Loading component...

At a glance

By Jason Murphy

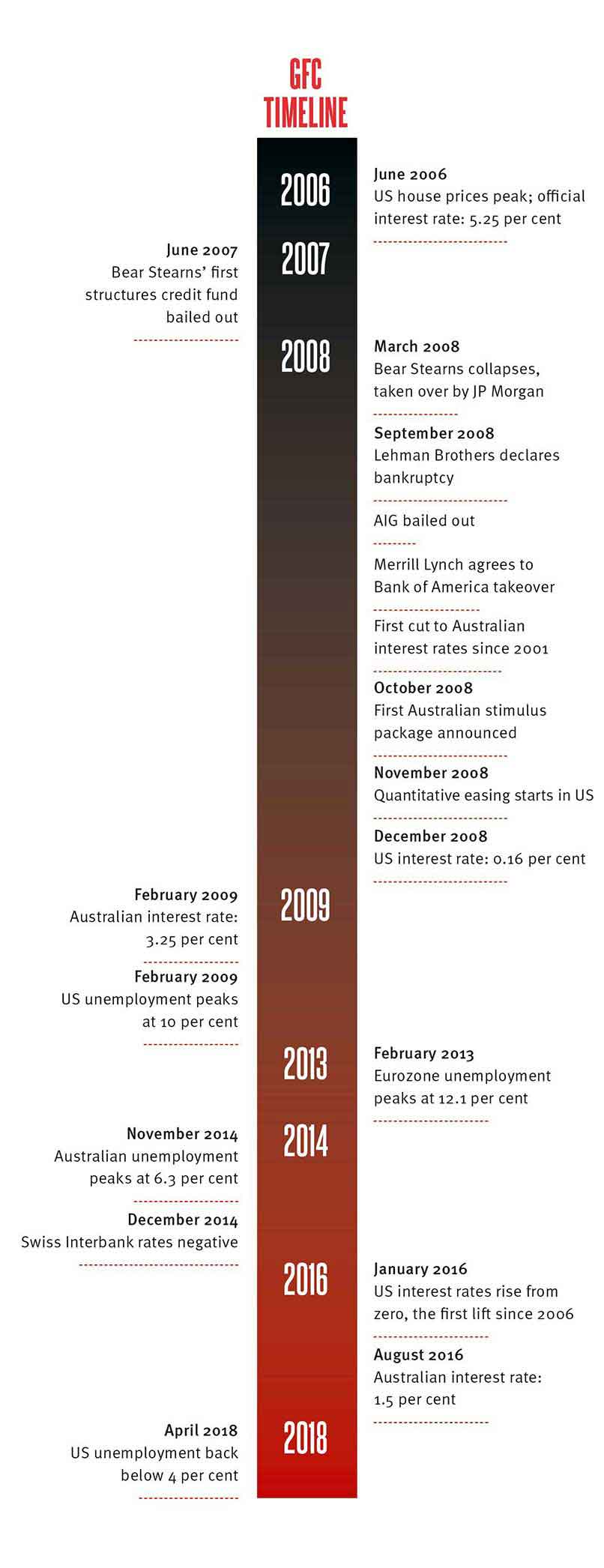

The lead-up to the global financial crisis (GFC) was a different world.

Kevin Rudd was the fresh-faced prime minister of Australia. George W. Bush was US president. Taylor Swift was still writing country songs, and the Western world was far more worried about Al Qaeda than mortgage derivatives.

When then Reserve Bank of Australia governor Glenn Stevens spoke at a business forum on 14 June 2007, he noted how strong growth and borrowing was.

“There is, at the moment, moreover, a high degree of confidence about the future,” Stevens observed.

By early 2008, the official tone would change. Mild concern crept in, as investment bank Bear Stearns required a sudden bailout. By late 2008, panic had begun.

“When Lehman Brothers fell over, the whole world exploded and the global economy fell off a cliff,” says Wayne Swan, treasurer of Australia at the time.

“We were into crisis management for about 12 months.”

Elizabeth Moran was working on the trading desk at bonds trader FIIG Securities when Lehman collapsed.

“The whole market was just dumbfounded really. Couldn’t believe it,” Moran recalls.

