Loading component...

At a glance

- Australia’s employers appear unfazed by slower national economic activity, adding 51,000 extra workers in the first two months of 2019.

Unemployment fell to a 30-year low of 3.9 per cent in late 2018, but rose to 4.3 per cent in February 2019.

Some economists believe the rate could reach as low as 4.5 per cent before levelling off, driven by a potential pick-up in investment.

Around the world governments and central banks are taking the red pen to growth forecasts as economic headwinds intensify.

The International Monetary Fund has trimmed its expectations of global economic growth to 3.3 per cent amid unresolved US-China trade tensions, the running sore of Brexit, and disruptions to Germany’s auto industry.

In Australia, sliding house prices, subdued wages and the possible escalation of the US China trade conflict have heightened what Treasury calls “downside risks” to growth.

However, so far, Australia’s employers appear unfazed.

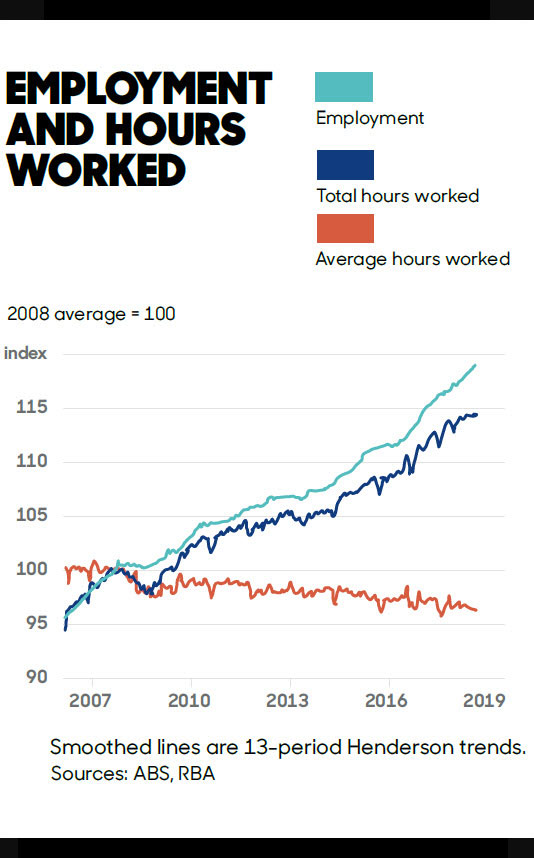

Shrugging off a slowdown in national economic activity, a weakening property market and continuing concerns about the global economy, employers recruited an extra 51,000 workers in the first two months of 2019, pushing unemployment down to 4.9 per cent, its lowest point in almost eight years.

The labour market in some of the nation’s most populous states is even tighter. In New South Wales, unemployment fell to a 30-year low of 3.9 per cent late last year before edging up to 4.3 per cent in February, while in Victoria it sits at 4.8 per cent.

This can partly be put down to time lags. Many people who started work in early 2019 were recruited late last year, when employers were feeling more confident about their prospects.

There are increasing signs that Australian businesses are starting to respond to the gloomier outlook.

Just a net 4600 people entered employment in February, down from more than 39,000 in January and 21,600 in December. Reflecting this, the employment-to-population ratio, which reached a record 62.4 per cent in January, slid 0.1 of a percentage point lower the following month.

No vacancy?

Although economists caution against reading too much into monthly moves in employment data, Westpac senior economist Justin Smirk says the data indicates the labour market is losing momentum.

He believes the current slowdown in housing construction and the May election result will weigh on investment and hiring in coming months, driving unemployment up to 5.5 per cent by the end of 2019, and even higher in 2020.

His concerns are supported by the National Australia Bank (NAB) Monthly Business Survey, which suggests forward orders and capacity utilisation have been trending lower in recent months. NAB group chief economist Alan Oster warns of rising risks to business investment, which could challenge job growth. CPA Australia’s annual Asia-Pacific Small Business Survey points to a slower economy, with the number of Australian small businesses expecting to grow in 2019 at 47.3 per cent, down from 55.6 per cent in 2018.

Further, only 14.5 per cent of Australian small businesses expect to add to their headcount in 2019, the lowest number since 2014, and well below the survey average of 41.2 per cent.

These concerns are also borne out by the ANZ Bank’s Australian Job Advertisements index, which in March had declined for four consecutive months to be down 4.3 per cent from a year earlier. Others are less pessimistic than Smirk and expect any slowdown in the labour market to be contained.

CommSec chief economist Craig James anticipates the jobless rate has further to fall and may reach as low as 4.5 per cent before levelling off, driven primarily by a pick-up in investment.

After years of focus on cutting costs and returning money to shareholders via dividends and share buy-backs, James says there are signs that companies outside the mining sector are dusting off investment plans.

In its regular survey of businesses, the Australian Bureau of Statistics has found capital expenditure in 2018-19 is up 3.6 per cent from the previous year, and investment plans for the next financial year are 11 per cent bigger than they were the same time last year.

