Loading component...

At a glance

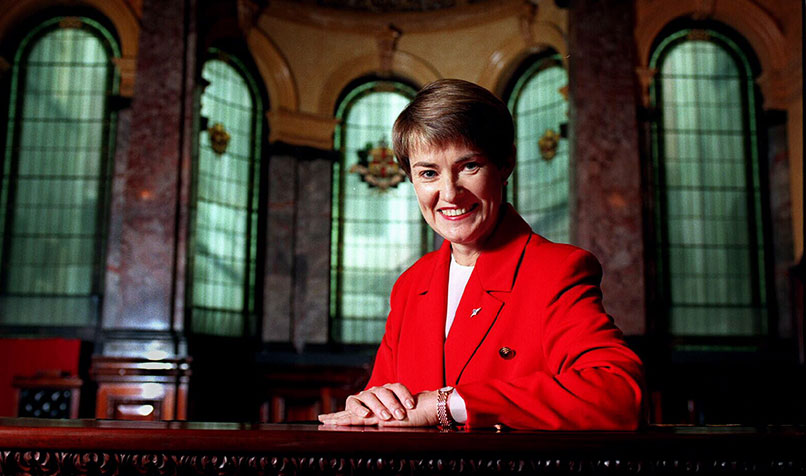

- Elizabeth Proust is one of Australia’s most successful and influential business figures.

- She began her career in public affairs at BP, but moved between the public and private sectors in a series of senior roles over many decades.

- She has served on for-profit and not-for-profit boards, including the Truth, Justice and Healing Council.

- Proust advocates for greater numbers of women on boards and argues women need to network to ensure their work is recognised.

By Johanna Leggatt

As one of Australia’s leading business figures, helming departments within both private and public institutions over the past three decades, Elizabeth Proust has spent much of her career advancing up the corporate rungs in the company of men.

“Given my age, all my career mentors have been men, including (former Victorian Premier) John Cain and Chris Larcombe, whom I worked with at BP,” she says.

Yet Proust’s seminal career influence was not the directors in the male-dominated boardrooms and departmental heads with whom she lunched, negotiated and worked alongside, although there were many whom she admired.

Instead, the person she credits most with driving her career forward has been her mother.

“She made great sacrifices for our education and pushed her daughters, in particular, to get the best education we could,” Proust says.

“It was always expected that my siblings and I would all go to university, and part of that expectation from my mother came because she was denied the opportunity to go to university, largely by her father.”

Proust’s mother came of age in the 1940s, and as far as her father was concerned, at that time women got married, had babies and dedicated themselves to their families.

“Mum’s disappointment at not being able to pursue her own career was a big driver for what I went on to do,” Proust says.

However, Proust, who is one of nine children, was never going to do things exactly by the book.

Born in Sydney and educated in Wagga Wagga, Orange, Balmain and Wollongong, she volunteered with the Young Catholic Students movement in Melbourne after leaving school. It was akin to a “gap year”, as Proust puts it, and it is here where she met her husband, Brian Lawrence.

Much to her mother’s chagrin, Proust and Lawrence’s union was quickly formalised.

“I announced our engagement at my 21st birthday and then we had our daughter, Katrina, when I was 22, and I think my mother was horrified,” Proust says.

“I think she worried that that was all I was going to do, but then she became proud later on when I got both my degrees and went on to take up various positions.”

“Various positions” understates Proust’s trail-blazing career path through Melbourne in the 1980s and 1990s: an astonishing succession of roles and appointments, followed by titles and tributes, including Officer of the Order of Australia in 2010 for distinguished service.

Elizabeth Proust: In the boardroom

Proust is a Fellow of the Australian Institute of Company Directors (AICD). She was the chair of the AICD until November 2018, and is currently chair of the Bank of Melbourne and Nestlé Australia, and a non-executive director of Lendlease.

She is a former director of Perpetual, Spotless, Insurance Manufacturers Australia, and Sinclair Knight Merz Holdings.

