Loading component...

At a glance

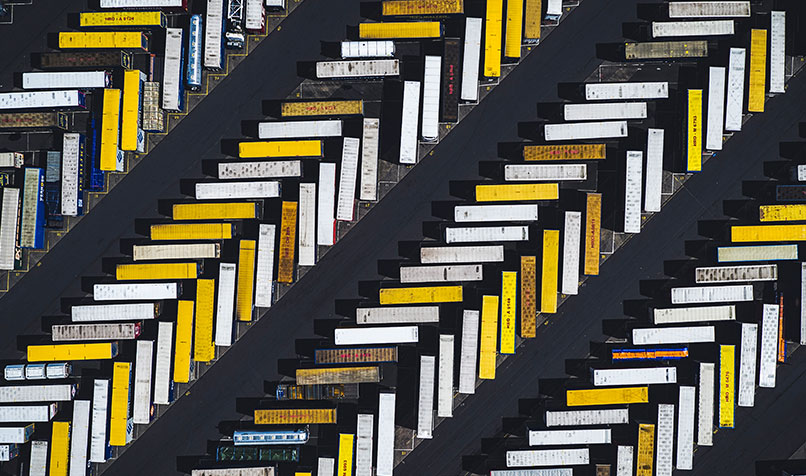

- The massive disruption in global supply chains has demonstrated the risks of being over-reliant on a few overseas suppliers.

- The challenges have prompted calls for a retreat from globalisation in order to become more self-sufficient and move away from just-in-time manufacturing.

- However, experts explain that dismantling trade partnerships is neither practical nor sustainable, and that the more sensible way forward is to diversify sources of supply.

The business risk that is our current reality – the disruption of global supply chains – is nothing new. Granted, we have never previously witnessed the risks on such a large scale, but the risk itself has long existed.

Take, for example, Australia’s fuel security. Despite the International Energy Agency requiring member nations to stockpile the equivalent of 90 days of annual net imports, in mid-2019, Australia held stocks of petrol, diesel and jet fuel sufficient to last only 18 days, 22 days and 23 days, respectively. In the event of a supply chain disruption, the entire nation would grind to a halt after just a few weeks at normal usage.

Following the decision made by a number of refineries in Australia – including ExxonMobil, BP, Caltex and Viva Energy – to close polluting refineries and to rely instead on sourcing refined fuel from Singapore, which itself sources its crude oil from the Middle East and South-East Asia, Australia no longer enjoys liquid fuel security.

The public discourse in Australia has focused on the dangers of heavy reliance on limited numbers of suppliers for any important product. It centres on the problems of long and therefore easily disrupted international supply chains in an increasingly fragile geopolitical environment. In some quarters, that conversation has turned to the idea of decoupling from major trading partners.

Are we seeing the emergence of a new type of nationalism, a return to a perceived security of production? Some aspects of a return to a semblance of security are sensible and achievable, and some are downright impossible. What is clear is that no part of this return will be straightforward.

Dismantling partnership is not the answer

The confidence that has built around the highly globalised system has encouraged the idea of ever-increasing efficiency and performance, says Dr Paul Barnes, head of the Risk and Resilience Program at the Australian Strategic Policy Institute.

This confidence has led to a drive for cost reductions, has spawned well-established expressions of manufacturing and retail, such as just-in-time production and just-in-time delivery, and has created the environment in which our fuel security issue could become a reality.

“We’ve had this notion of supply chain continuity as a given. But unfortunately, security issues and biosecurity issues have proven quite shockingly that the world isn’t as simple as certain models or assumptions would suggest,” Barnes says.

To those who suggest decoupling from major trading partners, Barnes’s blunt answer is that it’s a silly idea.

“Globalisation is a phenomenon that has evolved over many years,” Barnes says. “In fact, ever since humans have shared, traded and bartered, we have been in a process of globalisation. It’s not something you can just switch off. Diversifying sources of supply is important, though.”

Dr Pichamon Yeophantong, international relations and China foreign policy specialist and senior lecturer at University of New South Wales, Canberra, agrees.

“The path towards decoupling isn’t as straightforward as some politicians or commentators would like to make it appear,” Yeophantong says.

“Ultimately, it means having to rejig national economic strategies and recalibrate Australia’s industry focus. There would obviously be serious implications for trade, investment and employment, specifically in the resource, agricultural and manufacturing sectors. This change is not something that can be easily achieved, if at all. Australia needs to become more resilient, but not fixated on costly protectionism.”

Rather than decoupling from major partners, Yeophantong says, using a “plus-one” approach is more viable. This is an approach that Japanese manufacturers have taken when it comes to securing vital resources, not just internationally, but on the national basis as well.

For example, if a Japanese car maker requires particular widgets that it sources from a factory in one part of Japan, it will often source the same widgets from another factory in a different Japanese region to mitigate supply chain risk caused by natural disasters.