BIS Oxford Economics’ chief Australia economist Sarah Hunter says this bodes well for jobs. “Non-mining investment was very weak during the mining boom,” she says.

“But it has turned the corner and we should see some catch-up, and that goes almost hand-in-hand with the labour market improvement.”

Treasury expects sufficient non-mining investment to support a 1.75 per cent lift in jobs next financial year, enough to hold the unemployment rate at 5 per cent.

James argues the jobs market may be even tighter than traditional measures such as the unemployment rate suggest.

He says the apparent disconnect between the strong labour market and an economy seemingly losing momentum may be partly down to shortcomings in the way these things are measured, particularly when it comes to capturing activity in the gig economy.

In the past five years, about 24,000 new transport service businesses (such as Uber) and about 23,000 accommodation services (think Airbnb) have been created, as well as other home-based service businesses, he says.

“If the Australian Bureau of Statistics is still looking at things in the traditional mode, rather than looking at the new businesses that are setting themselves up in the cloud or in non-traditional areas like the home, perhaps they are not capturing the full output from the economy,” James says.

Capturing the impact of innovations like smartphones and social media may be even more problematic.

Hunter says such developments have transformed how people operate in ways that are not being captured in the data.

For instance, inflation figures do not take accurate account of changes in quality.

“Just think of mobile phones,” says Hunter. “Phones 10 years ago are like night and day to phones today but are still counted as mobile phones [in the data]”.

Show us the money

Even if the economy is holding up better than the numbers suggest, it is yet to show up in workers’ pay packets. Since 2015, nominal wages have increased by an average of just 2 per cent a year – half the pace of the past 50 years and the weakest gain since World War II.

The unusual confluence of solid growth and stagnant wages has economists scrambling for answers. According to the time-honoured Phillips Curve, there is an inverse relationship between unemployment and inflation – as the former falls, the latter rises.

It held sway as recently as 2008, when the unemployment rate fell well below 5 per cent, convincing the Reserve Bank of Australia (RBA) to yank hard on the interest rate lever in order to head off an inflationary wages-price spiral.

Ten years later and the picture could not be more different. Although the unemployment rate has again fallen below 5 per cent, inflation is seemingly anchored below 2 per cent and official interest rates are at a record low 1.5 per cent, with expectations that they could go even lower. It is a similar situation across most advanced economies, prompting speculation that the Phillips Curve is dead.

However, leading thinkers such as Bank of England chief economist Andy Haldane argue, like BIS Oxford’s Hunter, that it still has a pulse, but is now operating in a significantly different environment.

An important structural change, Hunter says, has been a material decline in inflation and inflation expectations. Because workers are primarily interested in purchasing power rather than the rate of pay per se, wage increases are typically aligned with actual or expected increases in living costs, plus a component for improved productivity.

The main inflation measure, the consumer price index, has been trending down since the mid-1970s, and particularly since the RBA gained statutory independence in the early 1990s.

This has been accompanied by a steady moderation in consumer inflation expectations, to the point where the mean is anchored at about 2.5 per cent – the midpoint of the RBA’s 2 per cent to 3 per cent inflation target band.

“If you have got this materially lower pace of inflation, that then feeds back into a lower starting point for any wage negotiation,” Hunter says.

The hand that is dealt

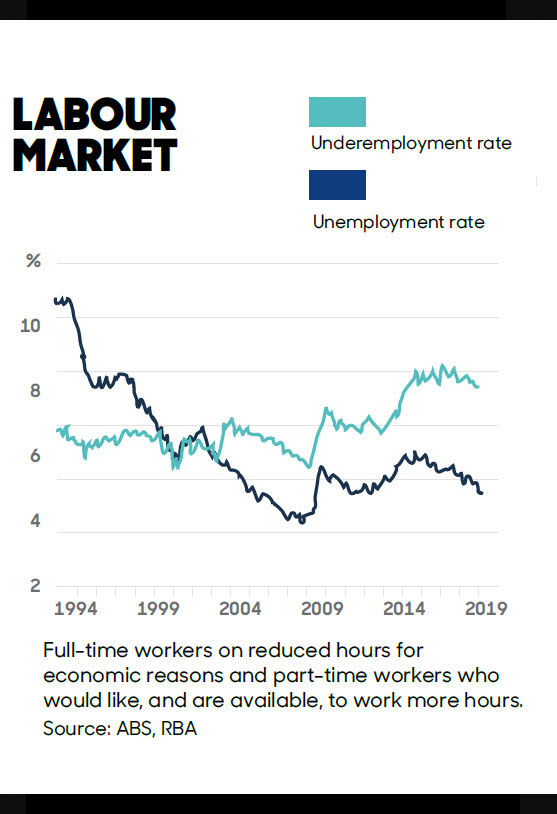

To top it off, the bargaining position of workers is not as strong as the low unemployment rate suggests.

Although 12.7 million Australians have a job, more than a million (8.1 per cent) complain they are underemployed and would like to work more hours. This means that there is much more slack in the labour market than the jobless figure suggests, and the competition for workers outside some specialised areas is not as intense as might otherwise be the case.

