Loading component...

At a glance

When the Reserve Bank of Australia (RBA) last changed interest rates Malcolm Turnbull was still prime minister, Donald Trump had yet to seize the White House, the UK had just voted for Brexit and house prices were booming.

During all the subsequent turbulence locally and abroad, the RBA cash rate has been a rare constant. In two and a half years it has not budged from a record-low 1.5 per cent.

However, markets and economists increasingly believe this period of policy stability is coming to an end, though views diverge sharply on whether the next move will be down or up.

The Reserve Bank recently indicated that it has shifted from a bias towards increasing interest rates to a more neutral stance. Governor Philip Lowe said in a recent speech that “over the past year, the next-move-is-up scenarios were more likely than the next-move-is-down scenarios. Today, the probabilities appear to be more evenly balanced.”

Unemployment falling

Some, such as CommSec senior economist Ryan Felsman and ANZ’s co-head of Australian economics, Cherelle Murphy, think the time is coming when the RBA will be able to raise interest rates.

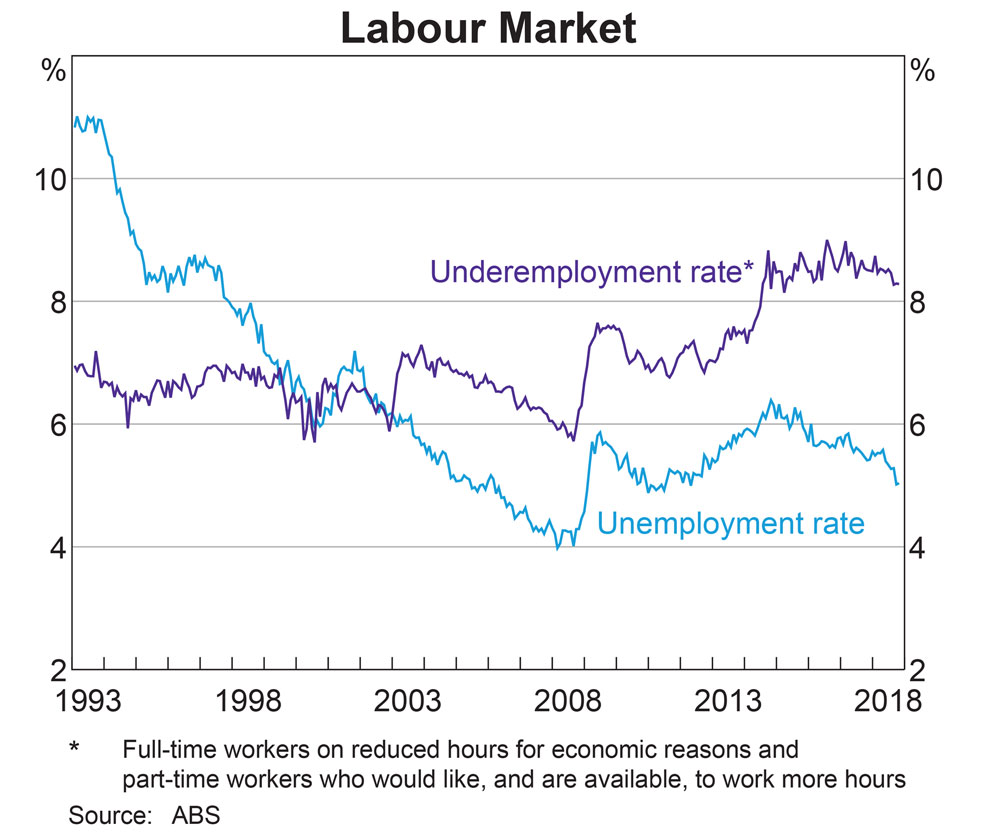

Despite weakening house prices, the employment rate was steady at 5.1 per cent in January, supported by strong participation in the labour force, according to the Australian Bureau of Statistics. The trend ratio of employment to population rose to a 10-year high of 62.4 per cent.

Felsman says the central bank will look past the continued slide in house prices and unexpectedly soft growth in the September quarter to developments in employment.

“The labour market is the key indicator going forward as far as interest rates are concerned,” he says.

Demand for workers has been building – about 284,000 jobs were created in 2018 and the unemployment rate has dipped to 5 per cent – and Felsman expects this pressure to gradually force wages higher and enable households to increase their spending.

