Loading component...

At a glance

Of all the scams in a fraudster’s toolbox, phishing is the most common.

Phishing is an attempt to obtain sensitive information, such as usernames, passwords, credit card details or even money, often by sending an email that looks as if it is from a legitimate company but with a link that takes the unsuspecting victim to a fake website that is disguised as a real one.

In particular, attacks via email are increasingly sophisticated, cunning and difficult to detect, which is why about one in four people click on them.

Recipients of these emails risk disclosing confidential information about themselves or their firms and falling victim to computer viruses, trojans, keyloggers and ransomware.

MailGuard CEO and founder and author of the book Surviving the Rise of Cybercrime, Craig McDonald, believes the incidence of successful attacks in Australia is higher than the global average.

Australians, he says, can be just too trusting for their own good, having grown up knowing only a relatively limited number of brands.

“When we see an email from one of those in our inbox we’re quite happy to click on it, whereas in the US for example there are so many different brands, the likelihood of dealing with all of them is fairly remote,” he says.

“Even if you’re a CommBank customer and receive an email from NAB, there’s still a 20 per cent chance you’re going to click on it.”

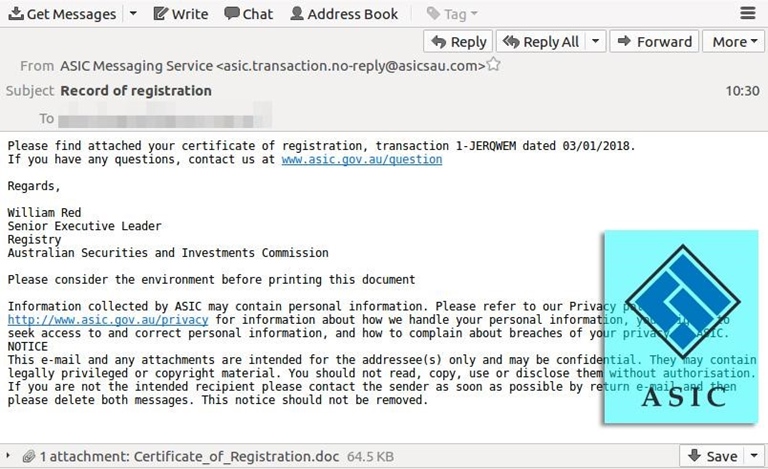

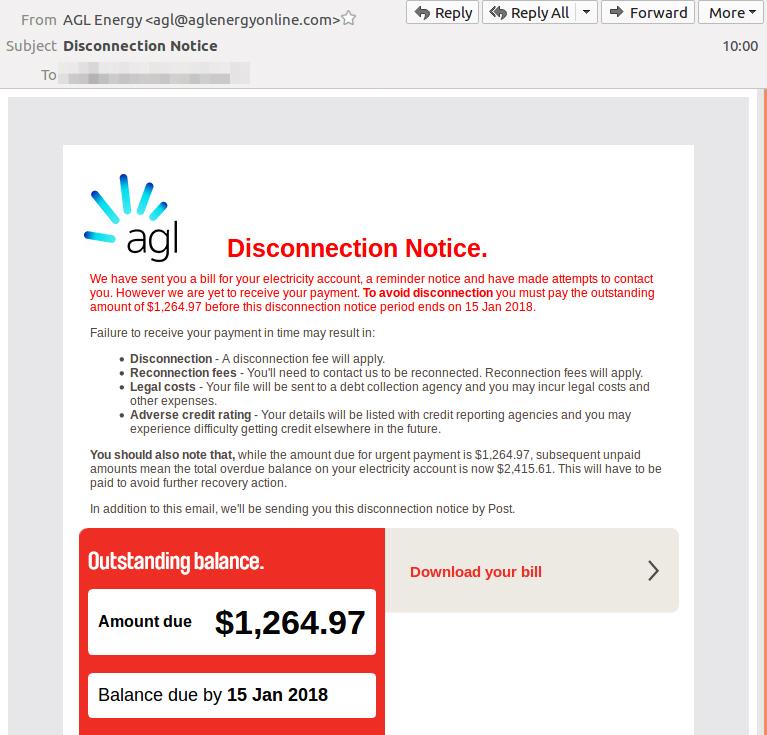

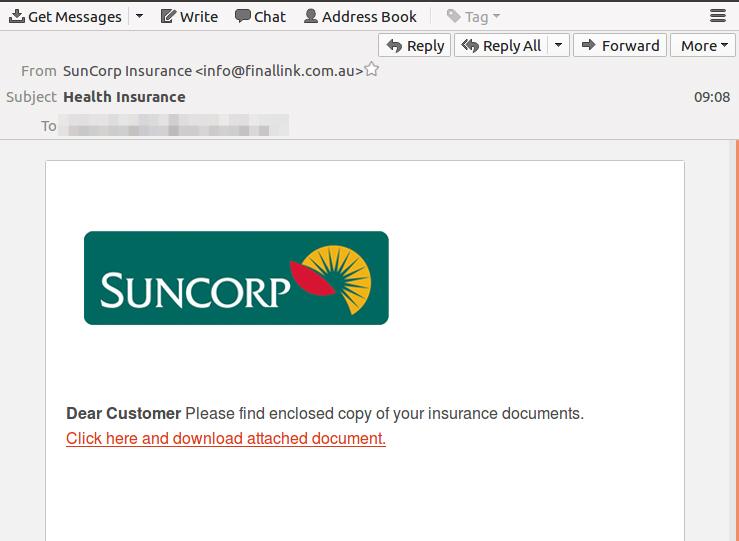

Indeed, customers of numerous household names such as the Commonwealth Bank, AGL, Origin Energy, Suncorp, Ticketek and Australia Post have all been targeted by cybercriminals, along with corporate watchdog ASIC. During peak periods the ATO has received more than 750 scam reports a day.

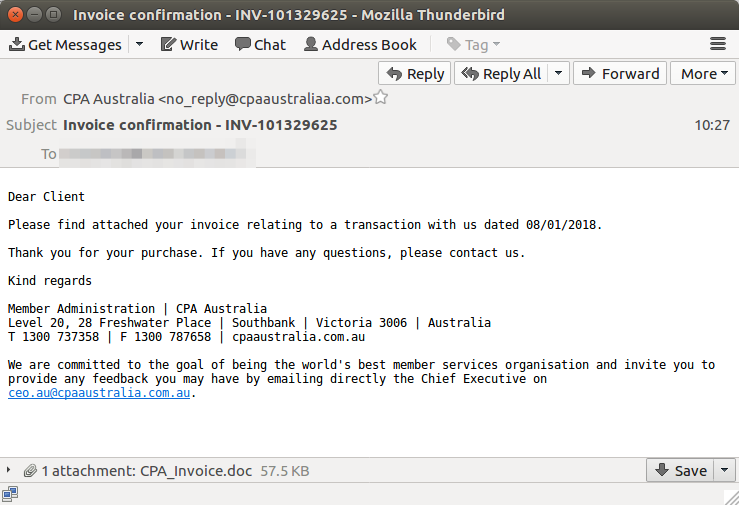

In a “brandjacking” attack in January 2018, an email phishing scam posed as an invoice from CPA Australia. The email included a Microsoft Word .doc file “invoice” attachment which contained malicious macros. If downloaded and opened, it would activate a trojan or similar malware and hijack the recipient’s computer system, gaining access to personal files and data.