“There was chaos because people realised that the government could let other big institutions go – Fannie Mae, Freddie Mac, Citigroup, AIG, the big insurer – there were a number of really big global companies, they were massive, how on earth were they going to look after all of them?”

Fear showed in plunging stock markets. The S&P 500 Index finished 2008 down nearly 40 per cent, its largest yearly fall in history.

“A lot of it was a blur,” says St George Banking Group chief economist Besa Deda.

“Every day you came in and there were more falls across share markets and financial institutions in difficulty.”

Amid the whirlwind, as the world grappled with the completely unforeseen disaster, Deda’s role changed.

“At the height of it as economists we weren’t asked any more to forecast when it [would] go away, but asked more to explain what was happening,” she says.

At the root of it all was a long period of self-serving behaviour.

Below prime

The fundamental ingredient of the global financial crisis was bad lending. Sub-prime loans were even available to people with no income, no jobs and no assets – so-called NINJA loans.

Many of the loans were “non-recourse”, which permit a borrower to return the asset if they cannot repay. That structure, common in the US but not the rest of the world, made bad loans the bank’s problem.

“I can remember having to ask somebody what a non-recourse mortgage was,” says Saul Eslake, who at the time was chief economist at ANZ Bank. “It had never occurred to me that banks would lend housing finance on a non-recourse basis.”

When borrowers owed more than the asset was worth, they took full advantage of the non-recourse feature and handed the keys to their home back to the bank. The term “jingle mail” was coined to describe envelopes full of house keys arriving at lenders. Banks took the losses.

"It never occurred to me that banks would lend housing finance on a non-recourse basis."

The mess might have been contained had investment banks not been so vigorous in dicing up these rotten pieces of financial meat into complex financial assets and spreading them throughout the financial system.

Securitised mortgages and their derivatives were spread far and wide, but nobody could say where exactly. It was the uncertainty that caused the financial system to halt. Nobody would lend to another party that might be insolvent. Weakness soon spread from the financial sector to the real economy, and that is where it bit hardest.

A financial crash and subsequent recession are not just lines on a graph. Nor are they simply a puzzle for academic economists to unpick. They cause stress, family breakdowns, poverty, suicide and ill health. They leave human potential untapped. Their legacy is intense and highly personal.

The global policy response

The GFC was an enormous shock. The response was possibly even more so. Around the world, policy was pushed to the very edge.

By the start of 2009, the US Federal Reserve had already turned on the taps with an experimental policy it called quantitative easing (QE). Liquidity was injected into the financial system in an attempt to loosen financial conditions and to keep credit flowing. QE would soon thereafter be adopted in Europe and Japan.

Interest rates fell to zero in much of the world. Then, in some places, they broke through that barrier. The hitherto hypothetical concept of the “zero lower bound” for interest rates was tested. The world found it was not such a boundary at all. Interbank rates fell as low as -0.85 per cent in Switzerland and -0.3 per cent in Denmark.

"The experience is that the build-up of financial risks like those seen in China is almost always followed by a marked slowdown in GDP growth or a financial crisis."

China, meanwhile, unleashed a spending program worth US$600 billion, pump-priming on a scale the world had never before seen from a comparably sized economy.

Each of these extraordinary policy responses – whether fiscal or monetary – may have helped avert a worse crisis. Nevertheless, their full cost is hard to judge. Government budgets are still recovering from the GFC a decade later, but the consequences of keeping global interest rates extraordinarily low for such a long time may yet be the greatest legacy of the crisis. Bank of England records suggest current interest rates are the lowest in recorded history – and that record goes back hundreds of years.

Risk is building, says Deloitte Access Economics economist Chris Richardson. “Those low interest rates have led to a build-up in debt and debt is ultimately a degree of vulnerability,” he says, suggesting many asset markets around the world look inflated.

The GFC in Australia

Australia’s GFC was famously mild by comparison to the rest of the world. In no two consecutive quarters did the country experience negative GDP growth, meaning Australia never entered recession. Unemployment rose, but only to 5.8 per cent, far below the 10 per cent rate in the US.

