Loading component...

At a glance

- The value of the internet is difficult to assess, but economists believe its services are worth much more than the cost of internet subscriptions.

- It presents a significant consumer surplus, which is the gap between how much something is worth to us and how much we pay for it.

- Deeply ingrained in society, it is almost impossible to put a monetary value on the internet.

By David Walker

The internet became a global commercial network in the 1990s. Less than three decades later, it is everywhere. Now that we’ve created it and come to rely on it, we inevitably wonder: what is it worth?

This question turns out to be one of economics’ less easily answerable questions, but in trying to answer it, economists have shed light on the nature of both economics and our modern technological world.

What we're measuring

Economically speaking, the internet is odd. As an interconnected network (hence the name) of computers serving up information, it belongs to no one person. Arguably, a tiny share of it belongs to everyone who has access rights to space in any one of those computers, which is just about anyone with an email address, social media account or even a Wikipedia login.

Nicholas Gruen, Australia’s leading economic expert on the internet, calls it a “commons” – a term for resources that anyone in a society can access.

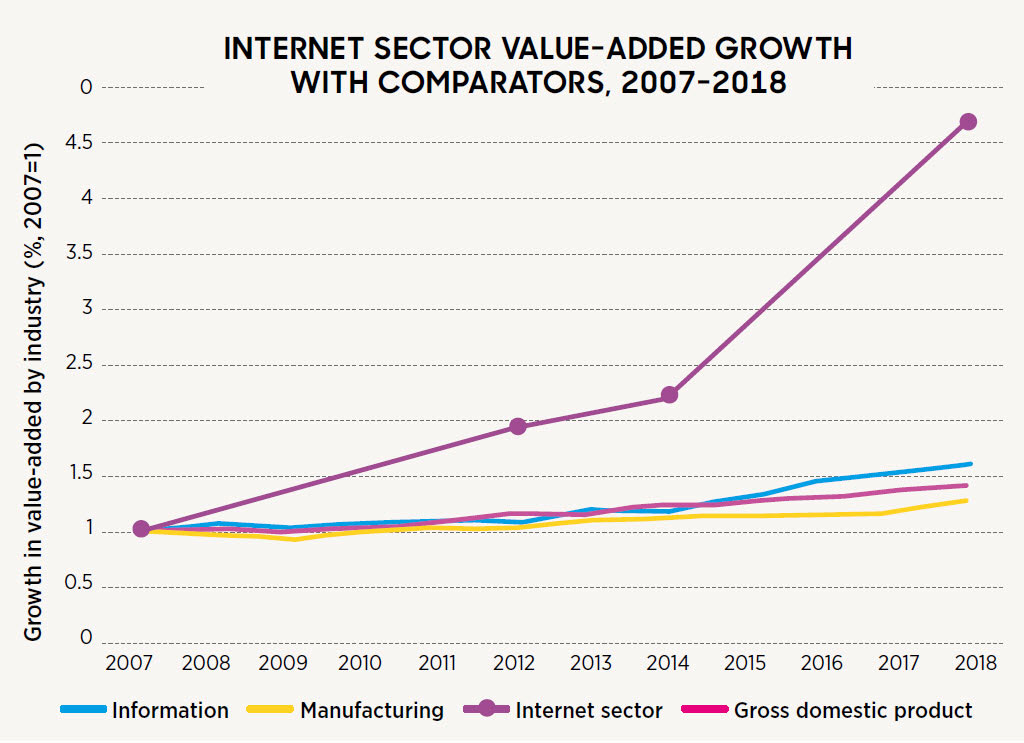

What we call the “internet industry” includes servers and cables and internet ads – everything from Google to your neighbourhood networking shop. A 2019 study for the Internet Association believed it to be worth US$2.1 trillion to the United States’ US$20.5 trillion yearly GDP.

Yet that number still seems too small. The world outside the internet industry uses the internet intensively – Uber, for example, or Spotify or, for that matter, us. The internet means much more than the people building and maintaining it.

Its greatest impact is almost certainly on ordinary people, working and relaxing, who browse the web for information, and to send emails, watch videos, post on Facebook and use maps in their cars. Most economists believe these services are worth far more than the price of our internet subscriptions.

This is where the real trouble begins.

Internet economy: The invisible surplus

“Consumer surplus” is economics’ term for a gap – the gap between how much something is worth to us, and how much we pay for it. Essentially, it’s the gift that the world economy hands us. Consumer surplus is everywhere, from that great sandwich you bought for A$10, but would have happily paid A$12 for, to the A$20,000 used car that has performed better than you ever expected.

A number of economists have noticed that for the internet, the size of that consumer surplus – that gift from the economy – seems substantial. Gruen’s response is typical: “My intuition tells me the consumer surplus is large,” he says.

The reason Gruen only has intuition to go off is because the consumer surplus is not captured in our economic data. Most of the information transmitted through the internet, in web pages and email messages, is free; there’s no price information.