Supply chain problems brought on by COVID-19, Yeophantong says, have heightened sensitivity around dependency on a single partner or source of imports. Plus-one is a sensible risk reduction strategy.

The one to watch

Vietnam, many argue, will be the growth story of the next few decades.

As organisations increasingly search for their plus-ones, they will find them in Vietnam, experts say.

A country of 97 million people, Vietnam has none of the ageing population issues shared by many of its neighbours, including Australia. Two-thirds of its working-age population is under the age of 35. Before the pandemic, GDP was growing at about 7 per cent annually, and foreign direct investment was plentiful.

Vietnam shares an over 1400-kilometre terrestrial border with China, and enjoys the benefits that come with a coastline stretching over 3000 kilometres, including several high-quality, deep-water ports. It has high levels of smartphone penetration, fast-increasing internet access and a labour force with wages about a third of those in China.

Dr Can Van Luc FCPA is chief economist at the Bank of Investment and Development of Vietnam (BIDV), the country’s largest commercial bank. In his position – geographically and professionally – he is at the epicentre of a potential economic and societal revolution.

Luc says there are several main drivers of Vietnam becoming central to the future of the global economy.

"Ever since humans have shared, traded and bartered, we have been in a process of globalisation. It's not something you can just switch off. Diversifying sources of supply is important, though."

The first is the fact that the nation has been very successful in controlling the spread of COVID-19. The official reopening of the Vietnamese economy occurred on 23 April, a time when many others were only at the beginning of their shutdowns.

“Even with everything that has happened this year, we still forecast our economy to grow at 4 per cent to 5 per cent in 2020, and it will bounce back strongly to grow at about 7 per cent in 2021,” Luc says.

“The next driver is investment, both foreign and domestic. For foreign direct investment, we have seen investment relocation from Mainland China and Hong Kong to ASEAN, India and Vietnam. Vietnam has been considered one of the very top priorities.

“Domestic private investment has been growing at more than 10 per cent per annum during the past five years, because the government has worked hard to create good conditions for the private sector to develop.”

One of the problem areas in Vietnam has been its interior infrastructure, with troubled areas including airports, railways and motorways. The government has recognised this and has boosted infrastructure development, with a focus on these weak areas.

Another driver is private consumption, which is equal to about 70 per cent of GDP and has also been growing fast, at about 10 per cent per annum over the past three years. It has contracted by 3.9 per cent in the first five months of 2020, but the May figure was 28 per cent higher than that in April 2020, and the government has used various measures to continue to boost domestic demand.

“The final driver is the digital economy,” Luc says. “We have a young population, and they are very keen on technology. Vietnam is where the manufacturing of Samsung smartphones happens now, so they are affordable, and about 60 per cent of people who are telephone subscribers now use smartphones.”

Risks around growth, Luc says, include the ongoing issue of the pandemic, the China-US trade war and tensions in the South China Sea. Domestically, there are also concerns about climate change and air pollution.

Manufacturing in Australia

It is excellent news for Vietnam – and for all nations that serve to benefit from it – that the country’s economy is set to continue growing. However, what about the argument that more manufacturing should be brought back inside national borders?

Simon Ringer, professor of materials science and engineering, and academic director of core research facilities at the University of Sydney, says we need to ensure the discussion doesn’t become nationalistic and jingoistic.

“It is a sound idea, but we will have to pick very carefully the capacities that we invigorate,” Ringer says. “We will have to start from our niche capacities and work out from there.

“‘Sovereignty’ is a word that’s being thrown around a lot. It’s an important word, and it absolutely has its place, but let’s remember, there’s no such thing as scientific sovereignty.

“We must act local, but think global. We need our great young engineers, scientists, designers, economists, accountants and business people to continue to have opportunities to work in overseas companies and jurisdictions.

“More than ever, we want local talent with global experience and networks. We want that talent contributing back in to our capability, raising our capacity in manufacturing and other sectors.”

Interestingly, Ringer says, in an era of COVID-19, this kind of career arc might all happen with the individual not changing their postcode. Many companies are operating global operations via secure intranet.

“The idea that we somehow close the shutters and do everything in Australia has no business case,” he says. “Advanced manufacturing is a big opportunity for Australia. Let’s be proactive about that, but let’s not get into nationalistic conversations about decoupling, because it simply can’t work.”

CPA Library resource:

Regional value chains

Regional economic integration back in focus

Dr Pichamon Yeophantong says Australia needs to prepare for greater regionalisation that puts it in its geographical place – as an important part of Asia.

“The question of whether we’re moving away from globalisation is interesting. Especially given the domestic unrest within the US right now, many argue that COVID-19 is sounding the death knell not just for globalisation, but also for US hegemony and the liberal international order. As a result, what I think we’ll see is accelerated regionalisation.

“That’s where existing arrangements like the ASEAN Free Trade Area become even more prominent,” Yeophantong says. “We’ll see a shift in focus to strengthening regional value chains as well as deepening regional economic integration.”