Loading component...

At a glance

- Consumer and generation categories are changing in nature due to increased migration and female presence in the workforce

- Demographic changes have also given rise to new groups of consumers.

- These changes are reshaping how goods and services are marketed.

By David Walker

“Demography is destiny.” The phrase has held the business mind since it was first spoken sometime in the late 19th century, and still does today. As a Deloitte consumer team wrote earlier this year: “A grasp of demographics is critical to understand what makes the world – and the consumer – tick. We are our demographics. Consumers’ behaviour, many business analysts believe, is shaped by demographic forces.”

Most business people know that consumers can be broken up into age demographics – baby boomers, generations X, Y and Z, and even generation alpha, the tag applied to today’s seven-year-olds and under.

Some of what you thought you knew about these different groups is no longer true. At the same time, the economy of the coming decades is being shaped by groups you may not have thought about much at all.

A fairer share

Data from the Workplace Gender Equality Agency (WGEA) shows that the highest-paid men in Australia are being paid at least A$162,000 more than the highest-paid women.

However, new research from Bankwest Curtin Economics Centre and WGEA finds women are progressing into full-time management roles at a faster rate than men (with the exception of CEO roles, which have seen very little change in gender diversity in the past five years).

Geoff Brailey of social research firm McCrindle notes that the past two decades have also seen a change in the attitude towards mothers in the workforce. In the 20 years to 2016, Brailey says, the proportion of Australian mothers in the workforce rose from 46 per cent to 53 per cent. A key reason for this is that women are now less likely to fall out of the workforce for long periods of time when they have children.

According to McCrindle’s figures, the proportion of mothers with post-school qualifications has more than doubled, from 23 per cent in 1996 to 51 per cent in 2016. That would be the most significant injection of skills and earnings potential into the Australian workforce over the past two decades.

Education is likely to keep that upsurge going. Women now make up the majority of university students – 58 per cent in Australia, which reflects the global pattern. It’s also evident in East Asian markets, from China and Hong Kong to Malaysia and Vietnam (although not in Japan, where female undergraduates remain a minority).

The rise in women’s roles extends to board level. Women account for 30 per cent of board members in ASX200 companies. In 2018, 45 per cent of all appointments to these company boards were women. Many of the iconic symbols of wealth – sports cars, prestige watches and yachts – are overwhelmingly marketed to men, and marketers will need to adapt.

The cohort of women that entered the workforce in the past 10 years, and the group that will enter in the next 10, are more highly skilled than ever before. Within two decades, according to a recent WGEA report, Australian women could account for half of the country’s manager positions.

All this adds up to a world in which women can be expected to work more and earn much more. These increasingly wealthy women will continue to remake the consumer landscape, demographer Simon Kuestenmacher explains. “This is not the majority of women, but it is a very fast-growing sector of women, highly educated women,” he says.

Kuestenmacher believes this group is happy to be marketed to.

One industry that is rapidly becoming aware of the need to recalibrate for a female client base is wealth management. US firm Ellevest’s pitch to clients is that 86 per cent of investment advisers are men over 50 – and that women have different investment needs to men.

Differences in female consumer behaviour are not new. Women have been major household decision-makers for much of the past century. What is different now is the resources they are able to command, both in families and on their own, particularly in the years after child-rearing.

Many of the iconic symbols of wealth – sports cars, prestige watches and yachts – are overwhelmingly marketed to men, and marketers will need to adapt.

The boomers' inheritors

Earning is only one way in which women are set to grow their wealth. The demographic bulge of the 20th century is not yet done exerting its influence, and even in their passing, the baby boomers will remake the world once more.

It’s been dubbed the “great wealth transfer” – baby boomers, the wealthiest generation in global history, will begin to die of old age over the next decade. Their trillions of dollars in wealth will go to their boomer spouses and then to their children in generations X and Y.

In the first instance, many of those recipients will be women, simply because women, on average, outlive their husbands. Compared to previous eras, inheritances are now more likely to find their way to daughters as well as sons.

“Women are going to inherit from their parents and their husbands and be stewards of immense amounts of capital,” says Clare Payne, an ethics and trust strategist at EY.

City centre residents

For decades after World War II, the citizens of developed nations headed for suburbia, from London to Perth to Auckland. Inner cities were hollowed out and demographers talked of “donut cities”.

However, changing attitudes, government incentives and the increase in high-income city jobs have drawn people back to inner cities over the past two decades. For instance, figures show that densities in Melbourne, the epitome of this trend, rose from 2263 inner-city residents per square kilometre in 1991 to 3944 residents two decades later. At the same time, incomes for these residents have soared.

All over the world, the inner city has moved from decline to densification, from grungy to grand, and the trend shows no sign of reversing. Inner cities are now prime territory for marketers looking to sell to an upscale demographic.

