Loading component...

At a glance

In 2017, the Nobel Prize in Economic Sciences was awarded to American academic Richard Thaler. This brought the world’s attention to a drawing of a housefly, urinals and an airport cleaning manager.

This unlikely combination illustrates Thaler’s “nudge theory”, which has helped governments and organisations across the globe apply behavioural insights (BI) to understand human decision-making and design effective public policy.

BI aims to understand and influence behavioural change among people by simplifying processes, removing unnecessary steps and making services easier to use.

BI is not a single concept, but an umbrella term that applies to research into behavioural economics, the sciences and psychology.

Thaler and his co-author Cass R. Sunstein coined the term “nudge theory” in their 2008 book Nudge: Improving Decisions About Health, Wealth and Happiness.

Thaler says the “urinal fly” is his favourite example of all the practical applications of behavioural economics.

The story came to public attention in the 1990s. In an effort to reduce the cleaning needed in the men’s toilets at Schiphol Airport in Amsterdam, the cleaning manager had the genius idea to put small, fly-shaped stickers at the bottom of the urinals.

It seemed that, when faced with the opportunity to aim at something, many men did just that – subconsciously or otherwise.

It also meant there was 80 per cent less spillage, which led to an 8 per cent decrease in cleaning costs.

Nudge theory argues that positive reinforcement and indirect suggestions that encourage compliance can influence decision-making at least as effectively as direct instruction or enforcement, which means that human behaviour can be “nudged” in the direction that the service or product provider wants it to go.

“A ‘nudge’ is a small feature of the environment that attracts our attention and alters our behaviour. It turns out that if you give men a target, then they will aim,” Thaler says.

How to influence and persuade at work

Application in financial services

BI is “an inductive approach to policymaking that combines insights from psychology, cognitive science and social science with empirically tested results to discover how humans actually make choices”, according to the Organisation for Economic Co‑operation and Development (OECD).

The UK Behavioural Insights Team – also known as the “Nudge Unit” – has led much of the work in influencing public policy since it was established in 2010.

More than 200 BI initiatives are under way globally, including in the governments of the US, the UK, Canada, India and Australia, as well as various organisations globally, such as the World Bank, the United Nations and the OECD. Initiatives cover a range of policy areas such as healthcare, humanitarian aid, economic growth and consumer protection.

In Australia, the first BI unit was set up by the New South Wales Government in 2012. Victoria and Queensland now also have BI teams. At a federal level, the Behavioural Economics Team of the Australian Government launched in 2016.

BI is also increasingly used in financial services, both by businesses and regulators. In Australia, the Australia Securities and Investments Commission (ASIC) has a dedicated team that draws on BI to provide financial advice.

Sarah Edmondson, head of the Behavioural Unit at ASIC, says the team has used BI and behavioural science in the process of determining how to best protect consumers.

“ASIC has always had a strong focus on the evidence base about how consumers behave and interact with financial services and products. We have extensive experience in doing quantitative and qualitative consumer research to understand how real people behave and how that influences outcomes in the financial sector,” Edmondson says.

The biggest change to come from applying BI to the sector is the shift away from relying on disclosure as the key consumer protection offering.

This reflects direction from the 2019 Royal Commission into Misconduct in the Banking, Superannuation and Financial Services Industry for companies to treat consumers more fairly, says Edmondson.

“We set up the unit in 2014. At that time, there was a strong sense that the pre-existing focus on disclosure as a key regulatory tool was not delivering the outcomes that we really wanted to see. Relying on disclosure and information tools essentially means that much of the responsibility for avoiding harm is placed with consumers themselves in the first instance,” she says.

Instead, the team has focused on understanding the behavioural levers used by companies that offer financial products and services to determine if they contribute to consumer harm and poor outcomes.

“We use a behavioural approach to understand how the harms are manifesting for consumers. For example, with add‑on insurance in car yards, we went right through that customer journey to look at the various techniques that companies use to get people to purchase these products, which are often very low value.

“Until you understand what the problem is, and what is causing the poor outcomes, you can’t regulate effectively. Is it about changing the way the product is distributed? Is it a problem with product design?

Are incentives driving poor behaviour by firms? Will an information-based response help? Or is it about law reform – changing the way we regulate different products or services?” Edmondson says.

Behavioural economics at work

While BI broadly looks at how human behaviour is influenced, behavioural economics applies BI to a raft of different economic decisions, says Simon Russell, director of Behavioural Finance Australia.

“A good example is from the UK BI Team, which sent people a letter saying, ‘Did you know most people in your area have paid their taxes?’ instead of sending a letter demanding they pay their taxes. They measured it, and more people paid after receiving these letters.”

