Loading component...

At a glance

- At the start of the pandemic, some industry insiders predicted a 30 per cent decline in house prices in Australia over a 12-month period.

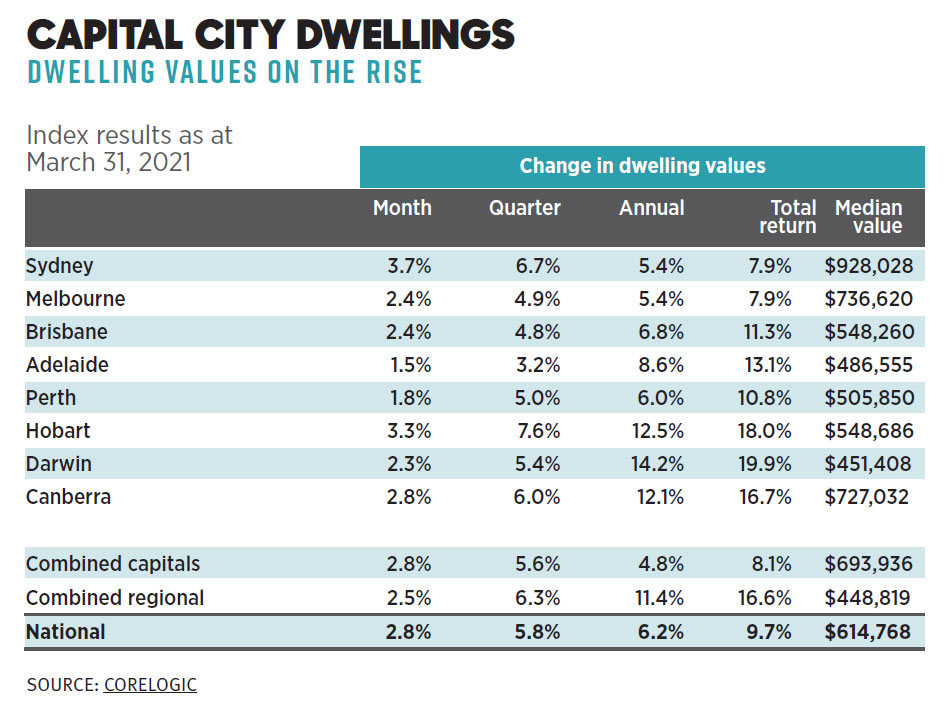

- Instead, house prices have been increasing at the fastest rate in 32 years, rising by 2.8 per cent in March 2021 alone.

- The resilience of the property market is caused by a number of factors including stimulus measures, constrained consumption and investment choices, and low interest rates.

By Johanna Leggatt

For almost two decades, the unstoppable march of the residential market has been one of the dominant narratives of the Australian property sector. It is an enduring story of smashed sales records, desperate first home buyers and packed crowds at auctions, fearful of missing the boat.

Then the pandemic hit, and it seemed that the run was over. Last year, many property analysts warned of doom and gloom, with some industry insiders predicting a worst-case scenario of a 30 per cent decline in house prices over a 12-month period.

However, Dr Cameron Murray, an independent economist and post-doctoral fellow at the University of Sydney’s Henry Halloran Trust, saw the situation differently.

In May last year, Murray argued the case for a bull property market, and said the housing market was far more likely to boom than crash in the aftermath of lockdowns.

When he posted a link to his argument on Twitter, the backlash was severe.

“People thought I was insane,” Murray says. “I have since reminded people quite a few times to check out the response to this tweet a year ago.”

Nowadays, Murray feels vindicated. According to property data analyst CoreLogic, Australian housing prices have been increasing at the fastest pace in 32 years, rising by 2.8 per cent in March 2021 alone. Between January and April 2021, Sydney’s median house price rose by A$100,000.

The perfect storm

Why is the Australian property market showing such remarkable resilience?

Murray says we need to cast our minds back to three years prior to the pandemic, when the Australian property market experienced a large price adjustment.

“You don’t usually get crashes after three years of nothing. You get crashes after three years of unbelievable price growth,” he notes.

It also helps to think of the Australian housing sector as part of a broader global market that has also seen price rises in the past year.

Murray points out that, in the US state of Arizona, prices rose by 30 per cent over the course of this year, while Auckland has seen a more than 20 per cent rise in housing prices. There have been steady rises in Europe as well, particularly in Germany and Denmark.

"Australia does not have a coherent national housing policy, and this is unlike many countries that see it as a very important duty to house people."

“It’s important to remember that it is very hard for [Australia] to just crash all on our own,” Murray says.

Another contributing factor in Australia has been historically low interest rates, which makes money cheap to borrow.

Consumers’ spending options have also been limited by restricted choices – no international holidays, no music concerts or theatre performances, no going out to bars and restaurants. At the same time, individuals also increased their savings due to concerns around their job safety and businesses.

“I think we also forget that Australia had an outsized stimulus last year,” Murray says. “I calculated it was five times bigger than the post-GFC stimulus in terms of cash payments to households.

“Now everybody is a bit cashed up. We can see more people competing at those higher prices for property because they can borrow at low interest rates.”

Do prices need to drop?

Many experts argue that something needs to be done to make property more affordable and accessible for lower and middle-income households.

Dr Andrea Sharam, senior lecturer with the School of Property, Construction and Project Management at RMIT University, highlights the inherent conflict in housing being both an essential need and a highly lucrative investment.

“Australia does not have a coherent national housing policy, and this is unlike many countries that see it as a very important duty to house people,” Sharam says.

“In terms of policy, we have one foot on the accelerator and one on the brake.”

In particular, she points to the capital gains tax (CGT) concession, which offers a 50 per cent CGT discount on capital gains generated for investment properties.