Smirk says the ability of workers to negotiate for pay increases has been further blunted by 20 years of workforce deregulation and waning union membership – a situation not helped by the increasing casualisation and outsourcing of work in many sectors.

One of the most important changes, the Westpac economist says, has been the mass entry of women into the labour force, which has helped push the participation rate up to historically high levels, close to 66 per cent despite the gradual ageing of the population.

This has coincided with a shift in the structure of the economy away from manufacturing and construction to an increasing preponderance of service jobs.

The female-heavy healthcare and social assistance industry is the fastest-growing sector of the economy in the past five years, and employs more than 1.5 million people.

Education, training and hospitality are also growing strongly.

However, while these sectors are big employers, they tend to provide lower wages, which is helping to hold income growth back, Smirk says.

Typically, services also record lower rates of productivity improvement, further undermining the case for bigger pay packets.

Reassuringly for households and growth, economists forecast the phase of stagnant incomes will pass.

Smirk says the supply of women entering the workforce will eventually reach equilibrium and the pool of underemployed workers will shrink. In this, he expects the state of Victoria to lead the way, and predicts wages there to pick up in the next year or two.

However, the days of 4 per cent-plus pay increases are probably gone, warns James. Instead, with inflation stuck at about the 2 per cent mark, workers should expect wages to increase by about 3 per cent on average, giving them a small 1 per cent real gain in purchasing power.

“If that’s the end outcome and becomes sustainable, then people will get used to that fact and not be as downbeat as they are now that this is the new reality,” he says.

Expect to see a lot more people driving Ubers or renting out rooms on Airbnb.

The picture in Asia: slow pay growth

The world’s lowest unemployment rate of 4.1 per cent hasn’t been enough to shield workers in the Asia-Pacific from weak global wage growth.

According to the International Labour Organization (ILO), pay growth has slowed sharply in South-East Asia and the Pacific in recent years, from 8.4 per cent in 2016 to 2.4 per cent in 2017, and the weakness is expected to persist this year.

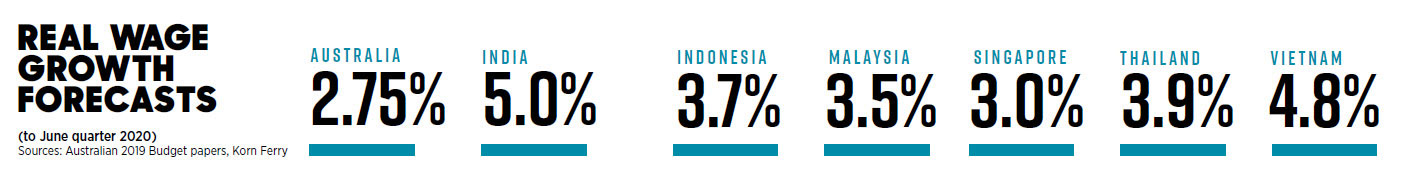

Management consultant Korn Ferry predicts real wages in some of the region’s most dynamic economies will soften in 2019, at an average gain of 5 per cent in India, 4.8 per cent in Vietnam, 3.9 per cent in Thailand, 3.7 per cent in Indonesia, 3.5 per cent in Malaysia and 3 per cent in Singapore.

While workers in Australia and other advanced economies would look at such pay gains with envy, they are lacklustre for countries whose economies are still in transition.

Economist Vishnu Varathan, head of economics and strategy, Oceania and Treasury Department at Mizuho Bank, says governments and analysts around the region are puzzled by why this is occurring. A big part of the explanation seems to be the structure of labour markets in the region.

Countries such as India and Indonesia have huge informal sectors, Varathan says, and aggregate labour force data obscures huge discrepancies in wages and job security.

The ILO says almost half of workers in the Asia-Pacific are in precarious or low-paid jobs, with a quarter living in moderate or extreme poverty.

“Many people still have no choice but to take jobs with poor working conditions that do not generate stable incomes or safeguard them and their families against poverty,” says Sara Elder, head of the ILO’s Regional Economic and Social Analysis Unit.

In many countries in the region, jobs are moving from agriculture into other sectors, primarily services, and Varathan says often workers struggle with the transition, fuelling youth unemployment and exacerbating rural-urban pay gaps.

Anthony Dass, chief economist at AmBank, says the plight of young job seekers in Malaysia is worsened by the reluctance of many firms to invest in innovation and growth.

He says most jobs being created are low and mid-skill because local industries remain focused on low value added activities that rely on cost efficiency and cheap labour to stay competitive.

Compounding the inequality is the relatively low participation rate of women in the region’s labour force.

Women comprise 700 million out of 1.9 billion workers in the Asia-Pacific. Their participation rate is 30 percentage points lower than that of men and has barely shifted since 2000, according to the ILO.

However, Varathan is hopeful that conditions in the region’s labour market will improve. An upswing in government spending in places such as India and Indonesia will boost infrastructure and construction activity, he says, while more factories are being set up in Vietnam, Thailand and the Philippines.

As the region’s middle class emerges, the demand for services will build, and the quality of jobs should lift.