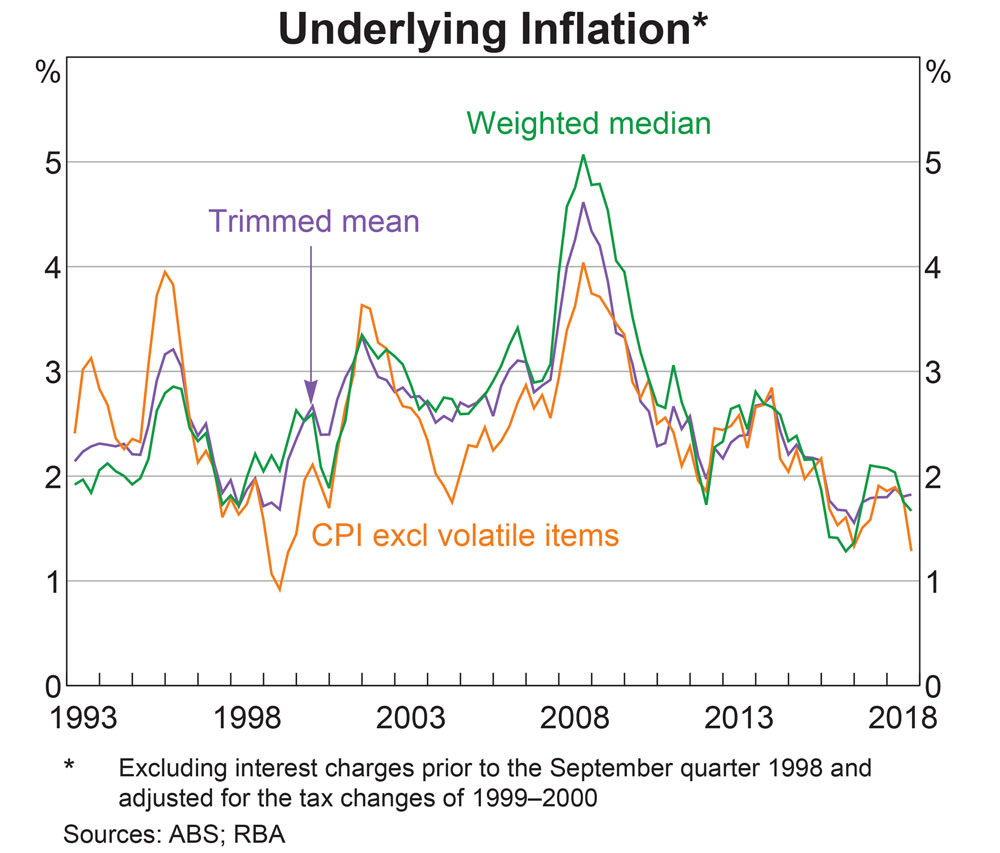

Eventually, he expects wages growth to reach 3.5 per cent, which would be consistent with an inflation rate of about 2.5 per cent – the mid-point of the Reserve Bank’s 2 to 3 per cent target band – “which the RBA has previously identified as a level they would like to get to before they lift interest rates”.

Interest rates to rise in November?

Felsman thinks this point will most likely be reached in November, convincing the central bank to lift the cash rate to 1.75 per cent.

Murphy shares Felsman’s upbeat outlook for the economy but foresees a more gradual improvement.

She does not expect the RBA to lift the cash rate until August next year, followed by another increase in November 2020 to take the cash rate to 2 per cent.

Murphy says national income is holding up. Businesses are being buoyed by good profits, encouraging them to invest and hire, and feeding more company taxes into government coffers.

Just as important, tighter credit conditions are working to cool the once-rampant property market without triggering widespread mortgage defaults.

While homeowners may see a peak-to-trough fall of 20 per cent in house values before the market stabilises, Murphy says the fact that mortgage rates are stable means few are being forced to sell.

“This helps explain why consumer confidence has not fallen in a hole, and instead has stayed at pretty high levels,” she says, along with the strong jobs growth.

Given the importance of private consumption for economic activity (accounting for almost 60 per cent of GDP), this is an important plus for growth.

Further interest rate cuts

AMP Capital Markets chief economist Shane Oliver and Market Economics principal Stephen Koukoulas are much gloomier about the economic outlook and believe tepid growth, elevated global risks and inflation that is stubbornly below target will leave the Reserve Bank board with no choice but to cut official interest rates in 2019. Oliver tips the rate to drop to 1 per cent by the end of this year; Koukoulas reckons it will hit a record low 0.75 per cent.

Both forecasts are more aggressive than financial market estimates which, which nonetheless have fully priced in a rate cut to 1.25 per cent by the end of the year.

Concerns about growth, falling house prices, stagnant wages and soft household spending have been underlined by the release of figures showing underlying inflation has been below the RBA’s 2 to 3 per cent target range for most of the past four years.

China’s slowing economy

Internationally, China – Australia’s largest export market – has slowed. In the 12 months to the December quarter it expanded by 6.4 per cent, its weakest pace in almost three decades as consumers eased the pedal on major purchases such as cars. The unresolved US-China trade war has deepened concerns about Chinese growth.

Against this, the Chinese Government has pledged to support the economy and is expected to unveil tax cuts and relax bank cash reserve requirements.

Nonetheless, the International Monetary Fund (IMF) expects the US economy to soften in the next two years as the effects of the Trump tax cuts fade, recent Federal Reserve rate hikes bear down on activity and the trade war with China rumbles on.

These developments are buffeting other economies. In Europe, the IMF expects Germany to be hit particularly hard. The euro zone’s largest economy is heavily reliant on exports to the US and China, and the Fund has sharply downgraded its growth prospects, forecasting it will expand by just 1.7 per cent this year.

Slowing European growth

Add to this mix the Brexit fiasco, and the IMF thinks the euro area as whole will struggle to grow by just 1.9 per cent in 2019 – and that is assuming Britain and the EU reach agreement on an orderly exit.

While these issues have been on the Reserve Bank board’s radar for some time, Oliver says the way they have evolved in the last few weeks will have it worried.

“I think they would be feeling more nervous about things than they were in December when they last met,” he says. “We have seen another round of volatility in markets, and a lot of the issues around that haven’t been resolved. Locally, the housing downturn has worsened, [and there are] more concerns about tight credit conditions.”

Despite this, Oliver does not expect the central bank to be in a rush to cut the cash rate and will instead want to see spending measures in the April Federal Budget and the promises made by both the major parties in the lead-up to the federal election before moving.

Amidst such uncertainty, the RBA and its counterparts around the world appear poised to act meeting to meeting, examining data in forensic detail for the faintest hints of how key aspects of the economy are faring.

As Felsman says, “Every policy meeting is now live.”