The discount applies to capital gains generated on all asset classes held for 12 months or more.

“This capital gains tax concession is one of the key drivers of unaffordability, and since it was introduced in the Howard era, house prices have just gone up and up,” she says.

In addition to reforming CGT, Sharam believes Australia needs more housing that is not entirely within the “speculative sector”.

"We need to expand social housing, because we have lots of low-income people in Australia who cannot afford private rental, let alone purchase housing,” she says.

“The private rental sector has also grown hugely in the last 30 years, and we don’t have that culture they have in Northern Europe with regards to tenant protection.”

Sharam would also like to see institutional build-to-rent developments encouraged through tax incentives.

Build-to-rent developments are typically owned by institutional investors, such as superannuation funds, for the long term and offer tenants more secure, long-term leases.

“Let’s fix up the tax regime, so that the build-to-rent proponents have advantages, because these are long-term investors who are not ‘flipping’ properties – they are in there for the rental yield, so they will make really good landlords, and they will build quality housing,” she says.

Sharam is also keen to see a scrapping of the state-based stamp duty tax paid by the house purchaser in favour of an annual land levy: a proposal, incidentally, that has been floated by the New South Wales Government.

“Paying this huge lump sum [to the government] when you purchase a property makes life difficult,” she says.

When governments intervene

Do prices need to drop?

Over the past decade, the Australian Government’s solution to housing affordability has taken the form of grants for first home buyers, building schemes and incentives to encourage people to save for a deposit for their first home.

Far from making home ownership more accessible, these schemes “add fuel to the fire”, says Sharam.

Murray agrees and says these are the sorts of policies governments announce when they “don’t want to do anything serious about the housing market”.

However, Murray is not a fan of manipulating the asset price through tax settings, and sees this as a political “hot potato” that no government would touch.

The housing market is already worth A$8 trillion, he says. “If you try to intervene in that market to halve the cost of housing, there’s A$4 trillion disappeared off the balance sheets of the wealthiest 60 per cent of home owners, concentrated in the wealthiest 18 per cent who are landlords, and it’s a political impossibility.

“There’s never been a wealth redistribution in history that large without a war or a revolution.”

Instead, Murray floats the possibility of a “parallel system” in which the property buying and investor classes are untouched, but the federal government opens “a secret door” to the market at cost price.

“For example, a national housing developer could build 50,000 dwellings a year [on the condition] that they can only sell to people who don’t already own housing, at construction cost price with a discount line,” he says. “Then, you flood the market with supply.”

This kind of approach is not without precedent. Government intervention in Singapore has allowed residents to access secure housing in an affordable fashion, Murray says, through its Housing and Development Board (HDB).

The HDB offers flats for sale for a subsidised price, and there are tight regulations around selling and renting out your HDB home.

"A lot can change in 20 years, but... I expect population growth to return and the sector to thrive, if not boom."

Murray points out that, in Singapore, about 80 per cent of people live in government-built housing. “Essentially, they have created what we have in our public health system, but for housing,” he says.

In Mainland China, Shanghai residents wishing to buy a house need to go through a newly announced lottery system that scores them according to their need for housing.

Under the rules, announced earlier this year, preference will be given to families without existing housing. A five-year ban on the resale of new houses has also been announced to cool the market in Shanghai.

New Zealand has recently introduced strong measures to rein in its runaway housing market, with an extension to the investor holding time to receive tax offsets – known as the bright-line test – from five to 10 years to curtail investor flipping.

While acknowledging the New Zealand market was overheating, Elinor Kasapidis, CPA Australia’s senior manager tax policy, is not convinced the proposed tax changes are appropriate or “will be effective to cool it down”.

“The supply and demand of residential property is a complex issue and warrants a considered response,” she says. Property investors who don’t need to borrow to fund their purchases will be unaffected by the loss of deductions, Kasapidis maintains.

“It’s hard-working New Zealanders trying to get ahead by purchasing an investment property who bear the brunt of this change,” she says.

“The extension of the bright-line test... is not unreasonable, but may suppress turnover in much the same way the imposition of stamp duty does in Australia.”

Downside to government intervention

Do prices need to drop?

Pete Wargent, international property buyer, finance and real estate expert and co-founder of property buying company AllenWargent, does not endorse government intervention as a tool for taking the heat out of the market and making housing more affordable.

In particular, he is opposed to the Reserve Bank of Australia using policy levers, such as instituting limits on the percentage of high loan-to-value loans and enacting greater scrutiny over borrowers’ income and expenditure.

“Overzealous macroprudential measures choke off the credit supply to the economy, as small business owners also use equity from housing,” he says.

Instead, more affordable housing should be built to address the issue of younger people being priced out of the market.

“Realistically, sizeable blocks of vacant land will be hard to come by in the capital cities in established suburbs, so planning should allow for unit developments on brownfield sites and above train stations,” he says.

Social housing is important, too, Wargent argues, but notes there doesn’t seem to be much political will in this direction, “even at a time when we’re running a massive budget deficit”.

“I wouldn’t hold out much hope when the talk returns to balancing the books,” he says.

As far as the next two decades are concerned, Wargent does not foresee a property crash on the horizon. In fact, he intuits the opposite.

“Real estate tends to be cyclical, so the cycles will likely continue,” he says. “A lot can change in 20 years, but Australia is a clean, safe and desirable country, with an open economy, a free-floating currency and control of its own monetary policy, so I expect population growth to return and the sector to thrive, if not boom.”

Are we in a property bubble? “Not at the moment,” he says.

“There may be some nascent risks just beginning to emerge in some regional markets, if there is a population shift back towards the capital cities in the coming years, but it’s hard to say we’re in a bubble with [mortgage] serviceability at the easiest levels in decades.