Compared to the pre-internet world, this seems an enormous bargain. The documents we find in a web search; the detailed messages over email; the music on Spotify; the Wikipedia knowledge, more and better than that for which Encyclopaedia Britannica once charged hundreds of dollars – all free.

Economist David Henderson tells of realising how large a consumer surplus he was extracting from the internet when his email stopped working. The Apple Store fixed it in 20 minutes; the delighted Henderson estimated he would have paid US$500 to have it fixed right away rather than two weeks later. Trying to value the internet now is a little like trying to value electricity. Just as for Electricity, its removal would have consequences for the home, as well as in the workplace.

The trouble is that such moments of clarity are few and far between. For economists, that ubiquitous price – “FREE!” – makes the internet’s value even tougher to assess.

If you just ask people how much they value the internet, you’ll get some big and strange responses. Even if you ask people how much money they would need to compensate them for the loss of the internet, the responses may not make that much sense. How does a newspaper journalist, for instance, calculate both the ease of accessing information and the cost of the shrunken market for their services in the internet era? A person at one desk may curse the internet, while the person at the next desk celebrates it.

The problem gets worse when we remind ourselves that if we had not been online, we would have been doing something else. As economists such as the US-based Technology Policy Institute’s Scott Wallsten have pointed out, the value of the internet is not the value of what we do on it, or even the value of the consumer surplus it generates. It’s the value that we get from it over and above what we would have got from whatever we would have done if it had never existed.

That gap is really hard to quantify. If the internet didn’t exist, you might have been chatting with friends last night instead of watching that YouTube video. How much worse would that have been? It’s hard to tell. If the internet has some unhealthy addictive qualities, the chat could even have been a better option.

Accounting for the internet economy

In 2005, two economists, Austan Goolsbee and Peter Klenow, tried to do the sums for non-work internet use. They argued that the time someone spent online said much more about how they valued the internet than what they paid for it. At the time, just 0.2 per cent of US consumers’ spending went to internet access, yet consumers spent about 10 per cent of their leisure time online.

Goolsbee and Klenow came up with a value for annual non-work US internet use of between US$2500 and US$3800 per person – about 2 per cent of income. However, as they admitted, their number had some problems.

One was that they couldn’t account for how much better the internet was compared to whatever it had replaced for individuals. If everyone in 2004 valued the internet as just a tiny fraction more worthwhile than watching the new TV show The Apprentice with Donald Trump, then the internet’s consumer surplus was probably less than they’d estimated. Alternatively, it could be even greater than their number.

Two other economists, Shane Greenstein and Ryan McDevitt, adopted a different technique to estimate at least part of the internet’s consumer surplus: calculating what people were willing to pay for it through access fees. As fees fell over time, their consumer surplus got bigger and bigger.

They calculated broadband delivery of internet services in the US was each year generating US$39 billion of revenue and up to US$7 billion of consumer surplus – closer to US$25 a person than US$2500.

However, as Greenstein and McDevitt acknowledged, that method too was flawed: it estimated just a slice of the internet’s value, and it didn’t take into account any improvements in the internet’s services, such as Google or Facebook.

Most recently, yet more economists – this time Erik Brynjolfsson, Avanish Collis and Felix Eggers – tried yet another tack: in 2017, they asked people already on the internet whether they would give up a particular internet service in return for money.

On average, respondents said they would forgo services such as search engines for US$17,530, email for US$8414 and maps for US$3648.

This study tells us a lot about what people value most about the internet. It also gives us a figure for internet consumer surplus across the US: almost US$8 trillion a year in an economy with a US$20.5 trillion economy.

Why valuing the internet doesn't work

Gruen is writing a book on the internet and society, and he doesn’t trust any of these numbers. For a start, all of them leave out too many unknowns.

More importantly, though, he thinks the question no longer makes sense.

Gruen sees the internet as what economists call a general-purpose technology. In 2019, it is “baked into everything”, he says. Civilisation wouldn’t collapse without it – after all, 25 years ago we were getting on just fine with no public internet to speak of. Yet much of society would have to change how it worked. His ultimate conclusion: we can no longer meaningfully value the internet at all.

Greenstein, after turning it over in his mind, agrees. Trying to value the internet is now a little like trying to value electricity. Just as for electricity, its removal would have consequences for the home, as well as in the workplace. Like electricity, the internet has not only raised productivity, but also transformed leisure.

Today’s younger generations “consume their entertainment through their tablets and telephones”, he notes.

Indeed, a real-world example now shows what happens when you remove internet access. India’s government turned off internet access in Muslim majority Kashmir in August 2019 in a bid to reduce public protest. The effect even in this poor region was immediate: pharmacies quickly began to run out of medicine; students could not study; news about the region dried up, even within the region itself. The New York Times quoted one local as saying: “There is no life without internet, even in Kashmir.”

At this point, Greenstein says, valuing the internet is a task for which economics lacks the tools.

“It’s no longer a partial equilibrium,” he explains. Or in plainer English: “It’s not a well-grounded question anymore.”

The internet, it seems, is now too deeply ingrained in our society to be assessed with mere money.