Loading component...

At a glance

In the notoriously fickle farming business, just a change in the weather can make the difference between bumper profits and devastating losses. In this context, the decision of some of Australia’s largest institutional investors to sell off their joint farm investment, the Sustainable Agriculture Fund, earlier this year, seems inspired.

Just months after it was put on the market, the venture revealed an 18.7 per cent return on investment for 2016-17 – the fourth consecutive year net cash profit has increased.

Interest from potential buyers has, unsurprisingly, been strong, and the cornerstone investors, including AustralianSuper, Catholic Super, AMP Capital and Christian Super, appear set to make a tidy sum on the deal.

However, not all forays by institutional investors into agriculture end so well. Stephen Anthony, chief economist at Industry Super Australia, says institutional investments in farms have a chequered history.

While some investments have performed well, others with volatile rates of return and high fixed costs have tested investor patience, often resulting in high-quality farming assets being sold off to private interests “for a song”, he says.

“There have been at least seven major attempts by Australian superannuation funds to operationalise large-scale agricultural investments,” Anthony adds. “None of them have been major success stories – not, at least, so far.”

The Prudential Agricultural Fund, for instance, which owned cattle stations across northern Australia, was liquidated in the early 2000s following uneven returns. In 1996, National Mutual sold its A$200 million portfolio of farms amid concerns about financial performance.

Although many institutions, including AustralianSuper, First State Super, UniSuper, the Retail Employees Superannuation Trust, VicSuper and Macquarie (through the Macquarie Pastoral Fund and Macquarie Crop Partners) have investments in Australian agriculture, their exposure is small.

Anthony estimates industry super funds together hold just A$1.56 billion in farming assets, which amounts to less than 0.3 per cent of their total funds under management.

“There is a general consensus that Australian super funds have tended to underinvest in agriculture in Australia,” Anthony says, particularly among retail funds.

This underinvestment is all the more striking given the size of Australia’s farming exports and excitement about its prospects for growth, servicing booming demand for food in East Asia.

A billion mouths to feed

Although agriculture is dwarfed by other sectors of the Australian economy – its share of gross domestic product is just 2.2 per cent, compared with services (61 per cent), construction (8 per cent) and manufacturing (6 per cent) according to the Office of the Chief Economist’s Australian Industry Report 2016 – it contributes more than 10 per cent of the national export total. In the 2015-2016 financial year, Australia sold more than A$46 billion worth of beef, wheat, wine, wool, cotton, dairy and other farm products to the world.

The rapid emergence of an Asian middle class is seen as an opportunity for growth, with the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development estimating that Asia will be home to two-thirds of the world’s middle class by 2030. That will bring an increased appetite for meat, seafood and other high-quality foodstuffs. As a consequence, food demand is expected to jump by 50 per cent in the next 15 years.

Already, offshore investors have identified the potential and are building considerable stakes in Australian farms and agribusinesses.

In northern Australia, for instance, the privately owned Shanghai Zhongfu Group has, through its wholly-owned subsidiary Kimberley Agricultural Investment, bought and leased about 500,000 hectares of farmland in the East Kimberley, including the massive 476,000-hectare Carlton Hill cattle station.

When the iconic Kidman cattle empire – consisting of 100,000 square kilometres of pastoral leases and 185,000 head of cattle – went on sale in 2016 it sparked a frenzy of interest from buyers around the world before it was snapped up by mining and farming magnate Gina Rinehart, in partnership with Chinese real estate conglomerate Shanghai CRED.

Foreign investors are also big players in the processing of food and agriculture products. Japanese-owned Lion (a A$5.6 billion food and beverage producer), Brazil’s JBS (which owns and operates 10 meat processing plants and five feedlots in Australia), Swiss giants Nestlé and Glencore AG, Singapore-based Goodman Fielder and Olam International, US-owned companies Cargill and Inghams and French-owned Italian company Parmalat are all major players in Australia’s agribusiness industry.

