Loading component...

At a glance

- Forensic accountants assist in investigations across numerous cases, including money laundering, proceeds of crime, fraud and embezzlement.

- Court appearances are an important part of forensic accounting, and the accountant must be skilled in explaining their evidence-gathering to a judge or jury.

- Far from being purely technical, forensic accounting demands a suite of interpersonal skills, especially strong communication and teamwork.

By Johanna Leggatt

Retired forensic accountant Terence Brooks FCPA regularly talks to students about the machinations of forensic accounting, and, in his view, crime scene investigation-style TV programs have a lot to answer for.

“If I talk to younger people, they often have an unrealistic view of what the job is,” he says with a laugh.

“Once, when talking to high school students in regional Victoria, one student told me that forensics is dealing with dead bodies.”

Needless to say, Brooks and his compatriots don’t deal with deceased victims, but you could argue they’re working at the cutting edge of the accounting world.

Manager of the forensic accounting unit for the Financial Crimes Squad, State Crime Command at New South Wales Police, Ana Ferrol FCPA, says forensics is often viewed as the “sexy part of accounting”.

“For me, I love it because it’s always changing, no two days are the same,” she says, “and it’s rewarding to help compile the data that assists police in securing convictions.”

For Brooks, who set up the Forensic Investigations Unit of The Professional Standards Command at Victoria Police before retiring last year, the rewards of a career in forensics are many and varied. “I love, especially, that you work backwards,” he says.

“Accountants traditionally take data and build it up into ledgers and statements, but with forensics you start from the data and work backwards.”

All in a forensic accountant's day's work

According to Ferrol and Brooks, forensic accountants working in the criminal sphere assist police officers with their investigations across numerous cases, including money laundering, proceeds of crime, fraud and embezzlement.

“Our work could involve even homicide or arson cases, where financial documents are relevant to the case,” says Ferrol.

During his time at Victoria Police, Brooks worked on fraud cases, drug dealing allegations involving proceeds of crime evidence, and a missing person case. “A lot of what we do is what I call looking at the nexus between time and place,” says Brooks.

“The analysis of bank accounts that were used at a particular place and time, for example, can be a form of evidence.”

Far from being confined to criminal investigations, the bulk of forensic work is done by civil investigators, explains Brooks.

He notes while his remit was strictly criminal, forensic accounting extends to family law, civil disputes, loss and damages, and fraud prevention.

Boyd Harris CPA works at forensic accounting firm Axiom Forensics, which is primarily dedicated to litigation support, including providing expert reports, witness testimony and consulting work.

“We do a little bit of criminal work, but the bulk is civil litigation,” says Harris.

Generally, the work arrives via lawyers, government departments or class actions. Frequently they handle lawsuits between companies, with claims in the tens of millions, Harris notes.

“Out of all the cases I work on, there are probably 10 or 20 per cent that go to trial. Most of the time it will go to mediation or settle beforehand,” he says.

See you in court

Nevertheless, court appearances are an important part of forensic accounting, and the accountant must be skilled in explaining their evidence-gathering to a judge or jury.

Ferrol points out that all of her team members are required to give evidence in court, for which strong written and oral communication skills are paramount.

“They also need to be able to relay their findings in a way that their audience can understand in layman’s terms,” she says.

“Especially when you’re providing oral evidence in a court and you have 12 jury members who are not accountants.”

Brooks says forensic accountants must master the evidence and data before they enter the courtroom, and then parlay that into a concise, well-worded report.

“When you are in court – and I have had this many times – you will be crossexamined by the defence who will seek to expose any weaknesses or inconsistencies in your report,” he says.

“So you have to master your information and be very clear and confident about it.”

If there are areas where you don’t have total confidence, you need to declare it to the court, while also withstanding any pressure from clients to present the material in a certain way, says Brooks.

You may be dealing with a client, for example, who may have suffered a loss or injury, but at the end of the day, says Brooks, “if you’re in court, you’re no longer employed by your client, you become a servant of the court”.

“I’ve had clients who may not have been happy with my findings because they’re emotionally invested in the case,” says Brooks.

The message is that court plays a role in forensic accounting and for that reason alone, it may not be for everyone.

“I’ve appeared in court many times in my career and it’s a very serious undertaking and it never gets easy.”

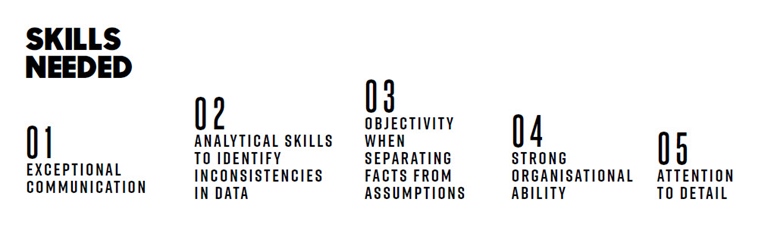

Soft skills are crucial – and these are the top 5

Far from being a purely technical field, forensic accounting demands a suite of interpersonal skills, especially strong communication.

“In terms of personal attributes, you have to have an enquiring mind and high levels of analytical skill to analyse data,” Brooks says.

Interpersonal skills are another must. “If you’re involved in interviewing or investigations, you have to be able to know what you’re looking for and exercise a high level of ability when interviewing people and getting the information you need.”