Yet, perhaps incongruously, Proust’s path to the boardrooms of Australia’s biggest companies started with an arts degree at Sydney University, where she studied government, psychology, anthropology and English.

After she married, Proust moved to Melbourne and transferred to a BA (Hons) at La Trobe University.

“I then studied a law degree part-time, as finances permitted, and my employer, BP Australia, was very encouraging of that path.”

After working in public affairs at BP, she took on a role as secretary of the Victorian Attorney-General’s Department and secretary of the Department of Premier and Cabinet.

Proust went on to work as chief of staff for former Premier John Cain and was head of the Department of Premier and Cabinet during the Kennett government, before taking on the role as CEO of the City of Melbourne – a tough gig, but one that she looks back on fondly.

“The City of Melbourne job was a great example of listening to my heart rather than my head, as everyone said it [the bureaucracy] was too broken and not worth the effort,” she says.

“After five years [as CEO], I could see the tangible differences that the team that I led had made to the life of the city, as well as to its finances.

“That’s much more meaningful than some of my other accomplishments.”

Proust also spent eight years with the ANZ Group, including four years as managing director of finance arm Esanda.

What distinguishes Proust’s career from those of her contemporaries has been her fluid – and highly unusual – transition between the private and the public sectors.

“There isn’t enough movement, generally speaking, between the public and the private sectors in Australia,” Proust says.

“Part of my success, I think, was that I was able to move between the public and private sectors, and while this happens in the US a lot, in Australia, people think that they still have to choose between the two. They don’t.”

The public sector was at the forefront of diversity at the time and often very good at promoting women, Proust notes.

Working in the public and private sectors

Proust, however, equally enjoyed the cut and thrust of the private sector, which allowed her to learn new ways of managing people.

“The private sector was the leader when it came to thinking about how to motivate people, and it was very cutting edge in this regard,” she says.

Proust’s husband is a retired industrial barrister, and while she never worked in the legal profession, her legal training became integral to her work.

“I never gave myself legal advice, but I could hold my own in the Victorian Attorney-General’s Department and with the chief judge when discussing computerising the courts, for example,” she says.

“That legal background gave me the ability, too, to be really objective.”

By 2006, Proust was a full-time non-executive director for both listed, government, for-profit and not-for-profit organisations.

"While much has been achieved, too many boards in the ASX200 have stopped at appointing just one woman."

Once again, the variety of the work enthralled and motivated her, but she maintained a special passion for her not-for-profit work, deeply rooted in her Catholic upbringing.

She has chaired the Melbourne Symphony Orchestra, was chairman of the Centre for Dialogue at La Trobe University and was also a director of Nonprofit Australia.

“I’ve learned a great deal from each organisation, especially about the people who work in them, their motivations and their ideals,” she says.

“I think that serving on one is an important part of giving back to the community.”

Proust’s most recent role in the not-for-profit sector was sitting on the Truth, Justice and Healing Council, which coordinated the Catholic Church’s response to the Royal Commission into Institutional Responses to Child Sexual Abuse.

“I joined the council because I was appalled by what the church I was brought up in had done to vulnerable children and adults,” she says.

“The time spent on the council was both some of the best and worst experiences of my life: the best because of the people around the council, on the Royal Commission and elsewhere who were working hard to reduce the impact of the harm, without ever diminishing the culpability of those responsible, and the worst because it totally undermined my faith in the church I had spent my life in.”

As of late last year, Proust no longer sits on the council (which has largely concluded its work), nor any other not-for-profit boards, and has been clearly affected by what she heard.

“Serving on the Truth, Justice and Healing Council was a searing time and I have no confidence in the so-called leaders of the Catholic Church in Australia to make any difference to the underlying culture that was a large part of the sexual abuse that occurred,” she says, before adding that there is very little more she is willing to say on the matter.

“Until women have an equal role in church leadership, little, if anything, will change.”