Foreign interests moving in

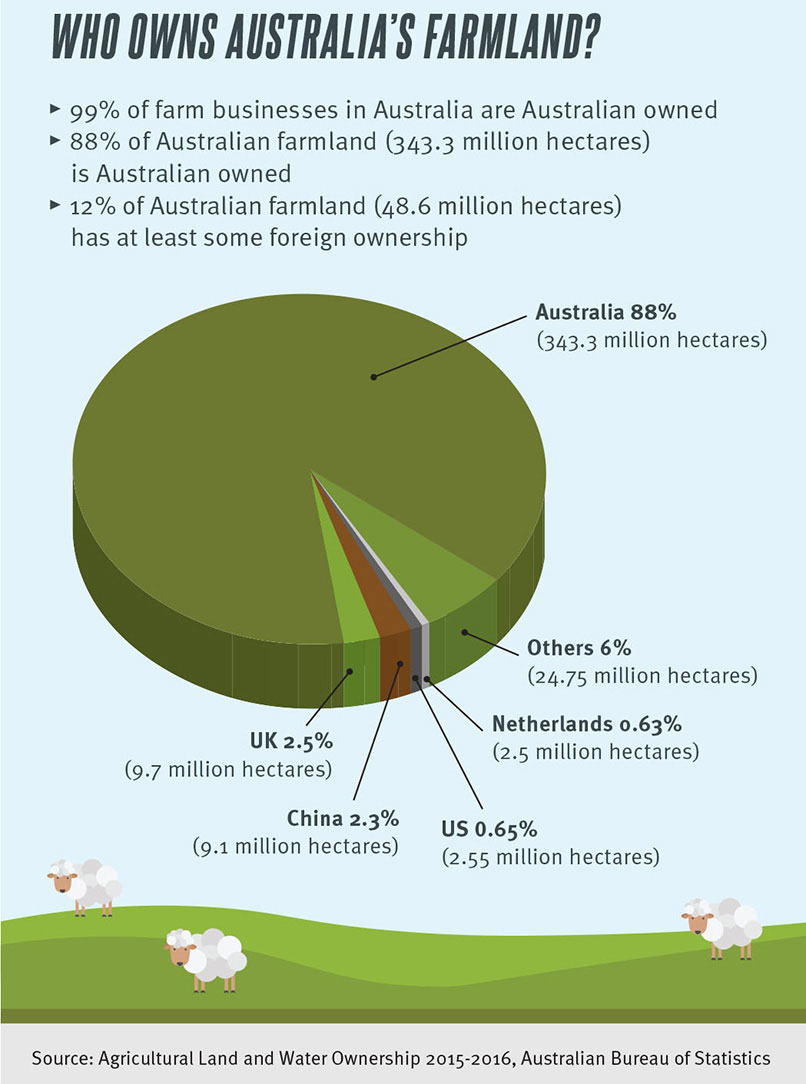

Fears that foreigners, particularly the Chinese, are buying up Australian farms so fast that few will be left in local hands are overblown. In its June 2017 audit of foreign farm ownership, the Australian Taxation Office found just 13.6 per cent of agricultural land is in foreign hands. The Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS) quotes an even lower figure: it estimates 12 per cent of farmland is owned by foreigners.

The British are the biggest foreign landholders, holding more than 9.7 million hectares, but the Chinese come a close second, after the massive S. Kidman & Co sale pushed their total holdings to 9.1 million hectares. US investors own 2.55 million hectares.

The rapid increase in Chinese land ownership has turned foreign investment in Australian agriculture into a political issue, with calls for greater government scrutiny of purchases.

David Irvine, chair of the Foreign Investment Review Board, says that despite community agitation, foreign ownership of Australian farms has increased only marginally in recent years.

To underline the point, of the 134,000 farm businesses in Australia, 99 per cent are Australian owned, according to the National Farmers’ Federation.

Anthony warns the current picture is set to change as foreign institutional investors increasingly eye off opportunities.

“It is very clear that big North American pension funds are moving into Australia looking for prime agricultural investments.

“They’re likely to be expanding their operations over the next decade and, in addition to that, there is much more interest from Asian investors, especially from China, India and Korea.”

Getting information out to market

Puzzled by the reluctance of most local institutional investors to buy into farming, Anthony has identified what he thinks are important barriers blocking further investment.