Recent migrant groups

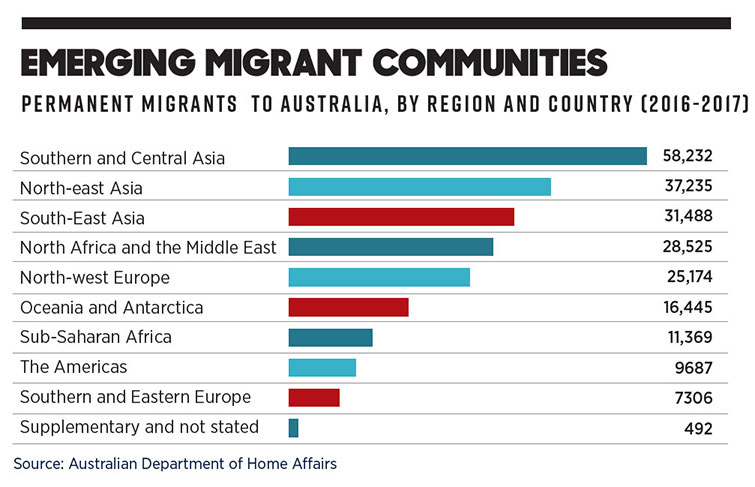

Australia’s immigration numbers are near 50-year highs as a proportion of total population growth. Migration rose throughout the late 1990s and 2000s under governments of both political persuasions, and while numbers peaked in 2010, they have fallen only a little since then. New Zealand’s net migration intake jumped after 2012 and remains high.

Singapore has a higher rate of net migration still – in 2017, it had the highest of any Central or East Asian nation, a result of its government’s battle against a low fertility rate.

The result is a rapid change in the shape of Singapore’s population, with new immigrants ranging from Asian and Western professionals to lower-skilled immigrants, all seeking a future in one of the region’s most dynamic yet stable economies.

The squeezed

A group that might seem unpromising in terms of consumerism is the one that might be dubbed “the squeezed”: lower and middle-income earners whose weekly commitments leave them little room for discretionary spending.

“In many OECD countries, middle incomes have grown less than the average and in some they have not grown at all,” the OECD (Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development) said in a report this year. In general, middle-income households’ spending increased faster than their incomes before the global financial crisis, fell between 2007 and 2010, and has remained stagnant since. More than half of middle income households’ budgets are devoted to core items such as housing, food, clothing, health and education.

Yet even here, Brailey notes, companies are finding ways to sell new services and products. A recent winner has been subscription internet entertainment, where brands such as Netflix and Foxtel offer subscriptions for as little as $10 a month. Brailey describes this as “a way to market high-value products at low entry points”, noting these subscriptions have been structured to avoid what he sees as a “contract avoidance” culture. On a different scale, Kuestenmacher believes the income squeeze will drive increased demand for affordable rental housing.

CPA Library Resource:

Generation Z joins the market

In 2017, the first members of Generation Z turned 21; by 2025, McCrindle has calculated, they will make up 27 per cent of the workforce. Globally, says McCrindle, they are the largest generation ever.

In wealthy nations, this group is connected through digital devices and engaged through social media. “TV” is more likely to mean Netflix than free-to-air, and “media” frequently means material that they create and send to other people rather than something created by a corporation. Compared to older generations, they’re far more likely to want not to be marketed to. It’s hard to win their total attention, especially with a message that smacks of conventional media communication.

You should make sure your service or product warrants their notice, and tell them a story about it that will capture their attention. Even then, be prepared to hear negatives as well as positives.

From alpha women to generation Z, changing demographics present new challenges and opportunities. It’s up to businesses to research and find ways to reach the new consumers.

Additional research by Jason Murphy.

Traditional generations

Post-war cohort

Born: 1928-1945

Age in 2020: 74 to 92*

Grew up in a Cold War environment and tend to value security and the familiar.

Baby Boomers

Born: 1946-1964

Age in 2020: 55 to 73

Grew up in post-war prosperity. Early boomers experienced the Kennedy assassination and Vietnam; later boomers came of age in the post-oil shock, post-Whitlam government era.

Generation X

Born: 1965-1980

Age in 2020: 39 to 54

This generation was exposed to more childcare, divorce and economic upheaval than its predecessors.

Generation Y or Millennials

Born: 1981-1996

Age in 2020: 24 to 38

They are on average more sophisticated, more technology-wise and more ethnically diverse than their mostly baby boomer parents – and more resistant to marketing pitches.

Generation Z

Born: 1997-2012

Age in 2020: 8 to 23

This group grew up with the internet, technology, smartphones and worldwide social media.

* Age groups are approximate and reflect marketing usage.