Loading component...

At a glance

One of Australia’s earliest accountants remains one of the country’s greatest historical figures.

John Macarthur arrived in Sydney in 1790, a military officer determined to prosper in the new colony.

Macarthur and his wife Elizabeth are famous for introducing merino sheep to Australia and he is cited as the father of the Australian wool industry, but it was Macarthur’s accounting skills that set him on his way.

As one of the few people who knew how to prepare a statement of account, he gained insights into trends and the growth of commerce in the new colony.

People such as Macarthur and John Palmer, who ran the government store, had enormous power in the absence of banks and were able to encourage farming and economic enterprise to meet the needs of the growing colony.

The reports sent back to Britain by the early accountants – Macarthur was paymaster of the NSW military corps – also showed British investors that money could be made in Australia, starting a long tradition of foreign investment.

Accounting education in Australia

Australia’s first schools taught accounting, with a school in Sydney opening in 1805 offering child pupils tuition in reading, writing, arithmetic and bookkeeping “according to the Italian mode” (double entry bookkeeping).

Sir Alexander Fitzgerald was a pioneer in accounting education and was described as “the outstanding figure of his time in Australian accounting”.

Born in 1890, he entered the workforce as a clerk for a hardware merchant, but studied accounting and worked his up way up in the profession.

When the University of Melbourne introduced a commerce degree in 1925, he enrolled as a foundation student while also taking a job as an assistant lecturer in accounting.

A long academic career followed.

Fitzgerald wrote and edited accountancy texts and served on company boards. His involvement in many government inquiries and a royal commission led to improvements in government financial reporting at state and federal level.

Accounting controversy

Many accountants spoke out against government policy during the 1920s and 1930s.

F W Spry, President of the Victorian division of the Commonwealth Institute of Accountants, a forerunner of CPA Australia, warned in 1925 that business owners had become extravagant due to wartime financing and many did not have adequate working capital as a result. Everyone had to make better use of their resources, he said.

Speeches made by the profession’s leaders were widely reported in the press of the time and stirred public debate.

“Accountants, then, were actively examining and commenting on the overall picture of the Australian economy. They were unafraid of warning the community and governments of the problems which they saw,” says Rob Linn in his 1996 book Power, Progress and Profit, A history of the Australian Accounting Profession.

At the first Australasian Congress on Accounting in 1936, several speakers criticised government finance policy.

Congress president Sir George Allard was cheered when he condemned the 75 per cent rise in government debt since 1919.

A E Barton gave a paper accusing successive governments of manipulating public accounts by delaying revenue collection and postponing payments.

Pioneer women accountants

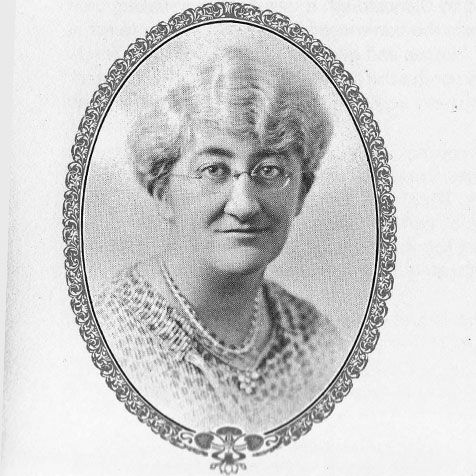

In 1915 Mary Addison Hamilton was the first woman appointed to a professional accounting body anywhere in the Commonwealth, when the Institute of Accountants and Auditors of Western Australia, a precursor of CPA Australia, admitted her as a member.

An outstanding student, she topped Fremantle Chamber of Commerce examinations and studied accountancy at night school.

Hamilton broke down the barriers to be recognised as a professional at a time when women were refused entry to many professional associations.

She worked as a clerk for the WA Education Department but volunteered accountancy services as treasurer or auditor to many not-for-profit groups, including the Royal Lifesaving Society and Catholic Women’s League.

Barbara Pimlott was typical of many young people whose accountancy career was their escape from poverty. Her father’s building business was hit hard by the 1930s Depression and the family had a difficult time.

Parents often encouraged their children to study bookkeeping and commercial subjects in the hope it would lead to a steady job in a bank or office, or because they could not afford study in law or medicine.

Many of these young people then decided to study accountancy after work to improve their prospects.

Women such as Pimlott got their break when men joined the forces in World War II and large numbers of young women moved into commercial accounting.

Their contribution was vital to maintaining businesses during the war and they changed attitudes so that in the 1950s and 1960s women were encouraged to consider accounting as a career.

Accountants in politics

Sir Arthur Fadden left school aged 15 to work as a billy boy making tea for sugar cane cutters, studied accountancy through a correspondence course, and went on to become prime minister.

Sir Arthur, known as Artie, was a public practitioner in Queensland before entering Federal Parliament as a member of the Country Party in 1936, and was appointed treasurer in 1940, directing the country’s finances through wartime.

He became prime minister in 1941 but his government only lasted 40 days, falling victim to political infighting.

In 1949 a Liberal-Country Party coalition won government with Sir Robert Menzies as prime minister and Fadden as his deputy and treasurer.

Fadden brought down a record 11 budgets, including the “horror budget” of 1951-52 which raised taxes to attack inflation.

After the budget’s poor reception he said, “I could have had a meeting of all my friends and supporters in a one-man telephone booth.”

In the 1950s he pushed through legislation that founded the Reserve Bank of Australia and he created the Commonwealth Development Bank to meet a lack of long-term borrowing finance for farm development and small industries.

Today’s politicians can look on in envy at Fadden’s ability to push through major economic reforms during a long period in government, but he was continuing a tradition of accountants who used their expertise to argue for reforms that would benefit the economy and the nation.

Sources:

Power, Progress and Profit, A history of the Australian Accounting Profession by Rob Linn, published by the then Australian Society of CPAs, 1996.

Australian Dictionary of Biography.

The Argus Newspaper reports of the 1936 Congress held by the National Library of Australia.

Cooper, K. and Kurtovic, A, Mary Addison Hamilton, Australia’s First Lady of numbers, School of Accounting & Finance, University of Wollongong, Working Paper 19, 2006.