Promoting women in leadership

Proust's abiding passion is promoting women into leadership roles.

According to the Australian Institute of Company Directors (AICD), women make up only 29.7 per cent of the boards of Australia’s largest 200 listed companies, with a total of four boards in the ASX200 comprised entirely of men.

“We seem to have stalled at just under 30 per cent,” Proust says. “While much has been achieved, too many boards in the ASX200 have stopped at appointing just one woman.”

While there are plenty of women available and qualified for board roles, not all of them have the sponsorship or networks necessary to achieve appointment, she notes.

Furthermore, some women lack the requisite financial skills and background.

The AICD runs an annual Chair’s Mentoring Program for women, which accepts dozens of women per year.

According to Proust, hundreds of women apply for it annually, but she and the other selectors have had trouble finding mentees who are adequately qualified.

“Essentially, it was a struggle to find candidates with sufficient financial literacy, candidates who could display adequate knowledge of a balance sheet, of budgeting, of P&L [profit and loss],” she says. “Women do often have a deficit in this area.”

She believes workplace inequality, self-imposed limitations and the harsh reality of juggling family and a high-powered career are most likely to blame.

“Women are busy having careers, as well as juggling family and children, and this makes it difficult to skill up in additional areas,” she says.

Boards are getting smaller as well, and are now demanding people with a range of outstanding and diverse skills.

"There isn't enough movement generally speaking, between the public and private sectors in Australia."

“Women tend to work in areas such as HR, marketing, law and strategy and they are not becoming the CFOs, and too many haven’t studied commerce or finance,” she says.

“Women need to make sure that they acquire financial experience, including managing P&L, and leadership.”

Most importantly, women need to get better at networking, something that Proust struggled with in the early days of her career.

“As someone who is somewhat of an introvert, and prefers her own company and a good book, I had to learn how to speak in public and in front of a lot of people,” she says.

“A lot of women believe that if they work hard and put their head down, they will get ahead. While I wish that were the case, you do need to make sure your work is recognised.”

While women need to network, that doesn’t necessarily mean drinking with colleagues after work instead of going home.

“It does mean taking part in work functions, such as CPA events, to develop networks,” Proust says.

The same principles apply for men who aspire towards becoming directors.

“I don’t think for a moment that directors need to be legally trained, but they do need to understand the law,” she says.

“They need to understand finance. This doesn’t mean they need to be a CFO or an audit partner, but every director must understand the accounts and be able to ask intelligent questions of the CFO. It also helps, too, if you know when to speak your mind and when to listen.”

Proust has long maintained an active interest in good corporate governance, but acknowledges community expectations of what is achievable, post the (Hayne) Royal Commission into Misconduct in the Banking, Superannuation and Financial Services Industry, may be unrealistic.

“I think that the community does not understand the difference between non-executive directors and executives,” she says.

“The worry in the post-Hayne world is that there is an expectation that directors will stop all bad things from happening.

“The best risk management, and the best directors, can’t achieve this, but they can be diligent and hold management to account, and of course themselves to account, when things go wrong.”

Proust’s career path has been anything but conventional; however, with its moves between private and government sectors, it shows there are different ways to serve at a high level. There are different ways to reach the top, and Proust will be encouraging more women to pursue them.

CPA Library resource:

My other life

“There is my family, including two grandsons in Sydney, and following Collingwood [Australian Football League], as a weekly dose of footy keeps me sane even if the Pies can drive me to distraction on many occasions. I also enjoy concerts, galleries, travel, and reading. Life outside of work is more important than work itself. I’ve always enjoyed my work, but it’s always been a means to an end, not an end in itself.”

Three skills I draw on every day

Listening, maintaining a sense of humour, patience.

Books that inspire me

“I have to say I read history, biographies and fiction, rather than books on careers or business. I find most of them too clichéd and not worth spending my time on. A notable exception, recently, is Marianne Broadbent’s The Agile Executive, which is both thoughtful and practical.