Ferrol says an eye for the hidden detail is hugely important. “You need to be a very detail-orientated person because you are reviewing voluminous financial documents, so you need that eye to identify discrepancies,” she says.

Being a good team player and being able to work under pressure help, too.

“My team is working on an average of 10 cases at once, and they’re complicated cases,” says Ferrol.

Later-life switch?

It is possible to move to forensics mid-career, but Ferrol warns you may earn less in the short term while you upskill.

“My mid-level and senior team members mentor and supervise the junior team, so there needs to be extensive knowledge of forensics at the mid-year levels and up,” she says. “It depends on the person. The accountant may be willing to take a step backwards into forensics to move forward.”

Harris made the mid-career switch to forensics nine years ago, and hasn’t looked back.

“I previously worked as a financial controller, but I always found that the part of the job I enjoyed most was fixing everything up,” he says.

Harris says a lot of the accountants who have crossed to forensics mid-career have tended to come via the established pathways of insolvency or audit.

“We do employ junior staff straight out of university and we have some interns coming through here pretty regularly,” he says, “but a lot of people who end up in forensics have spent time in either insolvency or audit.”

Harris points out that the valuation and letter-writing side of insolvency work and the more investigative aspect of auditing complement the forensic skill set.

There are also plenty of career options for senior forensic accountants who wish to branch out, as McCormack can attest.

McCormack works two days a week for the Sydney campus of the University of the Sunshine Coast, where she teaches corporate reporting and audit as part of the bachelor of accounting and masters of professional accounting degrees.

She also works as a consultant for medium-sized businesses. In 2014, McCormack completed her PhD in forensic accounting, where she developed an online role-play to teach auditors and accountants about fraud detection.

McCormack has taken this learning approach to international accounting conferences in the US, Scotland and to the European Accounting Conference in the Netherlands in 2016.

“As you get more advanced in your career, you can find that flexibility to teach and consult,” she says.

“I also mentor, both formally and informally, the next generation of forensic accountants to come through.”

Master the technical know-how

Forensic accountants also require up-to-date knowledge of software and strong investigative abilities.

Experienced forensic accountant and educator Dr Bernadette McCormack FCPA says financial analysis and audit skills are a must.

“I would also add some level of skill with legal interpretations is necessary,” she says.

“You will need to know, for example, how to read and understand sections of various Acts.”

As forensic accounting is a problem-solving exercise, often involving attempts at concealment and opaque paper trails, you also need to know how to connect the dots, says McCormack.

“You get a bit of information here and there, and you need to be able to make connections.

“So you need good diagnostic skills, not unlike a good doctor. But while people are usually upfront with their GP, there is a layer of concealment with forensic accounting that you’re always trying to uncover.”

When Ferrol is hiring, she looks for technical knowledge of accounting, auditing and investigative accounting, and experience of evidence-gathering.

“I also look for knowledge of various finance-related crimes, such as money laundering, fraud and corporate corruption,” she says.

It’s important to be aware of the relevant accounting standards, primarily the Accounting Professional and Ethical Standards Board’s APES 215: Forensic Accounting Services, which outlines an ethical onus on forensic accountants.

Harris agrees that a fundamental accounting knowledge and awareness of the relevant standards are important.

“When we are involved in a court case, it might be that one person has a certain opinion of how the accounting standards should have been applied and you need to be able to justify your conclusions,” he says.

Harris was also surprised at the amount of report writing involved in forensics, especially in litigation support work.

“Some of the expert reports can run to 100 or so pages, and it’s quite a challenge keeping a logical flow for anyone trying to read and understand it.”

Getting a start in forensic accounting

Entry-level accountants should aim for a solid foundation in audit, to springboard into forensic accounting.

McCormack recommends working in an agency such as the Australian Taxation Office (ATO) or Australian Federal Police to gain audit experience.

“Large organisations often have an internal audit function so, to my mind, that is a place you should also look,” she says.

“Try and do some kind of audit work early on in your career, even if it’s just basiclevel superannuation, to gain those audit skills.”

It is advice McCormack applied in her own life.

For 18 years, she worked as an ATO financial investigator/taxation auditor, then as principal auditor and adviser officer of Queensland Treasury’s Office of State Revenue, and later as chief trust accountant for the Law Society of New South Wales.

“A taxation auditor is a forensic accountant essentially,” says McCormack.

“I started doing standard tax legislation work and was then promoted to compliance, where you do tax audits. An audit background is often a stepping stone into forensic accountant work.”

Ferrol suggests recent graduates gain one to three years of general accounting experience to attain the technical skills in analysing information and the soft skills in communication.

“It’s also advantageous if you can work in an insolvency firm as it will give you exposure to investigative accounting and evidence-gathering work,” she says.

Ferrol also advises recent graduates to seek auditing work in the forensic department of a Big Four accounting firm.

Most of her team, for example, come from one of the Big Four, where they gained that experience in audits and investigations, before moving to forensics.

“Some are also from insolvency firms or other law enforcement agency bodies, such as the ATO, New South Wales Crime Commission or Australian Securities and Investments Commission (ASIC),” she says.

“I’m also looking for someone with passion and who is very confident.”