In Australia, interest rates were slashed during 2008, but the major line of defence was spending. Treasury chief Ken Henry coined the phrase: “Go hard. Go early. Go households.” The government mailed A$900 cheques to millions of Australians at a cost of billions. Spending went beyond households as well, to build school facilities and subsidise home insulation.

The legacy of Australian spending is hotly debated. Was the spending too much? Did it add too much to debt? Was there a way to back out? Eslake argues it was better to plan to spend too much than too little, but that the opportunity to trim back should have been grabbed as soon as the Reserve Bank began to raise rates in 2010.

“My criticism of the fiscal policy response of Australia is not that we did too much – even though we did – it is that once it was clear we had done too much, we didn’t wind it back,” Eslake says. He rues the higher than necessary debt levels that resulted.

Swan, the man who helped open the purse strings as federal treasurer at the time, sees the resulting uptick in debt as more benign.

“I have never had a fetish about debt,” he says. “Debt is an important part of the fiscal armoury that you use to support your economy.”

Asked about the legacy of the GFC, Swan says, “It told us that Keynesian economic policy is as important as ever and reminded us of the importance of fiscal policy as a structural tool.”

Big spending in the early days of the GFC indeed helped avert a greater disaster, but some of the most relevant spending came from China. The yuan avalanche released by Beijing contributed to Australia’s plain sailing, and the effect of continued Chinese growth on commodity prices did the rest.

By 2011, three years after the financial crisis was most acute, American unemployment was still 9 per cent and Europe was in the thick of a major debt crisis. Australia was in decent shape. Terms of trade were at a record high and the unemployment rate was just fractions of a per cent above 2007 levels.

The GFC may not have ravaged the economy, but it depleted Australia’s buffers. The budget is in worse shape than it was prior to the GFC, and official interest rates are far lower, Richardson explains.

“Whether or not it is another GFC-like event, the ability to fight off the next recession in Australia is perhaps not as good as people think,” he says. “Your two obvious sources of firepower are what the Reserve Bank can do and what the federal budget can do. The fire hose is attached to a smaller engine than it was in 2008-2009.”

That means that the next crisis will be harder to manage.

Ben Bernanke and quantitative easing

“The Lord works in mysterious ways,” Eslake says.

“If you want evidence for that in this context, it would be that the person who was in charge of the Federal Reserve at the time was the one guy who knew more than anybody else on the planet about the mistakes that had been made in similar circumstances in the early 1930s.”

US Federal Reserve chairman Ben Bernanke was indeed well qualified for a crisis. Much of his academic career had been spent researching the Great Depression, which the US central bank arguably exacerbated by reducing monetary supply. It is fitting Bernanke’s signature decision was to engage in quantitative easing.

Pumping liquidity into the financial markets was designed to keep monetary conditions loose without having to reduce nominal interest rates to negative territory. If you look at the US unemployment rate, it is hard to conclude quantitative easing was anything but brilliant.

Unemployment fell steadily and strongly from 2009 to 2018.

Bernanke himself writes that there exists “a broad consensus that QE has proven a useful tool, with demonstrable effects on financial conditions”.

Quantitative easing was primarily a way of stimulating the domestic economy, but it had a side effect in foreign exchange markets. The US dollar was depressed on global markets. In 2012 and 2013, as Europe and Japan also adopted QE in earnest, headlines spoke of “currency wars”.

If such wars were being fought, Australia was caught in the crossfire. The Australian dollar – which had plunged in the depths of the crisis in 2008 – rose as high as US$1.10 in 2011. US exports were at a sale price.

Bernanke retired in 2014, and his career must be judged a success, but the final chapter is not yet written. Quantitative easing involved taking assets onto the US Federal Reserve balance sheet for the liquidity that was released. The value of those assets topped US$4 trillion.

As 2018 goes on, that accumulation is finally being reversed – gently – in a manoeuvre some are calling quantitative tightening.

Will this tightening of policy cause a reverse situation that strengthens the US dollar? What will the effects be? Bernanke’s legacy cannot be judged until we know.

Big bad banks

The global financial crisis changed the landscape for financial entities. Not only are there new regulatory and capital requirements, but banks face a far less sympathetic public. Suspicion of the financial sector is now a global phenomenon.

