term it inhibits productivity, says British consultant Sheila Keegan in her 2015 book The Psychology of Fear in Organizations.

Nor is there any shortage of experts, past and present, who say that reducing fear is critical to enhancing productivity. In the 1950s and 1960s, management consultant W. Edwards Deming developed his 14-point philosophy for transforming business performance. Principle number eight is “drive out fear”.

Concern about offending those higher up the workplace hierarchy is both natural and widespread, but it isn’t easy to eliminate when bosses control people’s income and social standing.

Leaders should therefore expect that they are not going to get from their staff the quality information they need to make good decisions, says leadership consultant Jen St Clair.

“The power differential is just too strong for staff to challenge their boss, so leaders need to decide what they are going to do to mitigate that,” says St Clair, who spent 10 years in the Australian Public Service working in executive roles and now facilitates peer-based learning for senior executives.

Transforming a fear-based culture

Certain fields where excessive deference to authority can be dangerous – notably aviation and healthcare – have developed policies and communication tools to help junior staff speak up. In business more generally, leaders can use tools to help ensure they get the intelligence they need.

St Clair recommends the “manager once removed” approach, where a manager initiates regular one-to-one meetings between her staff and her own boss, encouraging staff to talk about anything of concern.

“This works best when the process is institutionalised and goes all the way up the hierarchy,” she says.

Transforming a fear-based culture is hard work, but it is possible, says Sydney-based executive coach and organisational culture consultant Erik de Jong, who regularly assesses the level of fear in multinational organisations as part of his cultural diagnostic work.

A leader who is willing and able to listen to the fears of his or her workers is essential to this transformation, says de Jong.

“If fear can be safely named and heard, it loses its power, but unnamed it goes underground and continues to do damage.”

Return of the Nokia mobile

Nokia’s sale to Microsoft included a pledge not to re-enter the phone market before 2017. That time is up, and Nokia fans expect two models of Nokia-branded Android phones will be unveiled at the World Mobile Congress in Barcelona this month.

Made by Finland-based company HMD Global, which is headed by former Nokia and Microsoft executive Arto Nummela, these new phones may well signal a rebirth of the Nokia mobile. It will be a chance for another Finnish company to learn from the Nokia experience – and perhaps deal better with fear.

What went wrong?

Nokia’s exit from the mobile phone industry has attracted various explanations from management theorists:

- Nokia was too complacent. Vuori and Huy, however, depict a company desperate to respond to Apple.

- Nokia didn’t see the radical innovations coming. In reality, the company had developed touchscreen technology but failed to make it work smoothly and powerfully.

- Nokia needed to service a huge customer base, which it did at the expense of innovation.

- Nokia struggled to remain agile, as it had a market-leading position to protect.

- Nokia became too controlling and bureaucratic, as a result of its organisational structure and leadership.

- Nokia was catering to so many market segments with different phone models that it lacked focus.

Joshua Gans, author of The Disruption Dilemma and professor of strategic management at the University of Toronto, says it’s likely almost nothing could have saved Nokia.

“People like to point the finger at all those factors, but the fact is they were doomed – they had their time and that was it. It took Nokia years to understand that they were now actually in the business of selling computers, and that they needed a new operating system for their smartphones to be competitive. By then it was too late. Someone starting from scratch, who was not invested in protecting their status, would have had a much better chance.”

Stephen Elop, Nokia’s CEO between 2010 and 2013, found the entire experience perplexing. “We didn’t do anything wrong, but somehow, we lost,” he declared when announcing the sale of Nokia’s phone division to Microsoft.

“Distributed Attention and Shared Emotions in the Innovation Process: How Nokia Lost the Smartphone Battle”, by Timo O. Vuori and Quy N. Huy; Administrative Science Quarterly, 2016, Vol. 61(1) pp9–51.