For many funds, he says, the tough and volatile nature of Australian farming (think climate change and prolonged droughts) is off-putting, the scale of investment required is too large, and the hybrid nature of agricultural assets (which have the characteristics of both property and infrastructure investments) makes them too difficult to assess and manage.

However the major constraint, Anthony says, is that investors do not have access to the information they need – something he thinks accountants are ideally placed to help address.

“The key thing is the quality of information hitting the market,” he explains. “It is about taking a common standard for reporting performance based on common financial principles and applying that across the sector, across different commodities, and getting that information out to the market.

“If we can apply existing standards and get audit-quality information to the market on those unlisted assets, we then empower fund trustees and other decision-makers to make robust decisions with high confidence.

“In this process, CPAs have an enormous role to play in terms of guiding rigorous decision-making.”

Harvesting agency data for agriculture

Economist Saul Eslake has a very different view of the data available to institutional investors. He says agencies such as the Australian Bureau of Agricultural and Resource Economics and Sciences (ABARES) and the ABS publish a lot of data on the financial performance of farms, including financial returns and yields, which can be used as benchmarks by investors.

While these agencies do not report on the performance of specific farms, the information they publish is detailed enough for potential investors to assess how a farm business is performing compared with its peers, he says.

The Sustainable Agriculture Fund, for instance, used ABARES modelling to help build its portfolio of beef, dairy and crop farms.

Eslake is similarly sceptical of the idea that institutional investors are deterred by the volatile nature of farming investments.

“It is true that it [farming] is incredibly volatile,” he says, but “volatility on its own hasn’t necessarily been a deterrent to institutional investors. Often they deliberately buy volatility; that is why they buy options.

“I suspect that [volatility] is more an excuse than a reason.”

Eslake thinks the factor discouraging investment is concern about the liquidity of agricultural assets.

“For the same reason they are often hesitant to invest in infrastructure assets, small- and medium-sized institutional investors have a concern that if for some reason they need to shift their portfolio around fairly quickly, there is not necessarily a ready market in which they can liquidate their investment in a farm,” he says. “That is why they tend to stick to listed equities.”

Keeping it in the farming family

Eslake says institutional investors also face resistance from farmers themselves. While farmers are prepared to borrow, often heavily, they are far more reluctant to share the equity and ownership rights that accepting investment from an institutional investment would typically involve, he says.