The consequences are rife, and recently manifested in Australia’s 2018 Royal Commission into Misconduct in the Banking, Superannuation and Financial Services Industry.

That is resulting in policy changes that are costing the financial sector, says CPA Australia’s late head of policy Paul Drum FCPA, citing recent changes to superannuation fees and add-on products announced in Australia’s federal budget.

“Here’s a government response already, to say these things are wrong and they’ve been eroding your investment,” Drum says. In thinking about a backlash to mainstream finance, he also points to cryptocurrencies such as bitcoin.

“A lot of the crypto arguably came out of the GFC,” Drum says. “People looked for alternatives because they didn’t trust mainstream finance houses.”

Bubbling below the surface

Are we in a bubble? This question is being asked in real estate markets from Stockholm to Sydney, not to mention the Nasdaq index and bond markets. Great herds of unicorns (private tech firms valued at over US$1 billion) roam Silicon Valley, dazzling the eye without delivering much in the way of profit.

The pattern of asset price inflation around the world is dappled. Not all markets have risen amazingly, as Australian stock investors can attest. But when economists and analysts see so many outbreaks of dramatic upward revaluation coinciding, they get to wondering whether the low interest rate environment isn’t perhaps exerting an effect.

“It is not a coincidence that the countries that have had the highest inflation of their property values in particular have been the advanced economies that did not have a financial crisis,” Eslake says.

He maintains that banks in places such as Sweden, Canada and Australia were willing to lend during the period of ultra-easy monetary policy, and met an eager group of borrowers.

“People in those countries were willing to respond by borrowing, whereas in America and Britain and many other continental European countries households and banks were too scarred by the experience.”

Cheap money is supposed to drive the real economy. This is the guiding principle of monetary policy: cutting interest rates will spark consumption and investment in productive assets.

Rising prices of houses or financial assets are just a side effect, but the experience of Australia and many other parts of the world since the GFC is more complex.

Rising asset prices seem like a primary effect of easy monetary policy, and that means the medicine is itself a risk for the patient.

Worried about China

Richardson is especially concerned about China.

“I would still say the next crisis is probably more likely to come out of China than anywhere else,” Richardson says. “If debt is vulnerability, the run up in debt in China is stunning.”

China, like Australia, sailed through the GFC on very low interest rates and a fat fiscal stimulus, but unlike Australia this fiscal stimulus was delivered partly via lending.

The GFC saw substantial Chinese financial system liberalisation, as Reserve Bank governor Philip Lowe explained in a speech in May 2018.

“[T]here was a very large lift in spending on infrastructure and construction. In other countries this might have been financed on the government’s balance sheet, but in China it was financed mainly through the financial system. The end result was a big increase in debt, with the ratio of debt to GDP rising significantly to its current level of around 260 per cent,” Lowe stated.

“One of these concerns is that during the big run up in debt, a lot of bad loans were made.”

That large volume of debt and high risk of bad debt would be a concern in any circumstance. Unfortunately, in China it is even more concerning, because China’s young financial system includes so much shadow banking – a byzantine mess of an estimated 3500 under-regulated small institutions. Clearing up such a network of bad debt is not as easy as saving one large investment bank.

Lowe is worried about China, and in his May speech laid his cards on the table.

“The experience is that the build-up of financial risks like those seen in China is almost always followed by a marked slowdown in GDP growth or a financial crisis,” he said.

Another financial crisis so soon on the heels of the last? It would almost be too much to bear. The good news is that China has the GFC to learn from. It knows the risks of debt build-up and the costs of financial collapse.

“Chinese authorities are now in a much more systematic and determined way dealing with the challenges they’ve got in the financial system,” Swan believes.

“They’ve spent years promising to do it [and] I think they are now actually doing it. And that’s a good thing. I don’t know that a Lehman Brothers [situation] would unfold in China the same way it would in America – they are unencumbered by democracy.”

But lessons learned cannot necessarily protect you from the infinite variety of risks in the world, as Deda points out.

“Given that we have had a GFC, the risk of that being repeated in the same way is lower than prior,” she says. “When we do get another economic crisis – and I’m not saying there will be one – it might be 10 years, 20 years, 50 years. But when a new one comes, I think it will be different in nature.”