Communicating the message is a critical part of applying BI, says Russell.

“People are influenced by what other people do. If you want people to stop littering, do not put a sign up that says, ‘A lot of people litter here, please take your rubbish home’ because you are telling people that everybody litters here – so they will, too. The sign should say ‘Most people take their rubbish home. Please be like everybody else and take yours home, too’,” he says.

“The same can be applied in a commercial sense. Instead of saying ‘Not enough people have insurance’ or ‘Not enough people do estate planning’, we should be using positive social comparisons to encourage them to be like the people who are using insurance or estate planning.

“It comes down to the communications you send to clients that might make them more likely to engage with you.

How can you use insights about past behaviours to tailor what you provide to different client segments?” Russell says.

Applying BI

Showing people a different way to do things that is good for them is at the heart of BI, and this can be done at work, says Michelle Gibbings, workplace expert.

“Many of our decisions are instinctual – ‘this is how I respond in this situation’.

“BI is really understanding that we use these mental shortcuts, or heuristics, and we often make decisions that are not in our long-term best interest because we are unconsciously influenced by many factors that we’re not aware of,” Gibbings says.

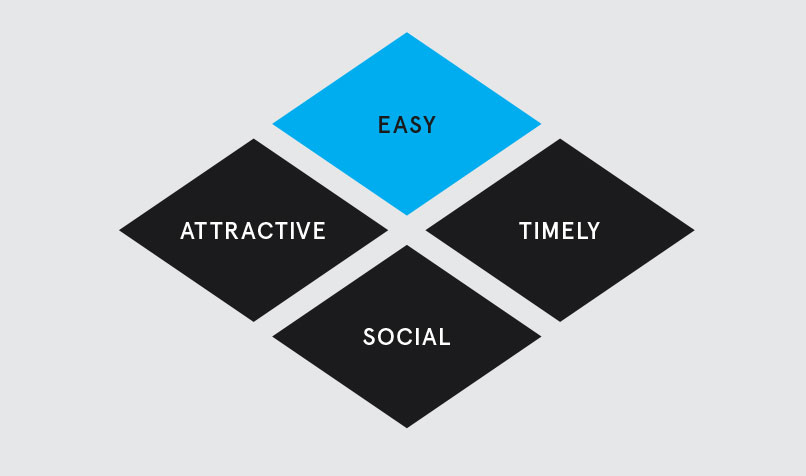

Gibbings points to the EAST framework, which was developed by the UK BI Team. The EAST framework is an accessible, simple way to apply BI in a workplace through periods of change – or when communicating workplace health and safety messages, for example.

“The EAST framework is ‘make it easy, make it attractive, make it social and make it timely’.

“Essentially, if you’re going to change a process, don’t make the process really complicated. Show how attractive it is and how it’s easy to do. Making it social, find ways to connect with people while you are doing it – and get the timing right with the training that’s needed when systems and processes are getting changed,” Gibbings says.

“There is plenty of research that shows we can be cognitively lazy. For example, we discount the future, meaning we will make a decision now to take a benefit, even if that results in us not getting a bigger benefit down the track.”

"BI is really understanding that we use these mental shortcuts, or heuristics, and we often make decisions that are not in our long-term best interest because we are unconsciously influenced by many factors that we’re not aware of."

Understanding the nature of our decision-making can help employers when communicating and trying to change behaviours at work, Gibbings adds.

“If you want to do things that are going to help people, then you need to make it easy for them. Think about how you can ‘nudge’ them in the direction that is going to benefit them.

“Google redesigned their lunch room to make the healthy food easy to get to and the unhealthy food harder to get to. What they found was that changing the layout meant people ate more of the healthy food simply because it was easier to get to. It’s simple, but very effective,” Gibbings says.

The power of persuasion

Examples of nudge theory from the UK Behavioural Insights Team

- When people in the UK were told in letters from the government that most people pay their tax on time, this increased payment rates significantly. The most successful message led to a 5 per cent increase in payments.

- Using personalised emails rather than generic messages significantly increased the proportion of people who gave a day of their salary to a good cause, as part of a trial with a major investment bank.

- Explaining that many people like to give money to charity in their wills increased donation rates from 9 per cent to 13 per cent.

- Sending people text message prompts to pay their court fines 10 days before bailiffs were due to arrive increased payment rates by two to three times.

- In New South Wales, a red “Pay Now” stamp was printed prominently on traffic infringement fine letters. This led to A$1.02 million in additional payments and 8800 fewer vehicle suspensions.