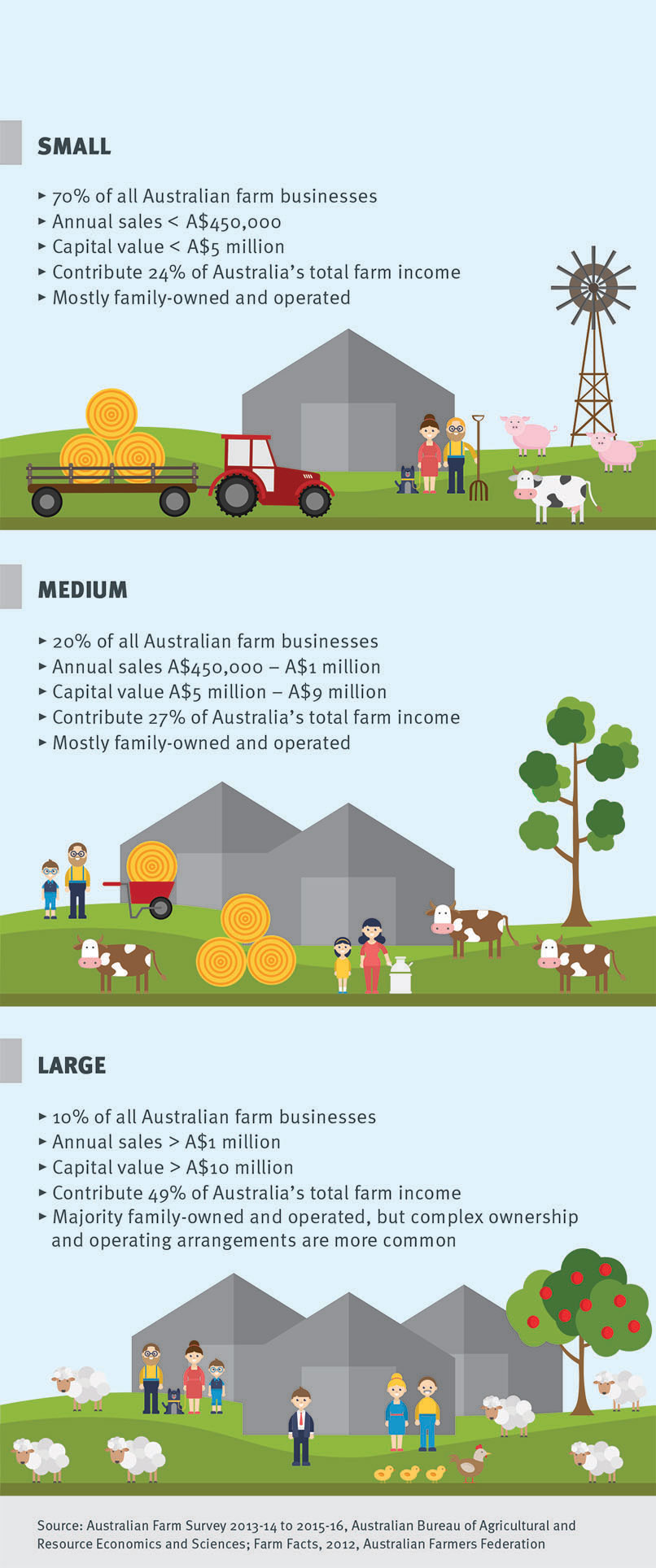

Survey work by ABARES bears this out; its Australian Farm Survey Results 2013–14 to 2015–16 shows that the equity ratio of the vast majority of farms is well above 90 per cent.

“I have done a lot of work with farmers, and the question [of institutional investment] comes up a lot,” says Eslake.

“Farmers raise concerns about foreigners buying up agricultural farmland and say, ‘[Australia has] A$3 trillion or whatever it is in superannuation savings; how come that is not invested in agriculture?’.

“I ask them, ‘Are you prepared to sell 40 per cent interest in your farm and give someone else a say in how you run it?’ Few do when it is put to them like that.”

Eslake says there is a strong ethos in family farming that the farmer needs to own the land and the machinery and equipment that is used.

“It means that farming can be very intensive in its use of capital in ways that make sense to the individual farmer but do not make a lot of sense to an institutional investor,” he says.

Feeding the need for food for Asia's middle class

To make the most of the opportunities presented by Asia’s emerging middle class, ABARES and the ANZ Banking Group assert it is feasible for Australia to aim to increase the value of food exports by 140 per cent (from 2007 figures) by 2050.

However, to achieve that will require major investment to open up more land to production, including through greater irrigation, as well as more intensive use of fertilisers and other chemicals, research to increase the productivity of crops and livestock, and improvements in transport networks and other infrastructure.

In its Greener Pastures report from 2012, ANZ stated that an extra A$1 trillion of investment in agriculture would be needed up to 2050.

As Irvine notes, Australia is likely to need to draw on both domestic and foreign sources of investment if it is to have a hope of reaching such a target.

“As a large, resource-rich country with relatively high demand for capital, Australia has relied on foreign investment to meet the shortfall of domestic savings against domestic investment needs for over two centuries … While Australia’s institutions will play an important role in providing that capital, foreign capital will also need to play a vital role,” Irvine says.

To ease the way for domestic investors, Anthony suggests a statistically robust survey of farm performance, possibly funded by a levy on producers, as well as an audit of transport and grain-handling infrastructure, greater transparency in wholesale agricultural markets, the establishment of a rural and regional development bank to support long-term investments by rural producers, and “a more strategic approach to foreign investment from Treasury to ensure core assets are not being dealt away to foreign investors.”

Eslake says the stakes are high, and worries that the current hostility towards large-scale foreign investment in Australian farming makes the country dangerously reliant on domestic institutional investors.

“If we don’t find a way to increase investment from institutional investors, then it won’t happen at all and the country will forgo the opportunities that are out there.”

With Asia’s growing middle class developing a taste for Australian products, the prospects for the agricultural sector should be bright. However, it will take investment – including foreign investment – for Australia’s farmers to realise that potential.