Scammers up the ante with better phishing bait

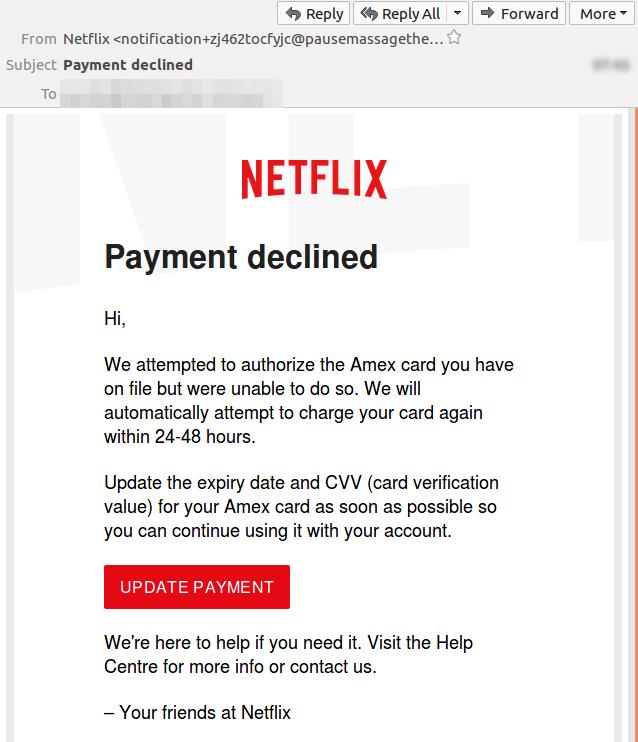

It used to be that phishing emails were conspicuous through spelling mistakes, bad grammar and obvious trickery (you won a lottery you never entered!). However, most cybercriminals now take great care to camouflage their bait: many fraudulent emails contain privacy warnings, the company name and email address, original logos and other content to make them appear authentic and generate click-through legitimate marketers would envy.

“Cybercriminals are the best marketers in the world because they get to use everyone else’s brands,” McDonald says.

“There was a study in 2015 that cited a 270 per cent increase in cybercrime, but I think it’s 1000 per cent or more because nine out of 10 businesses are now receiving unwanted or criminal intent emails.”

What the FBI calls business email compromise (BEC) scams, around a quarter of which target Australia, have led to staggering losses – in excess of US$5.3 billion at last count. So-called CEO fraud – or whaling – where someone in an organisation is sent an email with a spoofed sender address that appears to come from the CEO, CFO or other top executive saying that funds need to be immediately transferred to an outside account, is growing exponentially.

“We’ve all got something the criminals want, and that’s money”, McDonald says. The problem is how to combat them.

When it comes to phishing, old fail-safes aren’t enough

Cybersecurity experts have long recommended a variety of protective measures. These include:

- training and educating employees

- installing an anti-phishing toolbox on your web browser

- installing browser security patches and updates as soon as they are released

- using a popup blocker

- using a firewall

- keeping anti-virus software updated to the latest versions

- making sure a site’s URL begins with https rather than the much less secure http

- checking its security certificate by clicking on the padlock icon in the address bar

- hovering the cursor over links to reveal the actual address.

However, whaling attacks now commonly come in plain text emails that evade most anti-virus security platforms. As McDonald notes, the criminals behind them are well organised and multi-layered, with workhorses trawling the likes of Twitter and Facebook for detail that will add an extra element of social engineering to the mix.

A malicious text email or SMS will invariably be just a few words, but if it also wishes you a happy birthday or asks how the party went on the weekend, it has a good chance of appearing legitimate.

Further, there are now so many customer relationship and content management systems used for sending third-party messages that hovering the cursor over a hyperlink is next to useless, as no matter who you add to a “safe list”, providers can change daily.

“Criminals are bypassing anti-virus software quite easily, even to the point of hovering over images which… actually reference back to the originating site,” McDonald says.

Trust but verify

With scattergun phishing scams intended to dupe all and sundry, spear phishing targeting specific individuals and whaling doubling down by setting sights on CEOs and others in the C-suite, McDonald says everyone – hard as it may be – needs to pause for a moment and think, why did I receive this? Why do I owe this? Why am I being subpoenaed via email (you can’t)? Why are Australian Federal Police emailing me a traffic infringement notice (they don’t)? Why is my Netflix account being suspended until I update my credit card details (it isn’t)?

Do a basic check no matter how compelling or threatening the message.

“Phone the utility or bank or log on to your own account directly as opposed to going via the email communication,” McDonald warns.

“Curiosity is a killer and because a lot of attacks are immediate, there’s no second chance once you click on something, which is exactly what the criminals want.”

Implement a multi-layered defence against phishing scams

Prevention is still the best strategy for organisations when it comes to dealing with cybercrime. McDonald recommends a multi-layered defence aimed at stopping fraudulent emails in their tracks through specialist advanced cloud security solutions and constant due diligence in the event certain types of messages do get through.

“There have to be internal processes around validating [internal and external] requests,” he says.

“Authentication doesn’t need to be automated, but it does need to be thought through. It could be as simple as verifying that an SMS came from the CEO’s mobile number, referring to the CFO, checking a provider’s bank details against what is logged in the accounting system, or delaying a payment until it can be ratified by the CEO.”

Despite this, McDonald says it is not uncommon for million dollar transfers to be made without question, then to realise it was CEO fraud – in which case the money is gone and won’t be back.